- Home

- Garden Wildlife

- Arthropods

- Arachnids

- Spiders

Spiders

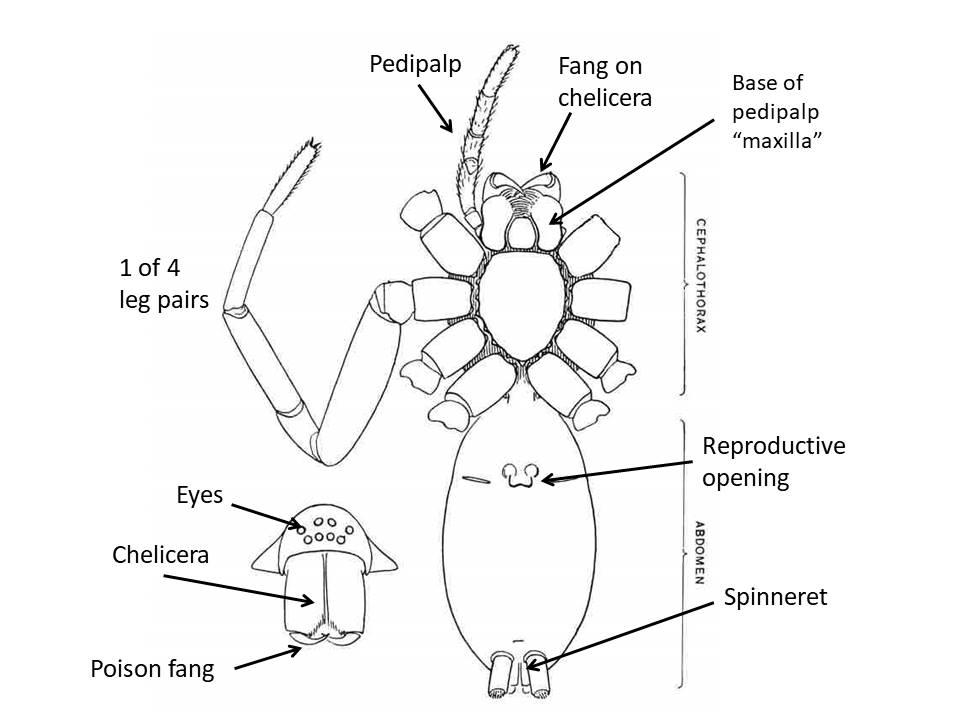

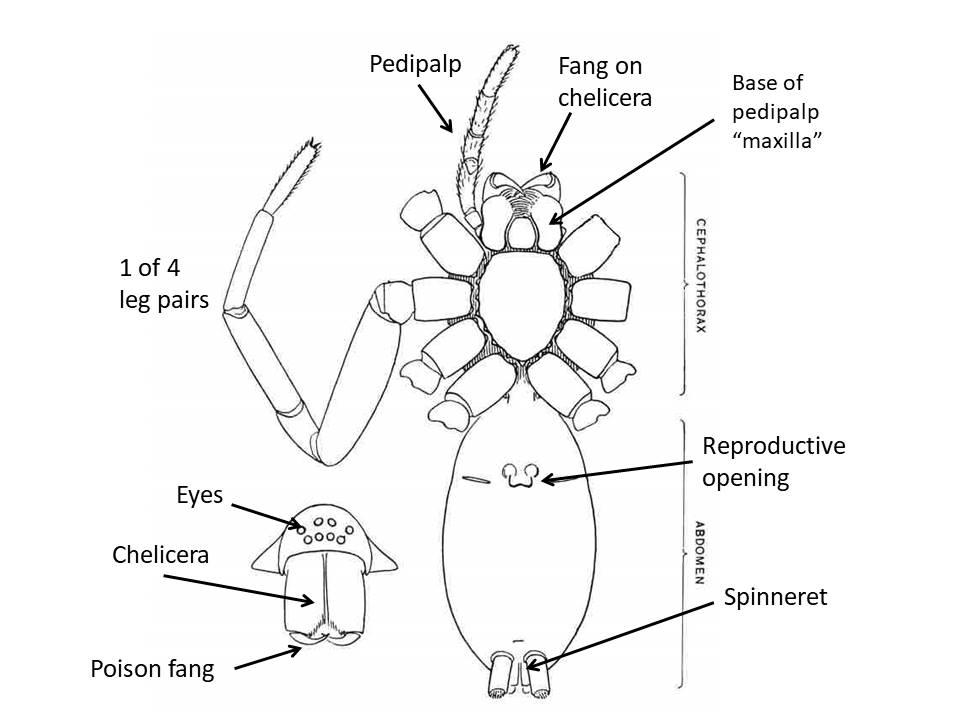

Spiders belong to the order Araneae of the Class Arachnida. They can be differentiated from insects in having four pairs of legs instead of three. They have an abdomen, but the head and thorax are fused together to form a cephalothorax. This means that a spider’s body is in two parts instead of the three distinct parts found in insects or the apparently single part found in the slightly similar harvestmen. They are a very successful group, with over 48,000 described species globally.

Spider have no antennae, but they do have a pair of pedipalps on each side of the head, which are sensory, and also help manipulate food. instead of the complex insect mouthparts, they have a pair of chelicerae, each armed with a poison injecting fang at the tip.

The abdomen holds the reproductive parts, and spinnerets near the anus, which are nozzles for the glands which secrete silk. Spiders have good vision from four pairs of eyes.

Role of spiders in gardens

Spiders are predators that during the spring-autumn period consume a large number of insects and other invertebrate animals. They are therefore generally useful invertebrates to have in the garden. In some parts of the world there are spiders that can inflict painful bites. Fortunately, the spiders of Britain and Ireland are harmless with almost all species being too weak to break human skin. For example the false widow spiders, Steatoda species are sometimes accused of biting people (especialy in the "silly season" when tabloids struggle to fill their pages), but there is very limited evidence to substantiate these claims. If any spider does bite it is unlikely to be worse than a wasp sting. For more information see the false widow spider page of the British Archnological Society.

Species in Britain and Ireland

There are about 650 species of spiders in Britain and Ireland and they occupy a wide range of habitats. Some live in dark corners of garden sheds and buildings, including the common house spiders. Most live out of doors and can be found on plants or running over the soil. Jennifer Owen found 79 species of spiders in her Leicester garden, from 16 families.

Biology

