- Home

- Garden Wildlife

- Insects

- Lepidoptera

Lepidoptera: Introduction

The order Lepidoptera comprises the moths and butterflies, one of the largest insect Orders, with 180,000 species worldwide. There are approximately 2,560 species in Britain and Ireland, including some that migrate annually to Britain but do not normally overwinter here. Moths and butterflies are characterised by having wings that are covered by many overlapping scales. It is the arrangement of these scales that give moth and butterfly wings the distinctive colour patterns that are usually enough to identify the species. There is a wide variation in size in the Lepidoptera; the smallest leaf-mining moths have a wing span of less than 4mm, while the largest hawk moths can have a wing span of more than 100mm.

![Moth antennae. Cropped from: Photo by David Short from Windsor, UK [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)]](images/1280px-Peppered_moth_(sw)_(15197082342).jpg)

The Lepidoptera are conventionally divided by naturalists into butterflies, macromoths (larger) and (smaller) micromoths.

There is no single characteristic that can be used to separate butterflies from moths. All (British and Irish) butterflies are day-flying insects, as are some moths, and all (British and Irish) butterflies have clubbed antennae. Most moths have either wire-like antennae, or feathery ones (especially in the males) for detecting pheromones released by potential partners. Just to be inconvenient, day flying Burnet moths have somewhat clubbed antennae.

When at rest, most butterflies hold their wings vertically above their bodies, whereas many moths hold their wings out flat, or folded along the body. Some skipper butterflies hold their wings in a peculiar way.

.jpg)

Above: Clubbed butterfly antennae Wire-like moth antennae

Below: Feathered moth antennae Club-like antennae on burnet moth

Butterflies and moths also differ in the way they link their fore and hind wings together for efficient flight.

There is really little problem in telling butterflies from moths in Britain and Ireland. We only have 59 butterfly species, of which only 17 are likely to occur in gardens, and these are very easily learnt and memorised.

The division between macromoths and micromoths is blurred and not "natural". Whilst most macromoths are larger than micromoths, some micromoths are larger than some macromoths. For many years, the standard book used by lepidopterists for identifying the larger moths was Richard South’s The Moths of the British Isles, first published in 1907. The moth families covered in that two volume book have become the macromoths, with all the other families consigned to the micromoths.

Because there are so many excellent websites and books on identifying British and Irish Lepidoptera, we do not cover them very extensively here, beyond a brief introduction to the main families. Instead we focus more ecologically, on the life style of the moths, according to how their larvae feed, and the adult habits.

- Butterflies

- Introduction to moths

- Moths with solitary larvae

- Moths with gregarious larvae

- Moths with fruit and seed-eating larvae

- Moths with stem-boring larvae

- Moths with root-eating larvae

- Moths with leaf-mining larvae

- Day flying moths

Butterflies and moths undergo complete metamorphosis as they pass through the egg, caterpillar or larval stages, the chrysalis or pupal stage before reaching the adult stage. The larval stages are herbivores feeding on the foliage or other parts of plants. Some adult moths do not feed but those that feed suck nectar from flowers, as do butterflies. Some species will also take liquids from rotting fruit, muddy water and even rotting animal carcasses. Many butterfly species have a long ‘tongue’ or proboscis that is rolled up under the head when the insect is not feeding.

