- Home

- Garden Wildlife

- Molluscs

Introduction to molluscs

The phylum Mollusca is one of the most diverse in the animal kingdom, second only to the arthropods in number of species, but with much greater diversity of body plan. There are seven living classes of molluscs and they range from the bivalves (oysters, mussels etc) which are generally immobile with very little central nervous system, to the biggest and most intelligent of invertebrates, the fast moving hunting squids and octopus. The phylum appeared at some time in the early to middle Cambrian period, about 540 million years ago, and because most molluscs have hard calcareous shells they are common and important fossils. There are as many fossil species known as extant ones. Most molluscs are marine, but two groups, the Gastropoda and Bivalvia make it into freshwater, and the gastropods are important on land, as snails and slugs.

Characteristics

Molluscs are "defined" by the a) presence of a calcareous shell (in various forms), b) a sheet of tissue called a mantle, which secretes the shell and encloses a mantle cavity with gills or lungs, c) division of the body into a ventral muscular foot used for locomotion, and a visceral mass protected by the shell d) a special toothed structure called a radula used in feeding. This is a pretty clear set of features, and one could imagine an ancester of all classes looking a bit like a limpet, living on the sea flor and grazing algae. All of these features are either lost or very substantially changed in one or more of the classes. It is sometimes said that if you presented an intelligent 8-year old with the classes of animals, she would probably group the arthropods together because they are so similar, but never the molluscs.

We look at the four larger classes below.

Chitons Class Polyplacophora Chitons have their shell divided into 8 separate plates, which allows them to curl up, and grip very hard with their foot onto rocks. There are about 1,000 species, all marine, and most are intertidal or sub-tidal, a very difficult habitat to which they are uniquely adapted. We have about ten species in Britain and Ireland

Double click to edit

Class Cephalopoda Although there are only about 800 living species of cephalopods, at least 11,000 fossil species are known. The group began in the late Cambrian period about 490m years ago with spirally coiled shells used to provide bouyancy so they could become swimming predators, modifying their foot into tentacles and using their mantle cavity for jet propulsion. They dominated the Ordovician seas, and remained abundant as ammonites and belemnites until almost all were wiped out in the end Cretaceous extinction event 66 million years ago. Only Nautilus (left image) remains of the coiled-shell forms, while belemnite relatives diversified into modern squids and cuttles. The latter include by far the largest and most intelligent invertebrates.

Bivalves Class Bivalvia With about 10,000 living and 12,000 fossil species, this is the second largest group of molluscs. In total contrast to the cephalopods, they have gone in for a quiet, sessile life, burrowed into sediment, or glued onto rocks. Their shell is divided into two plates, left and right over the body, and their very large mantle cavity houses complex gills, used for capturing small particulate food by filter feeding. The foot can be pushed out from the shell allowing burrowing as in cockles, and production of threads to attach the bivalve to the rock as in mussels. They have completely lost the radula, and have done their best to rid themselves of a central nervous system, although they can react to predators by rapidly closing the shell. While most are marine, there are freshwater bivalves which we cover in our page on pond bivalves here.

Snails and slugs Class Gastropoda Snails and their relatives form the largest group of living molluscs, with up to 80,000 species. In some respects they are among the more conservative classes, retaining (initially) all the features of the phylum, although some have lost shell and/or mantle cavity. Basal gastropods all have shells, visceral mass and mantle cavity twisted by 180° anticlockwise, for reasons which remain poorly understood. Gastropods are the only major group other than arthropods and vertebrates to have made success of life out of the soil on land. The majority of land snails and slugs are "pulmonates" and have converted the gill-bearing mantle cavity into a lung. Land slugs have evolved more than once from snails through secondary shell reduction.

Gastropod biology

We are covering the molluscs (which in gardens essentially means the gastropods) in some detail here, because they are a bit of a Cinderella group and not given much detail in garden guides - especially the aquatic species.