Spiders are predatory animals that subdue their prey by using a pair of fangs to inject it with venom. Most spiders are opportunist predators that feed on a wide range of insects and other invertebrate animals. There are, however, some spiders that specialise in a particular type of prey, such as Dysdera crocata, which feeds on woodlice. All spiders can produce at least four kinds of silk made in internal silk glands, and extruded using abdominal organs known as spinnerets. Even those that do not spin webs will use silk to protect egg masses.

Spiders have a range of strategies for catching their prey. Many produce sticky silk webs, and the spider waits for an insect to fly or walk into the web.

Other spiders do not use webs to catch their prey and rely on active or passive hunting. Wolf spiders, run rapidly over the soil and low-growing plants, relying on speed and their excellent eyesight to capture their prey. Jumping spiders travel in a series of hops and pounce upon their prey.

The crab spiders are ambush predators which sit camouflaged within flowers, and wait motionless for a pollinating insect to arrive. The camouflage can be very effective, making the spider almost invisible until it moves.

To illustrate the species we have two further pages on spiders, on the web-builders and the hunting spiders.

Life cycle

Male spiders are often much smaller than the females and can be very different in appearance. A male approaching a female often runs the risk of being mistaken for a meal and they usually make a slow cautious approach to the female. The eggs are deposited in silk bundles that are placed in the spider's web or may be attached to foliage or hidden under loose bark. Some spiders, such as the wolf spiders, carry their egg sacs between their hind legs. The Nursery web spider, Pisaura mirabilis, initially carries its egg sac but then places it in a large funnel-shaped nursery web spun among plants.

The eggs hatch into spiderlings, which are miniature versions of the adult spiders. The spiderlings of some species, such as Araneus species, remain together in a communal web for a while before dispersing and living separate lives. Lacking wings, spiders cannot disperse as readily as adult insects. Young spiders however can disperse over long distance through a process known as ‘ballooning’. The spider stands with its abdomen pointing upwards and releases strands of silk. When the wind blows, the spider is lifted into the air, with the silk threads acting like a paraglider’s sail. Ballooning spiders have been observed at five kilometres altitude and on ships in mid-ocean. Recent research1. has shown that spiders can detect atmospheric electrostatic charges, and that the force this induces on the silk balloon thread is enough to overcome gravity and take the spiderling up into the air.