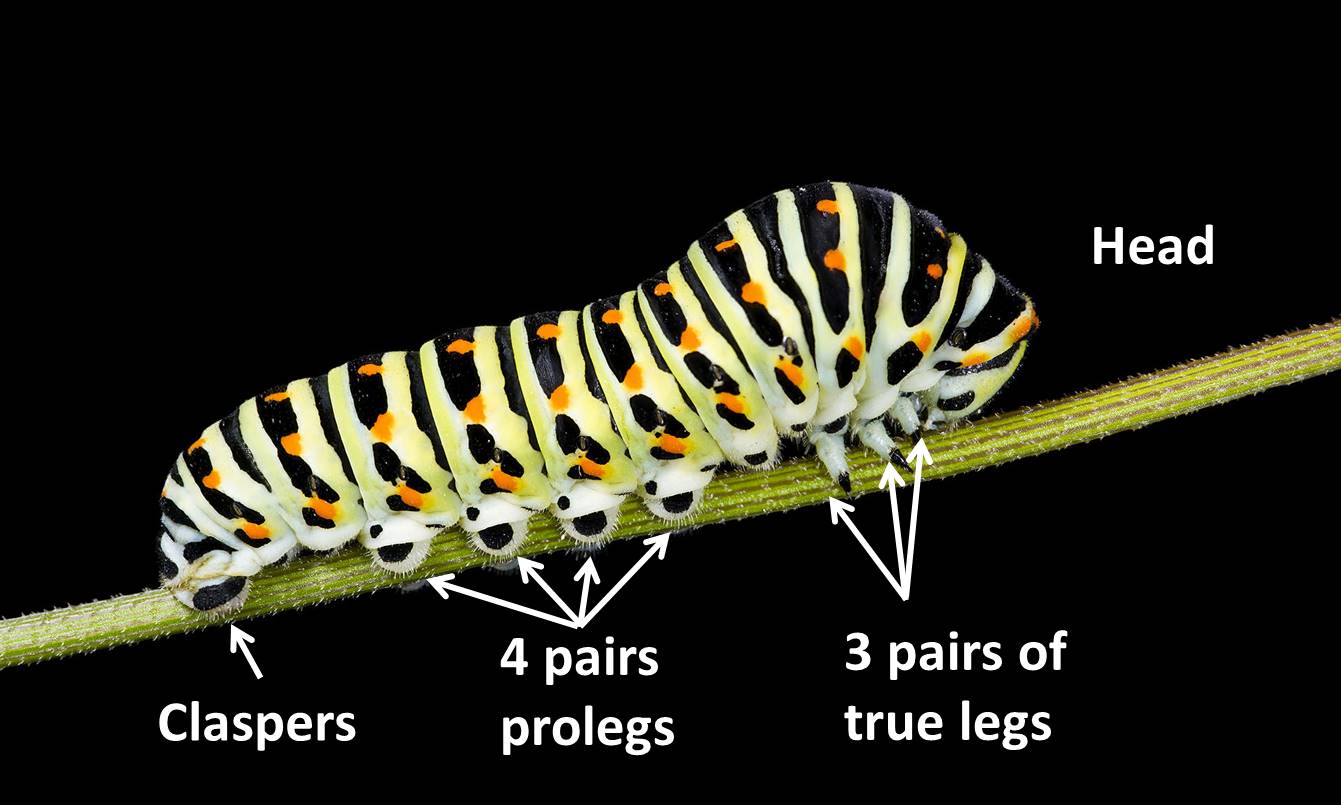

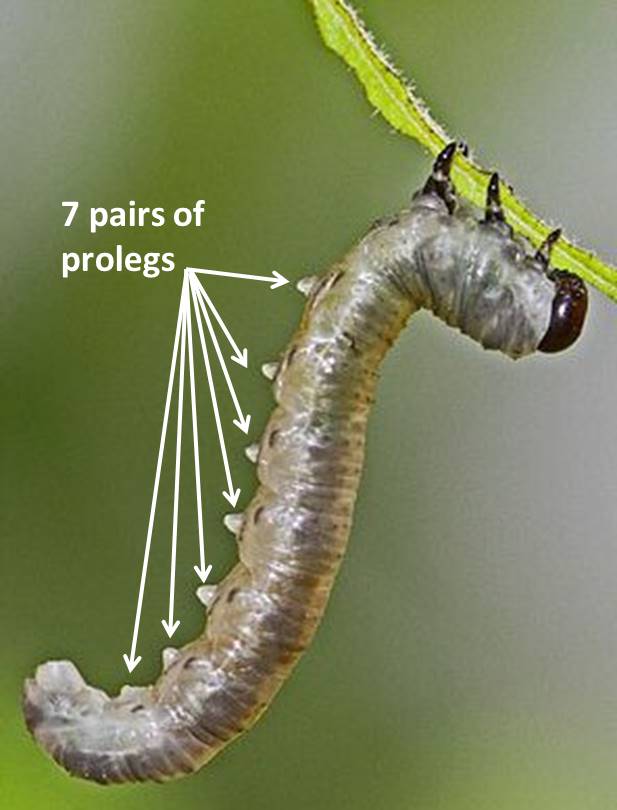

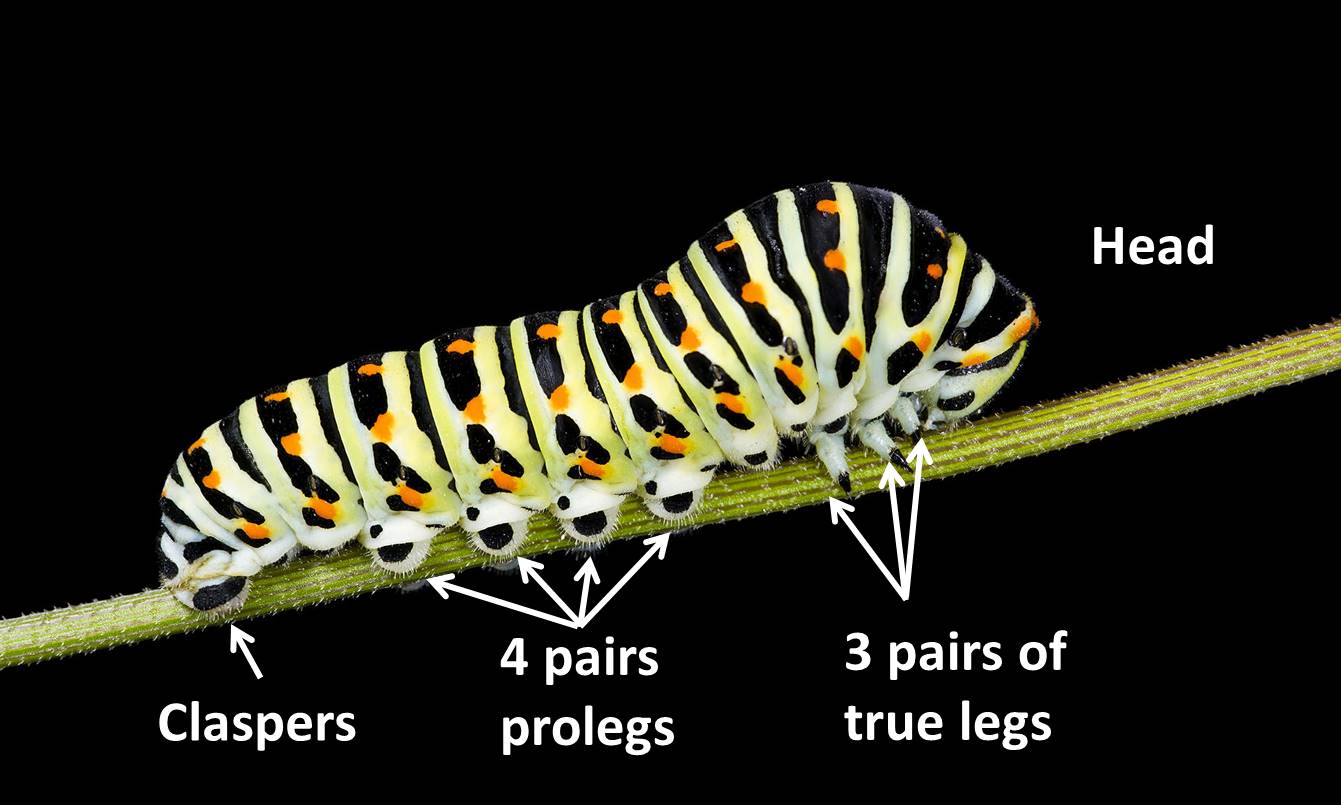

Lepidopteran larvae are called caterpillars, and are quite easy to recognise. They have 3 pairs of true legs (corresponding to the 3 pairs of the adult) behind their head, and up to 5 pairs of "prolegs" with hooks at the rear of the body, and a pair of claspers on the last segment. Many have defensive hairs or other structures.

