- Home

- Garden Wildlife

- Annelids

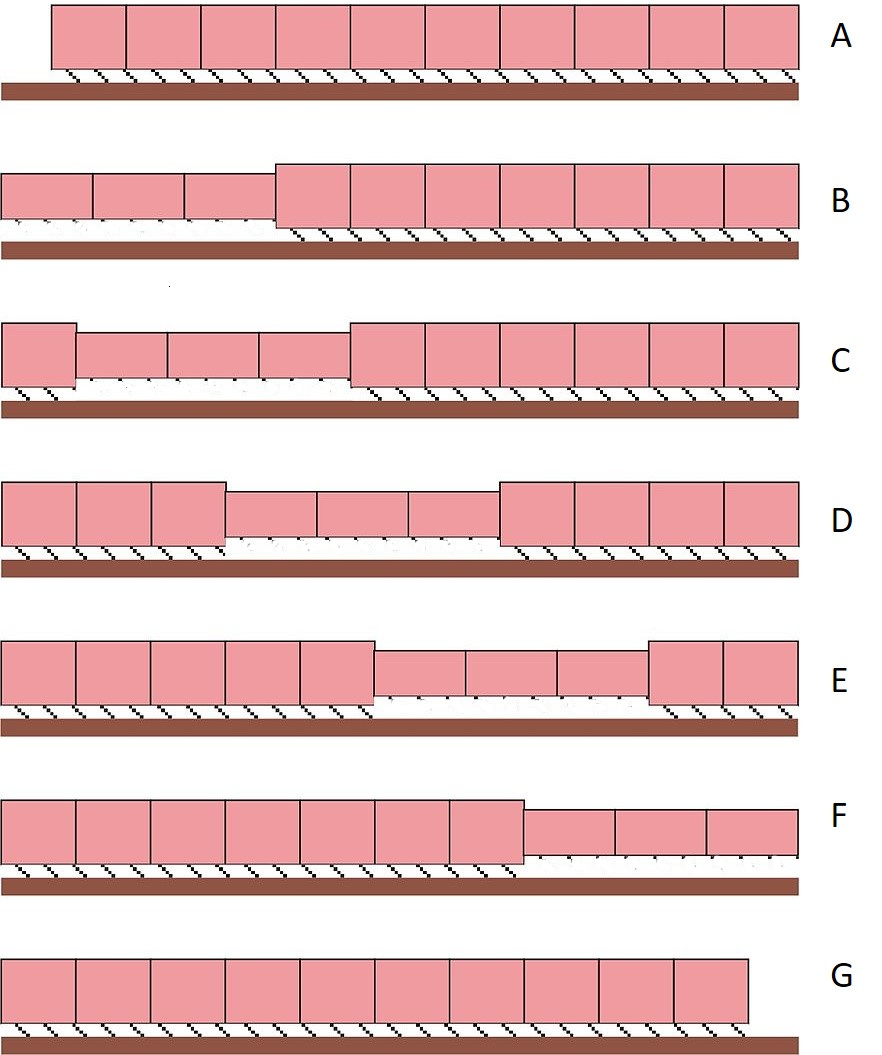

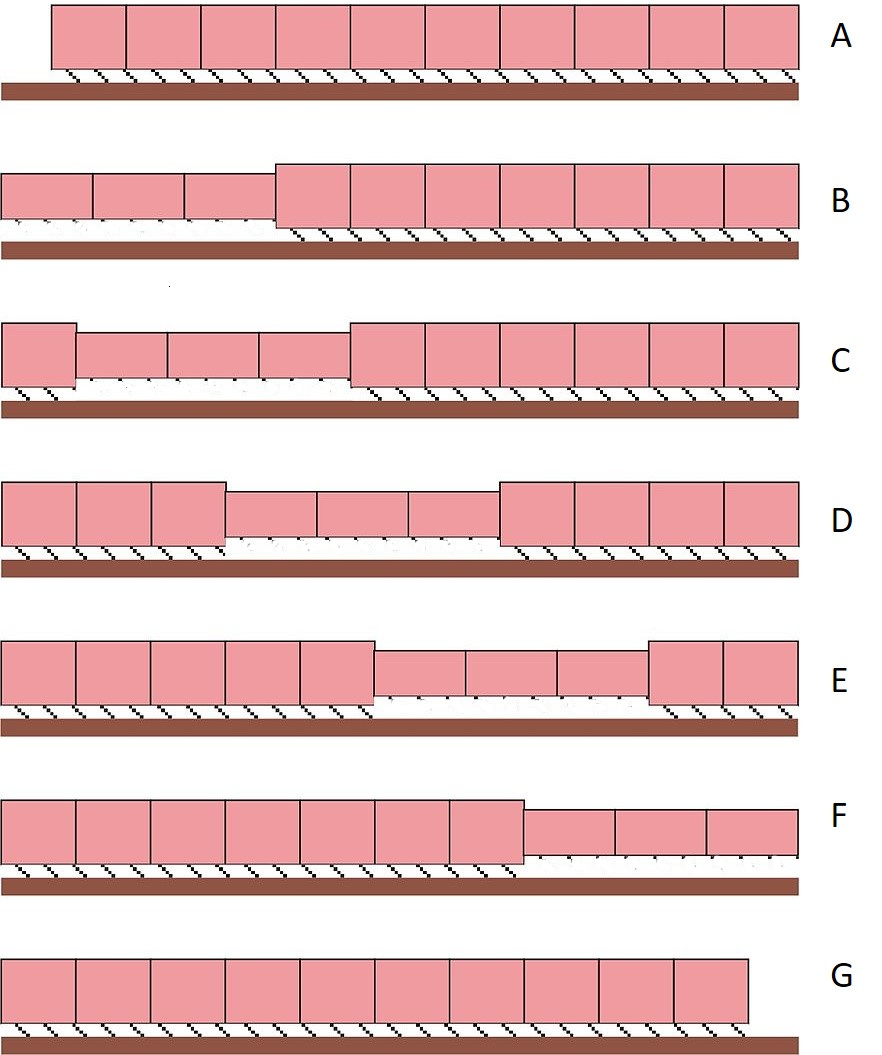

The worm's segments are shown as boxes, either short and wide, or long and thin depending on muscle contraction. The segments are sealed off from each other so can change shape uniquely. Circular muscles running around the segment contract to make it longer and thinner, while longitudinal muscles running from front to back in the segment make it shorter and fatter allowing it to grip the substrate with the chaetae.

At A. the worm is at rest. At B. the front 3 segments extend, with chaetae withdrawn. At C., the first segment shortens and widens, with chaetae extended to grip the substrate beyond where the worm's head was in A.

In C.,D., and E. the anterior segments shorten successively, and pull the posterior segments forward until at F. the most posterior segments are in motion.

At G. the move is complete and the whole worm is one unit forward. Note that as you watch the animal, the peristaltic wave is passing backwards while the worm is moving forwards.

In reality, many more segments are moving at once and the extension with each wave of contraction is much greater.

With upwards of 150 segments, worms can exert quite a considerable force, and their head can become narrow and pointed to push through the soil.

Oligochaetes live in soil, rotting material and some live in water. They are hermaphrodites, with complex mating behaviour, and adults can be recognised from a pale and often swollen structure called the clitellum between the fourteenth and seventeenth segments back from the head. It is used to secrete the mucus cocoon in which their eggs are laid.

Subclass Oligochaeta

The oligochaetes consist of earthworms and their relatives, globally about 10,000 species. They have elongate tubular segmented bodies with obvious lines or rings around the body that indicate the segments, but lack the parapodia of their polychaete relatives. All that remains of these are small retractable chaetae grouped in four sets of pairs on each segment, These allow the worm to get a grip on the soil surface or on its burrow wall and are important for locomotion and burrowing. How this works is shown in the diagram below