Wind-aligned spider threads grounded after a mass ballooning event.

False widow spider photographed in London

Reference:

1. Morley, E.L. and Robert, D. (2018), Current Biology 28, 2324–2330 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2018.05.057

Other sources of information

Website

Web site of the British Arachnological Society

Steven Falk's excellent Araneae photos in many albums

British Spiders Facebook Group

British Spider Identification Facebook Group

Books

Bee, L, Oxford, G and Smith, H. (2020) Britain's Spiders: A Field Guide Second Edition. WILDGuides

Jones, D. (1995). The Country Life Guide to Spiders of Britain and Northern Europe. Country Life Books

Jones-Walters, L.M. (1989) Keys to the families of British spiders. A Field Studies Council AIDGAP key

Roberts, M. J. (2001) Collins Field Guide: Spiders of Britain and Northern Europe. Harper Collins

Roberts, M. J. (1993). The Spiders of Great Britain and Ireland, Compact edition (2 Vols) Harley Books

Page text drafted by Andrew Halstead, reviewed by Andrew Salisbury, compiled by Steve Head

Species in Britain and Ireland

There are about 650 species of spiders in Britain and Ireland and they occupy a wide range of habitats. Some live in dark corners of garden sheds and buildings, including the common house spiders. Most live out of doors and can be found on plants or running over the soil. Jennifer Owen found 79 species of spiders in her Leicester garden, from 16 families.

Biology

Spiders are predatory animals that subdue their prey by using a pair of fangs to inject it with venom. Most spiders are opportunist predators that feed on a wide range of insects and other invertebrate animals. There are, however, some spiders that specialise in a particular type of prey, such as Dysdera crocata, which feeds on woodlice. All spiders can produce at least four kinds of silk made in internal silk glands, and extruded using abdominal organs known as spinnerets. Even those that do not spin webs will use silk to protect egg masses.

Spiders have a range of strategies for catching their prey. Many produce sticky silk webs, and the spider waits for an insect to fly or walk into the web.

Other spiders do not use webs to catch their prey and rely on active or passive hunting. Wolf spiders, run rapidly over the soil and low-growing plants, relying on speed and their excellent eyesight to capture their prey. Jumping spiders travel in a series of hops and pounce upon their prey.

The crab spiders are ambush predators which sit camouflaged within flowers, and wait motionless for a pollinating insect to arrive. The camouflage can be very effective, making the spider almost invisible until it moves.

To illustrate the species we have two further pages on spiders, on the web-builders and the hunting spiders.

Life cycle

Male spiders are often much smaller than the females and can be very different in appearance. A male approaching a female often runs the risk of being mistaken for a meal and they usually make a slow cautious approach to the female. The eggs are deposited in silk bundles that are placed in the spider's web or may be attached to foliage or hidden under loose bark. Some spiders, such as the wolf spiders, carry their egg sacs between their hind legs. The Nursery web spider, Pisaura mirabilis, initially carries its egg sac but then places it in a large funnel-shaped nursery web spun among plants.

The eggs hatch into spiderlings, which are miniature versions of the adult spiders. The spiderlings of some species, such as Araneus species, remain together in a communal web for a while before dispersing and living separate lives. Lacking wings, spiders cannot disperse as readily as adult insects. Young spiders however can disperse over long distance through a process known as ‘ballooning’. The spider stands with its abdomen pointing upwards and releases strands of silk. When the wind blows, the spider is lifted into the air, with the silk threads acting like a paraglider’s sail. Ballooning spiders have been observed at five kilometres altitude and on ships in mid-ocean.

Spiders

Spiders belong to the order Araneae of the Class Arachnida. They can be differentiated from insects in having four pairs of legs instead of three. They have an abdomen, but the head and thorax are fused together to form a cephalothorax. This means that a spider’s body is in two parts instead of the three distinct parts found in insects or the apparently single part found in the slightly similar harvestmen. They are a very successful group, with over 48,000 described species globally.

Spider have no antennae, but they do have a pair of pedipalps on each side of the head, which are sensory, and also help manipulate food. instead of the complex insect mouthparts, they have a pair of chelicerae, each armed with a poison injecting fang at the tip.

The abdomen holds the reproductive parts, and spinnerets near the anus, which are nozzles for the glands which secrete silk. Spiders have good vision from four pairs of eyes.