_female.jpg)

.jpg)

Above: Typical butterfly resting position Small skipper Thymelicus sylvestris resting

Below: Typical spread-wing resting posture for moths Contrasting folded wings-to-body pattern

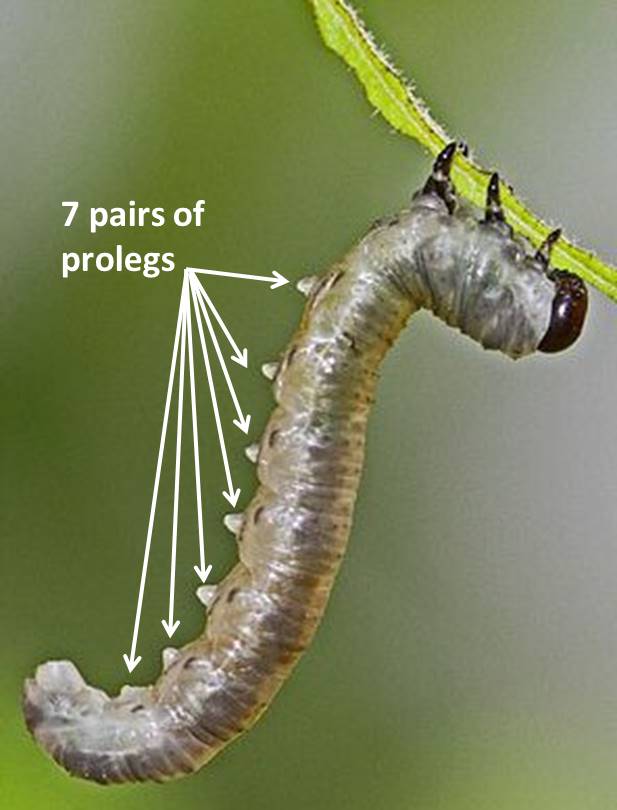

Sawfly larvae (above right) often closely resemble lepidopteran caterpillars, but have many more pairs of prolegs.

Analysis of the considerable available data on lepidoptera sightings has shown that some species have increased in numbers and distribution over the last 30 years. However the number of species of butterflies and moths that have declined over that period is greater than those that have increased. Habitat loss (land use change) and fragmentation of suitable habitat are important contributory causes in this loss, although climate change is now having some effect, especially on north-south distribution patterns.

Other sources of information

Website

Web site of Butterfly Conservation

State of Britains' Butterflies report

The State of Britain’s larger moths report

Website of UK Moths

Website of National Moth Night

Website of UK Butterflies

Books

Fox, R., Asher, J., Brereton, T., Roy, D. & Warren, M. (2006) The state of butterflies in Britain and Ireland. Pisces Books

Goater, B. (1986) British Pyralid Moths. Harley Books

Hart, C. (2011) British Plume Moths. British Entomological and Natural History Society

May, P. (editor) (2014) A Handbook for Lepidopterists. Amateur Entomologists’ Society

Newland, D., Still, R. & Swash, A. (2019) Britain’s Day-flying Moths. WildGuides Ltd 2nd edition

Newland, D., Still, R., Tomlinson, D. & Swash, A. (2010) Britain’s Butterflies. WildGuides Ltd

Porter, J. (2010) Colour Identification Guide to the Caterpillars of the British Isles. Apollo Books

Skinner, B. (2009) Colour Identification Guide to the Moths of the British Isles. Apollo Books

Sterling, P. & Parsons, M. (2012) Field Guide to the Micro-moths of Great Britain and Ireland. British Wildlife Publications

Sterling, P., Henwood, B., Lewington, R. (2020) Field Guide to the Caterpillars of Great Britain and Ireland

Bloomsbury Wildlife Guides

Townsend, M. & Waring, P. (2007) Concise Guide to the Moths of Great Britain and Ireland. British Wildlife Publications

Page drafted by Andrew Halstead, reviewed by Andrew Salisbury, edited by Steve Head