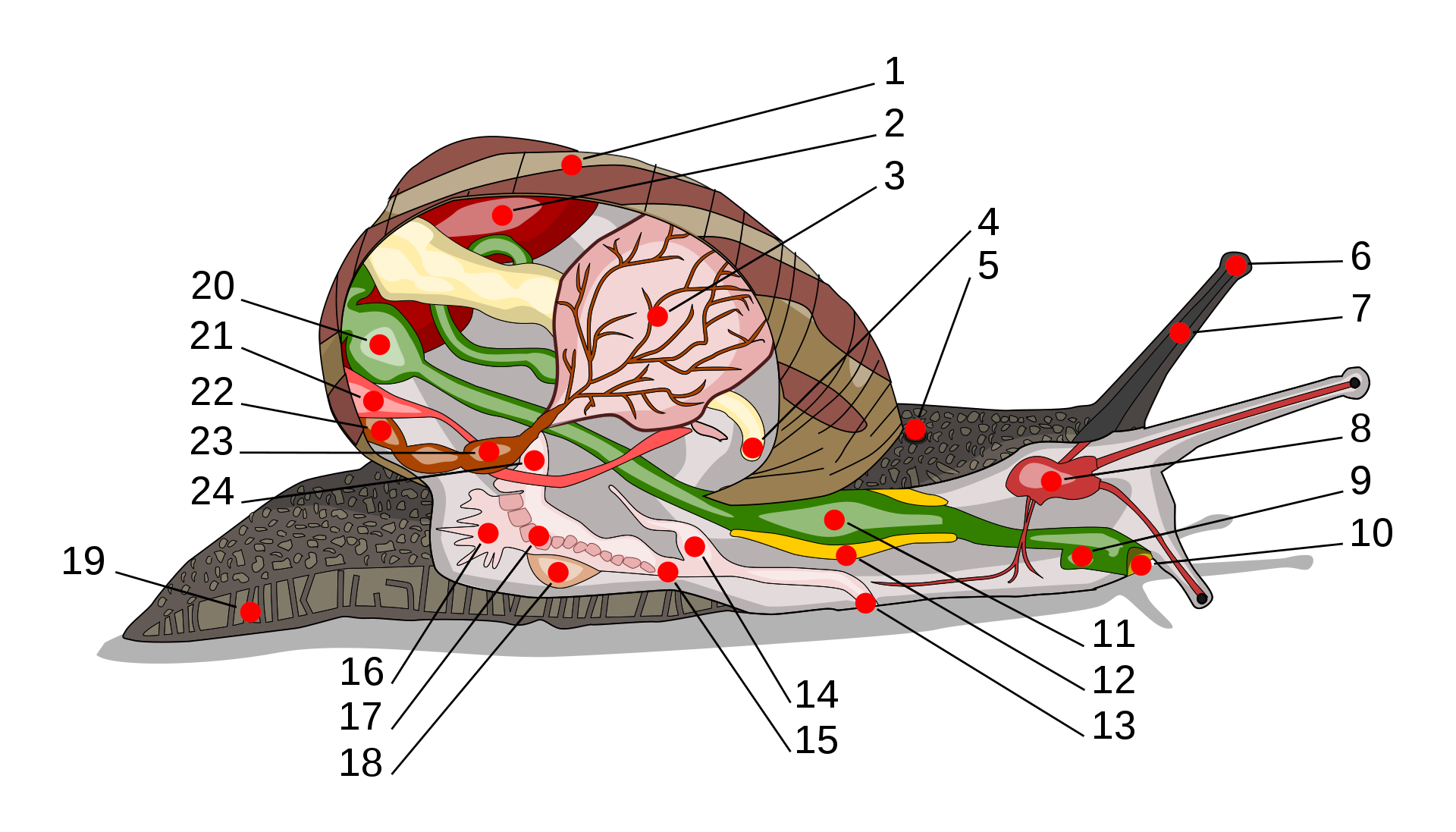

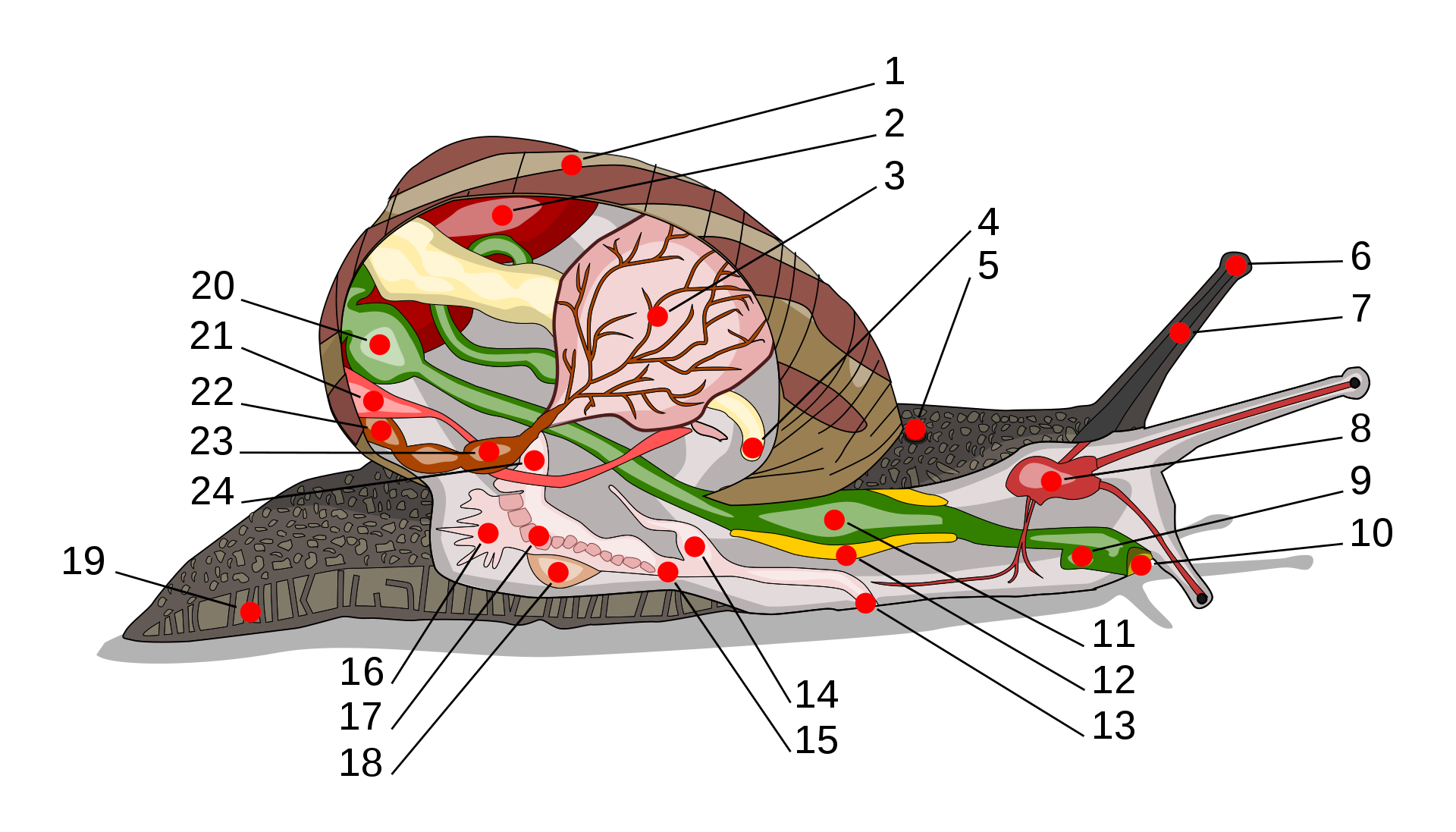

The diagram above shows just how complicated and sophisticated the anatomy of a pulmonate snail can be, and the dissection of one is extremely interesting. They have well formed organ systems in parallel to our own. Their nervous system is sophisticated, with a large brain (cerebral gangla) in the head under the tentacles. The main tentacles carry eyes at their tips, the lower ones are touch and chemical sensors. Th inner mantle cavity forms a lung amply served by blood vessels conected to a heart which pump oxygenated blood to the rest of the body. Unlike aquatic molluscs which excrete waste nitrogen material as ammonia, land snails excrete it as urea (like us) which wastes far less water.