Species in Britain and Ireland

There are about 650 species of spiders in Britain and Ireland and they occupy a wide range of habitats. Some live in dark corners of garden sheds and buildings, including the common house spiders. Most live out of doors and can be found on plants or running over the soil. Jennifer Owen found 79 species of spiders in her Leicester garden, from 16 families.

Biology

Spiders are predatory animals that subdue their prey by using a pair of fangs to inject it with venom. Most spiders are opportunist predators that feed on a wide range of insects and other invertebrate animals. There are, however, some spiders that specialise in a particular type of prey, such as Dysdera crocata, which feeds on woodlice. All spiders can produce at least four kinds of silk made in internal silk glands, and extruded using abdominal organs known as spinnerets. Even those that do not spin webs will use silk to protect egg masses.

Spiders have a range of strategies for catching their prey. Many produce sticky silk webs, and the spider waits for an insect to fly or walk into the web.

Other spiders do not use webs to catch their prey and rely on active or passive hunting. Wolf spiders, run rapidly over the soil and low-growing plants, relying on speed and their excellent eyesight to capture their prey. Jumping spiders travel in a series of hops and pounce upon their prey.

The crab spiders are ambush predators which sit camouflaged within flowers, and wait motionless for a pollinating insect to arrive. The camouflage can be very effective, making the spider almost invisible until it moves.

To illustrate the species we have two further pages on spiders, on the web-builders and the hunting spiders.

Life cycle

Male spiders are often much smaller than the females and can be very different in appearance. A male approaching a female often runs the risk of being mistaken for a meal and they usually make a slow cautious approach to the female. The eggs are deposited in silk bundles that are placed in the spider's web or may be attached to foliage or hidden under loose bark. Some spiders, such as the wolf spiders, carry their egg sacs between their hind legs. The Nursery web spider, Pisaura mirabilis, initially carries its egg sac but then places it in a large funnel-shaped nursery web spun among plants.

The eggs hatch into spiderlings, which are miniature versions of the adult spiders. The spiderlings of some species, such as Araneus species, remain together in a communal web for a while before dispersing and living separate lives. Lacking wings, spiders cannot disperse as readily as adult insects. Young spiders however can disperse over long distance through a process known as ‘ballooning’. The spider stands with its abdomen pointing upwards and releases strands of silk. When the wind blows, the spider is lifted into the air, with the silk threads acting like a paraglider’s sail. Ballooning spiders have been observed at five kilometres altitude and on ships in mid-ocean. Recent research1. has shown that spiders can detect atmospheric electrostatic charges, and that the force this induces on the silk balloon thread is enough to overcome gravity and take the spiderling up into the air.

Wind-aligned spider threads grounded after a mass ballooning event.

Role of spiders in gardens

Spiders are predators that during the spring-autumn period consume a large number of insects and other invertebrate animals. They are therefore generally useful invertebrates to have in the garden. In some parts of the world there are spiders that can inflict painful bites. Fortunately, the spiders of Britain and Ireland are harmless with almost all species being too weak to break human skin. For example the false widow spiders, Steatoda species are sometimes accused of biting people (especialy in the "silly season" when tabloids struggle to fill their pages), but there is very limited evidence to substantiate these claims. If any spider does bite it is unlikely to be worse than a wasp sting. For more information see the false widow spider page of the British Archnological Society.

False widow spider photographed in London

Reference:

1. Morley, E.L. and Robert, D. (2018), Current Biology 28, 2324–2330 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2018.05.057

Other sources of information

Website

Web site of the British Arachnological Society

Steven Falk's excellent Araneae photos in many albums

British Spiders Facebook Group

British Spider Identification Facebook Group

Books

Bee, L, Oxford, G and Smith, H. (2020) Britain's Spiders: A Field Guide Second Edition. WILDGuides (due September 2020)

Jones, D. (1995). The Country Life Guide to Spiders of Britain and Northern Europe. Country Life Books

Jones-Walters, L.M. (1989) Keys to the families of British spiders. A Field Studies Council AIDGAP key

Roberts, M. J. (2001) Collins Field Guide: Spiders of Britain and Northern Europe. Harper Collins

Roberts, M. J. (1993). The Spiders of Great Britain and Ireland, Compact edition (2 Vols) Harley Books

Page text drafted by Andrew Halstead and reviewed by Andrew Salisbury, compiled by Steve Head