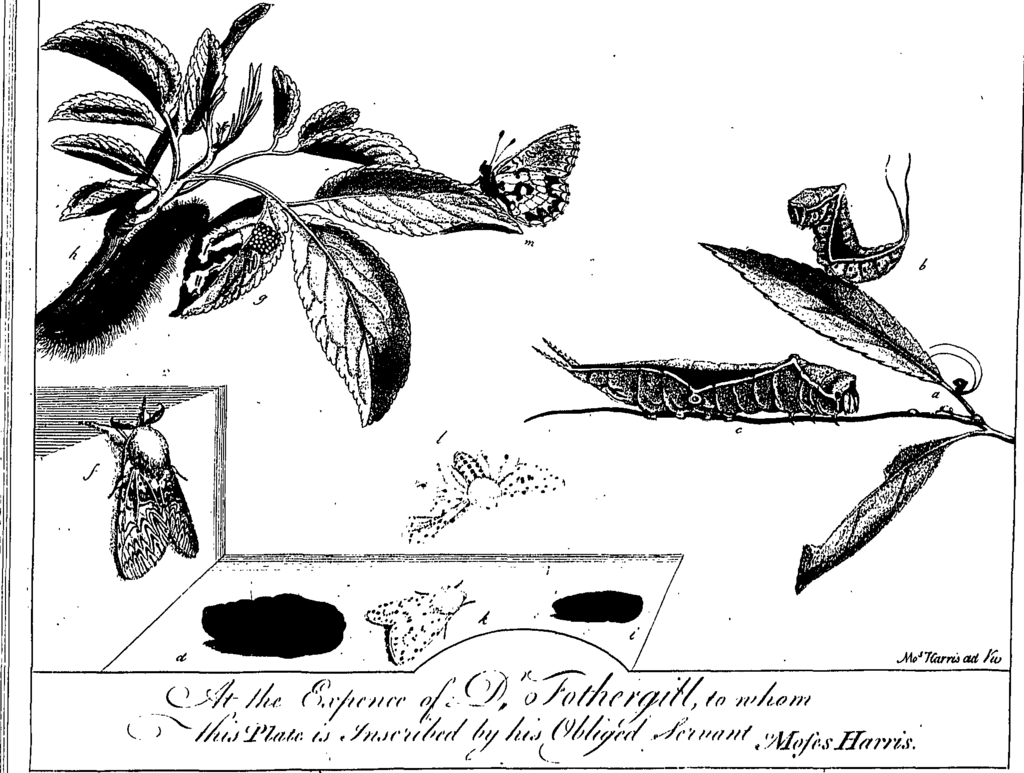

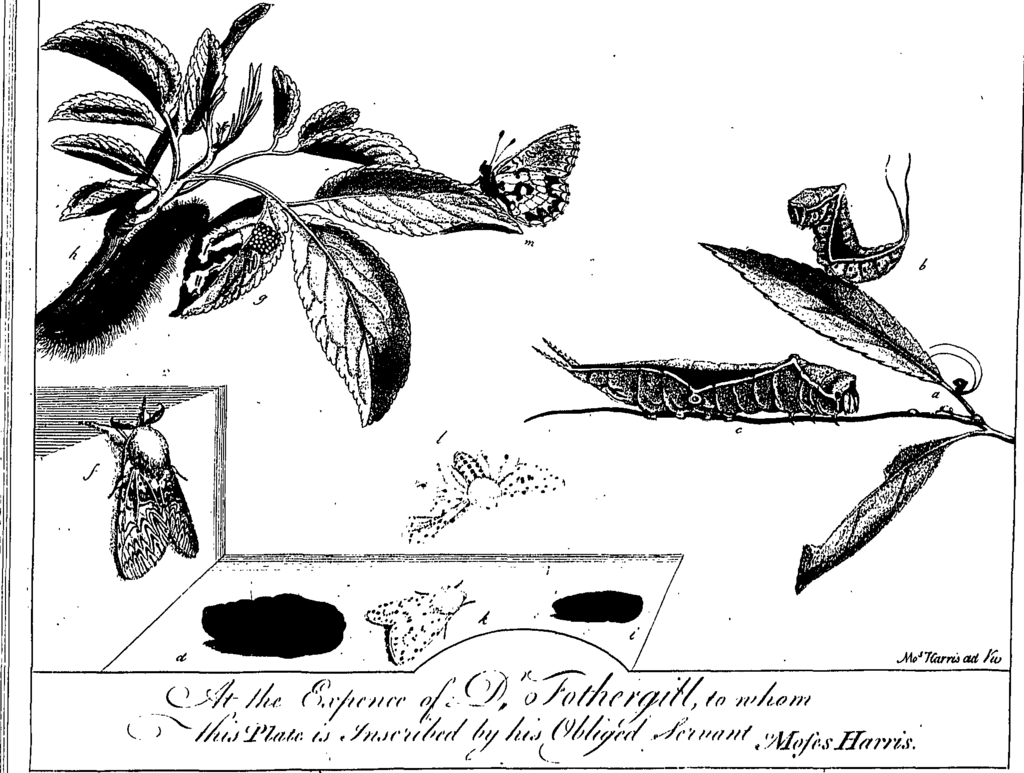

Left: Moses Harris

Right: plate from The Aurelian showing puss moth Cerura vinula, larvae and adult (bottom left)

Lepidoptera: Introduction

The order Lepidoptera comprises the moths and butterflies, one of the largest insect Orders, with 180,000 species worldwide. There are approximately 2,560 species in Britain and Ireland, including some that migrate annually to Britain but do not normally overwinter here. Moths and butterflies are characterised by having wings that are covered by many overlapping scales. It is the arrangement of these scales that give moth and butterfly wings the distinctive colour patterns that are usually enough to identify the species. There is a wide variation in size in the Lepidoptera; the smallest leaf-mining moths have a wing span of less than 4mm, while the largest hawk moths can have a wing span of more than 100mm.

Left: Moses Harris

Right: plate from The Aurelian showing puss moth Cerura vinula, larvae and adult (bottom left)

The Lepidoptera are conventionally divided by naturalists into butterflies, macromoths (larger) and (smaller) micromoths.

There is no single characteristic that can be used to separate butterflies from moths. All (British and Irish) butterflies are day-flying insects, as are some moths, and all (British and Irish) butterflies have clubbed antennae. Most moths have either wire-like antennae, or feathery ones (especially in the males) for detecting pheromones released by potential partners. Just to be inconvenient, day flying Burnet moths have somewhat clubbed antennae.

Above: Clubbed butterfly antennae Wire-like moth antennae

Below: Feathered moth antennae Club-like antennae on burnet moth