Feeding

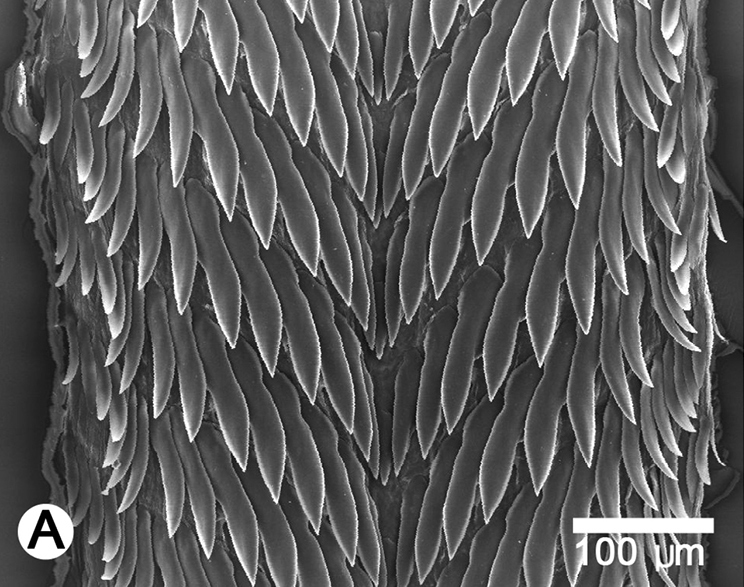

Most marine gastropods are carnivores, but most land snails and slugs are herbivores, either eating fresh plant material (which makes some a real nuisance in the garden) or more commonly, decaying plant material and detritus. They use their radula which is like a flexible file with chitinous teeth often hardened by mineral such as calcite. With its accompanying apparatus it rasps away at food, grating off small particles which pass into the stomach and gut and are processed in the liver.

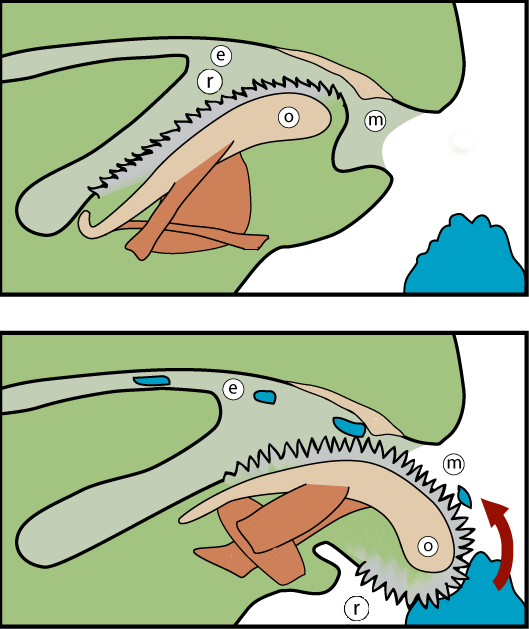

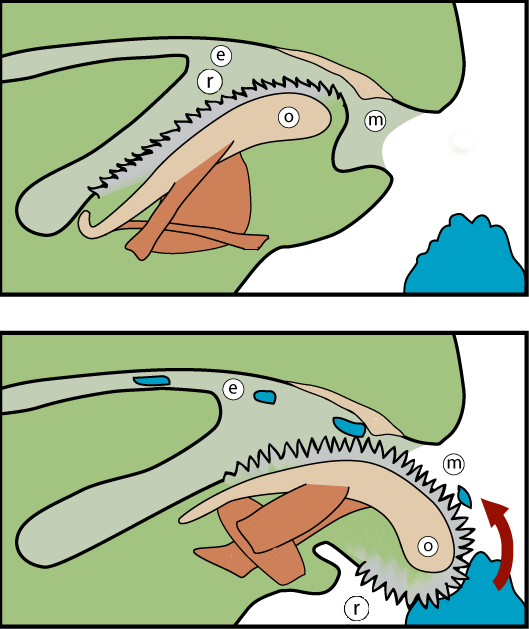

How the radula works The radula (r) is supported by a cartilaginous structure called the odontophore (o) which works like a tongue that can be pushed out of the mouth (m) by some of the muscles shown in brown. In the second picture the radula is rubbed over the food (blue - perhaps it's a slug pellet!), breaking off particles which are brought into the oesophagus (e) by the licking motion.

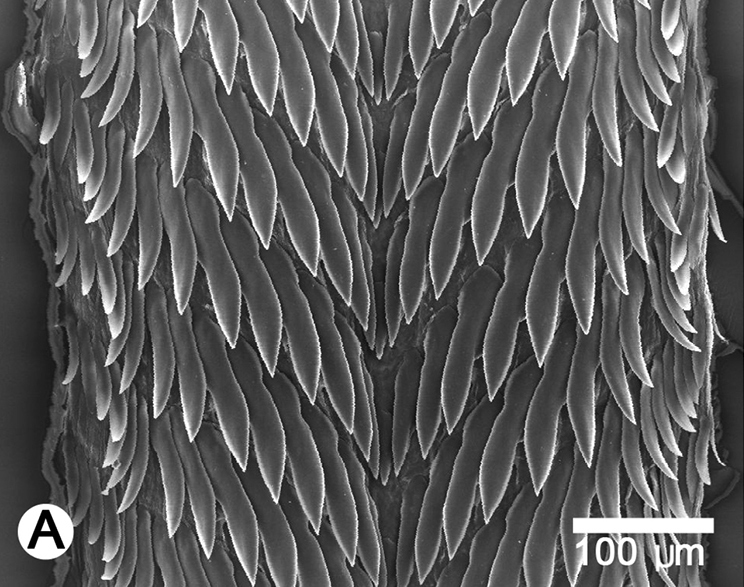

Below: radula of a land snail showing teeth rows, and (right) resulting scrape marks on an algal-covered stone. It's an effective process, and there isn't much food missed.

Life history

Snails and slugs are simultaneous hermaphrodites, which means the have functional female and male parts at the same time. This means every mature snail they meet is a potential partner, and the exchange of sperm is a mutual affair. The two wind around each other, with much covering of mucus, and in the case of the great grey or leopard slug Limax maximus the two partners hang down from a twig on a thick mucus thread. If that isn't bizarre enough, in some species sperm exchange seems to be triggered by the thrusting of a substantial calcareous weapon called a "love dart" through the partner's body wall. These darts are secreted in a pouch or sac opening off the female part of the genital apparatus.

Left: Leopard slugs Limax maximus mating. See also this amazing Youtube video which should make everyone jealous of slugs. Right: love dart embeded in one partner of a pair of common garden snails - which should put almost everyone right off being a snail.