![Moth antennae. Cropped from: Photo by David Short from Windsor, UK [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)]](images/1280px-Peppered_moth_(sw)_(15197082342).jpg)

.jpg)

When at rest, most butterflies hold their wings vertically above their bodies, whereas many moths hold their wings out flat, or folded along the body. Some skipper butterflies hold their wings in a peculiar way.

Above: Typical butterfly resting position Small skipper Thymelicus sylvestris

resting

Below:Typical spread-wing resting Contrasting folded wings-to-body pattern

posture for moths

_female.jpg)

Butterflies and moths also differ in the way they link their fore and hind wings together for efficient flight.

There is really little problem in telling butterflies from moths in Britain and Ireland. We only have 59 butterfly species, of which only 17 are likely to occur in gardens, and these are very easily learnt and memorised.

The division between macromoths and micromoths is blurred and not "natural". Whilst most macromoths are larger than micromoths, some micromoths are larger than some macromoths. For many years, the standard book used by lepidopterists for identifying the larger moths was Richard South’s The Moths of the British Isles, first published in 1907. The moth families covered in that two volume book have become the macromoths, with all the other families consigned to the micromoths.

Because there are so many excellent websites and books on identifying British and Irish Lepidoptera, we do not cover them very extensively here, beyond a brief introduction to the main families. Instead we focus more ecologically, on the life style of the moths, according to how their larvae feed, and the adult habits.