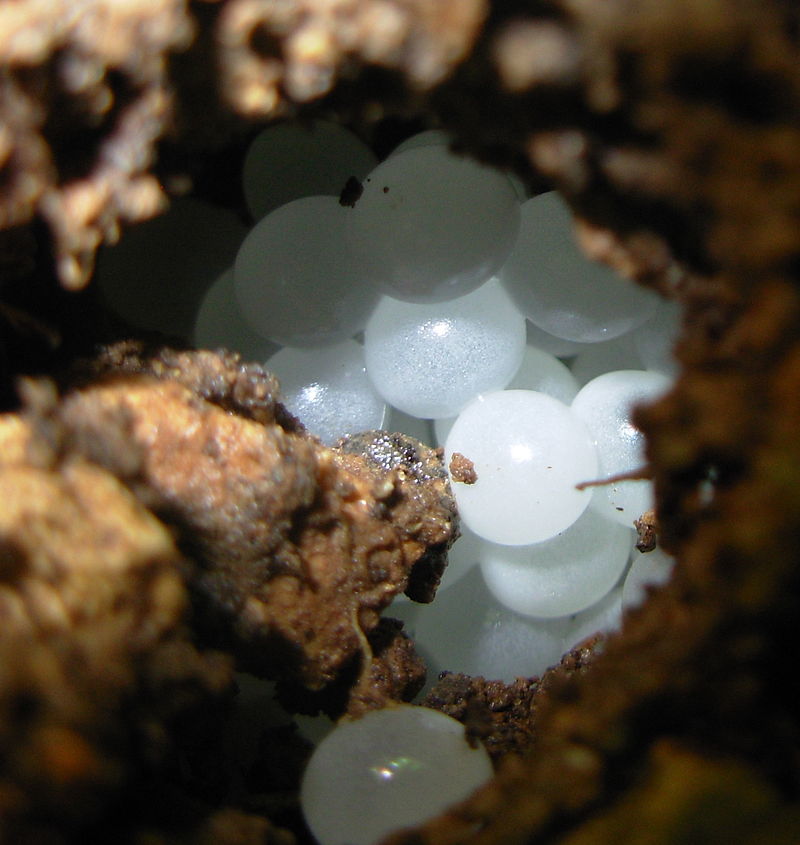

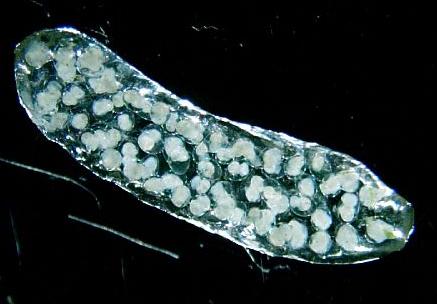

Slugs and snails lay large yolky eggs after mating, buried in moist ground in the case of land snails and slugs, or glued to vegetation in pond snails. There is no larval stage, and miniature snails hatch out and grow progressively to maturity, usually within a year. Adult common garden snails can live for 3-5 years.

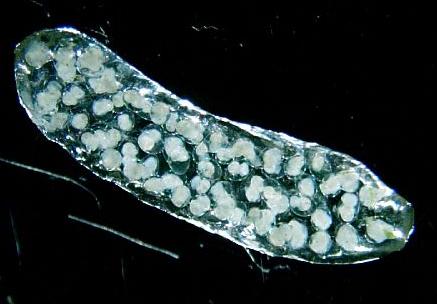

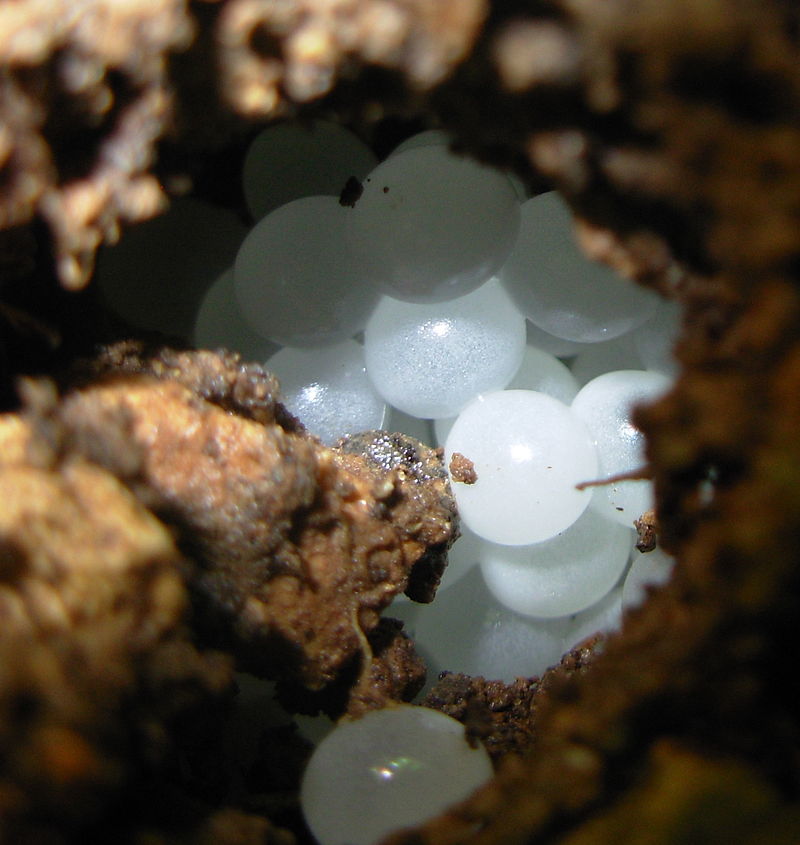

Left: eggs of the common garden snail Cornu aspersum Right: Egg mass laid by pond snail Lymnaea stagnalis

Snail eggs are harvested and sold to extremely wealthy gourmets as snail caviar, with a current UK price of £1.00 per gram, high, but certainly cheaper than the real thing.

Overall, we want you to know that garden molluscs are a pretty interesting lot, and deserve more sympathy and study. It is a subject where amateurs can make a serious discovery, as when Ruth Brooks experimented on the homing ability of garden snails leading to further publications1,2.

References

1. Brooks, R. (2013) A Slow Passion: Snails, my Garden, and Me London:

Bloomsbury

2. Dunstan, D.J . and Hodgson, D. J. (2014) Snails home. Phys. Scr. 89:1:10

Other sources of information

Website

Books

Barker, G.M. (ed) (2001) The Biology of Terrestrial Molluscs CABI Publishing

Cameron, R. (2016) Slugs and Snails. New Naturalist Series Harper Collins London

Cameron, R. & Riley, G. (2008) Land snails in the British Isles. A Field Studies Council AIDGAP key

Page written and compiled by Steve Head

Introduction to molluscs

The phylum Mollusca is one of the most diverse in the animal kingdom, second only to the arthropods in number of species, but with much greater diversity of body plan. There are seven living classes of molluscs and they range from the bivalves (oysters, mussels etc) which are generally immobile with very little central nervous system, to the biggest and most intelligent of invertebrates, the fast moving hunting squids and octopus. The phylum appeared at some time in the early to middle Cambrian period, about 540 million years ago, and because most molluscs have hard calcareous shells they are common and important fossils. There are as many fossil species known as extant ones. Most molluscs are marine, but two groups, the Gastropoda and Bivalvia make it into freshwater, and the gastropods are important on land, as snails and slugs.

Characteristics

Molluscs are "defined" by the a) presence of a calcareous shell (in various forms), b) a sheet of tissue called a mantle, which secretes the shell and encloses a mantle cavity with gills or lungs, c) division of the body into a ventral muscular foot used for locomotion, and a visceral mass protected by the shell d) a special toothed structure called a radula used in feeding. This is a pretty clear set of features, and one could imagine an ancester of all classes looking a bit like a limpet, living on the sea flor and grazing algae. All of these features are either lost or very substantially changed in one or more of the classes. It is sometimes said that if you presented an intelligent 8-year old with the classes of animals, she would probably group the arthropods together because they are so similar, but never the molluscs.

We look at the four larger classes below.

Chitons Class Polyplacophora Chitons have their shell divided into 8 separate plates, which allows them to curl up, and grip very hard with their foot onto rocks. There are about 1,000 species, all marine, and most are intertidal or sub-tidal, a very difficult habitat, to which they are uniquely adapted. We have about ten species in Britain and Ireland.

Chiton

Class Cephalopoda Although there are only about 800 living species of cephalopods, at least 11,000 fossil species are known. The group began in the late Cambrian period about 490m years ago with spirally coiled shells used to provide bouyancy so they could become swimming predators, modifying their foot into tentacles and using their mantle cavity for jet propulsion. They dominated the Ordovician seas, and remained abundant as ammonites and belemnites until almost all were wiped out in the end Cretaceous extinction event 66 million years ago. Only Nautilus remains of the coiled-shell forms, while belemnite relatives diversified into modern squids and cuttles. These include by far the largest and most intelligent of all invertebrates.

Nautilus Squid

Bivalves Class Bivalvia With about 10,000 living and 12,000 fossil species, this is the second largest group of molluscs. In total contrast to the cephalopods, they have gone in for a quiet, sessile life, burrowed into sediment, or glued onto rocks. Their shell is divided into two plates, left and right over the body, and their very large mantle cavity houses complex gills, used for capturing small particulate food by filter feeding. The foot can be pushed out from the shell allowing burrowing as in cockles, and production of threads to attach the bivalve to the rock as in mussels. They have completely lost the radula, and have done their best to rid themselves of a central nervous system, although they can react to predators by rapidly closing the shell. While most are marine, there are freshwater bivalves which we cover in our page on pond bivalves here.

Bivalve - blue mussel shell

Snails and slugs Class Gastropoda Snails and their relatives form the largest group of living molluscs, with up to 80,000 species. In some respects they are among the more conservative classes, retaining (initially) all the features of the phylum, although some have lost shell and/or mantle cavity. Basal gastropods all have shells, visceral mass and mantle cavity twisted by 180° anticlockwise, for reasons which remain poorly understood. Gastropods are the only major group other than arthropods and vertebrates to have made success of life out of the soil on land. The majority of land snails and slugs are "pulmonates" and have converted the gill-bearing mantle cavity into a lung. Land slugs have evolved more than once from snails through secondary shell reduction.