- Butterflies

- Introduction to moths

- Moths with solitary larvae

- Moths with gregarious larvae

- Moths with fruit and seed-eating larvae

- Moths with stem-boring larvae

- Moths with root-eating larvae

- Moths with leaf-mining larvae

- Day flying moths

Butterflies and moths undergo complete metamorphosis as they pass through the egg, caterpillar or larval stages, the chrysalis or pupal stage before reaching the adult stage. The larval stages are herbivores feeding on the foliage or other parts of plants. Some adult moths do not feed but those that feed suck nectar from flowers, as do butterflies. Some species will also take liquids from rotting fruit, muddy water and even rotting animal carcasses. Many butterfly species have a long ‘tongue’ or proboscis that is rolled up under the head when the insect is not feeding.

Lepidopteran larvae are called caterpillars, and are quite easy to recognise. They have 3 pairs of true legs (corresponding to the 3 pairs of the adult) behind their head, and up to 5 pairs of "prolegs" with hooks at the rear of the body, and a pair of claspers on the last segment. Many have defensive hairs or other structures.

.jpg)

Sawfly larvae (above right) often closely resemble lepidopteran caterpillars, but have many more pairs of prolegs.

Analysis of the considerable available data on lepidoptera sightings has shown that some species have increased in numbers and distribution over the last 30 years. However the number of species of butterflies and moths that have declined over that period is greater than those that have increased. Habitat loss (land use change) and fragmentation of suitable habitat are important contributory causes in this loss, although climate change is now having some effect, especially on north-south distribution patterns.

Other sources of information

Websites

Web site of Butterfly Conservation

State of Britains' Butterflies report

The State of Britain’s larger moths report

Website of UK Moths

Website of National Moth Night

Website of UK Butterflies

Books

Fox, R., Asher, J., Brereton, T., Roy, D. & Warren, M. (2006) The state of butterflies in Britain and Ireland. Pisces Books

Goater, B. (1986) British Pyralid Moths. Harley Books

Hart, C. (2011) British Plume Moths. British Entomological and Natural History Society

May, P. (editor) (2014) A Handbook for Lepidopterists. Amateur Entomologists’ Society

Newland, D., Still, R. & Swash, A. (2019) Britain’s Day-flying Moths. WildGuides Ltd 2nd edition

Newland, D., Still, R., Tomlinson, D. & Swash, A. (2010) Britain’s Butterflies. WildGuides Ltd

Porter, J. (2010) Colour Identification Guide to the Caterpillars of the British Isles. Apollo Books

Skinner, B. (2009) Colour Identification Guide to the Moths of the British Isles. Apollo Books

Sterling, P. & Parsons, M. (2012) Field Guide to the Micro-moths of Great Britain and Ireland. British Wildlife Publications

Sterling, P., Henwood, B., Lewington, R. (2020) Field Guide to the Caterpillars of Great Britain and Ireland

Bloomsbury Wildlife Guides

Townsend, M. & Waring, P. (2007) Concise Guide to the Moths of Great Britain and Ireland. British Wildlife Publications

Page drafted by Andrew Halstead, reviewed by Andrew Salisbury, edited by Steve Head

Moths and butterflies are the most popular and widely studied group of insects in the British Isles. The first significant book on them was Moses Harris's "The Aurelian Or Natural History Of English Insects; Namely, Moths And Butterflies. Together With The Plants On Which They Feed" published in 1776. The 19th and early 20th century craze for collecting butterflies (and their varieties) was partly responsible for the local extinction of a few species.

Highly magnified view of a moth wing showing the very distinctive scales. The term "Lepidoptera" means scale-wing in Greek

Highly magnified view of a moth wing showing the very distinctive scales. The term "Lepidoptera" means scale-wing in Greek

Moths and butterflies are the most popular and widely studied group of insects in the British Isles. The first significant book on them was Moses Harris's "The Aurelian Or Natural History Of English Insects; Namely, Moths And Butterflies. Together With The Plants On Which They Feed" published in 1776. The 19th and early 20th century craze for collecting butterflies (and their varieties) was partly responsible for the local extinction of a few species.