Typical gastropod - garden snail

Gastropod biology

We are covering the molluscs (which in gardens essentially means the gastropods) in some detail here, because they are a bit of a Cinderella group and not covered in much detail in garden guides - especially the aquatic species.

The diagram above shows just how complicated and sophisticated the anatomy of a pulmonate snail can be, and the dissection of one is extremely interesting. They have well formed organ systems in parallel to our own. Their nervous system is sophisticated, with a large brain (cerebral gangla) in the head under the tentacles. The main tentacles carry eyes at their tips, the lower ones are touch and chemical sensors. The inner mantle cavity forms a lung amply served by blood vessels conected to a heart which pump oxygenated blood to the rest of the body. Unlike aquatic molluscs which excrete waste nitrogen material as ammonia, land snails excrete it as urea (like us) which wastes far less water.

Feeding

Most marine gastropods are carnivores, but most land snails and slugs are herbivores, either eating fresh plant material (which makes some a real nuisance in the garden) or more commonly, decaying plant material and detritus. They use their radula which is like a flexible file with chitinous teeth often hardened by mineral such as calcite. With its accompanying apparatus it rasps away at food, grating off small particles which pass into the stomach and gut and are processed in the liver.

How the radula works The radula (r) is supported by a cartilaginous structure called the odontophore (o) which works like a tongue that can be pushed out of the mouth (m) by some of the muscles shown in brown. In the second picture the radula is rubbed over the food (blue - perhaps it's a slug pellet!), breaking off particles which are brought into the oesophagus (e) by the licking motion.

Above: radula of a land snail showing teeth rows, and (right) resulting scrape marks on an algal-covered stone. It's an effective process, and there isn't much food missed.

Life history

Snails and slugs are simultaneous hermaphrodites, which means the have functional female and male parts at the same time. This means every mature snail you meet is a potential partner, and the exchange of sperm is a mutual affair. The two wind around each other, with much covering of mucus, and in the case of the great grey or leopard slug Limax maximus the two partners hang down from a twig on a thick mucus thread. If that isn't bizarre enough, in some species sperm exchange seems to be triggered by the thrusting of a substantial calcareous weapon called a "love dart" through the partner's body wall. These darts are secreted in a pouch or sac opening off the female part of the genital apparatus.

Left: eggs of the common garden snail Cornu aspersum Right: Egg mass laid by pond snail Lymnaea stagnalis

Snail eggs are harvested and sold to extremely wealthy gourmets as snail caviar, with a current UK price of £1.00 per gram, high, but certainly cheaper than the real thing.

Overall, we want you to know that garden molluscs are a pretty interesting lot, and deserve more sympathy and study. It is a subject where amateurs can make a serious discovery, as when Ruth Brooks experimented on the homing ability of garden snails leading to further publications1,2.

References

1. Brooks, R. (2013) A Slow Passion: Snails, my Garden, and Me London: Bloomsbury

2. Dunstan, D.J . and Hodgson, D. J. (2014) Snails home. Phys. Scr. 89:1:10

Other sources of information

Website

Website of the Conchological Society of Great Britain and Ireland.

Books

Barker, G.M. (ed) (2001) The Biology of Terrestrial Molluscs CABI Publishing

Cameron, R. (2016) Slugs and Snails. New Naturalist Series Harper Collins London

Cameron, R. & Riley, G. (2008) Land snails in the British Isles. A Field Studies Council AIDGAP key

Page written and compiled by Steve Head

Left: Leopard slugs Limax maximus mating See also this amazing Youtube video which should make everyone jealous of slugs. Right: love dart embeded in one partner of a pair of common garden snails - which should put almost everyone right off being a snail.

Slugs and snails lay large yolky eggs after mating, buried in moist ground in the case of land snails and slugs, or glued to vegetation in pond snails. There is no larval stage, and miniature snails hatch out and grow progressively to maturity, usually within a year. Adult common garden snails can live for 3-5 years.