Front Rear

Left: Dozens of medicinal leeches Hirudo medicinalis swarming over waders in a well vegetated pond in Lower Saxony, Germany. Right: The partly healed Mercedes-logo mark left on human skin after a leech has fed. The wound usually keeps bleeding for a long time, because the leeches secrete hirudin, which is an anticoagulant.

Other sources of information

Websites

Annelid Resources website

Website of the Earthworm Society of Britain

Page drafted and compiled by Steve Head

Annelid worms

The segmented worms belong to the phylum Annelida, which contains over 22,000 species globally, found in the sea, on land and in freshwater. There are three main groups, and a couple of odd groups previously in different phyla are now classed with them. All annelids are segmented and in many of them this is very obvious, as the long thin body seems made up of rings stuck together. They have a gloriously wide range of feeding strategies and mechanisms, especially those that live in the sea. Two of the three main groups, the earthworms and leeches are found in gardens. The third and probably ancestral group, the polychaetes, is almost entirely marine.

Class Polychaeta

The 10,000 species of polychaetes comprise by far the most varied group of annelids, and indeed the others are considered to be derived from polychaete ancestors. They are characterised by having fleshy parapodia laterally on each segment, that work like legs when crawling and paddles when swimming. These parapodia carry long bristles called chaeta, which give the name to the group. The chaetae are stiff and made of chitin. Many polychaetes are hunting predators, with jaws within an eversible pharynx, and have complex heads with eyes and sendory tentacles.

Left: Large hunting polychaete Alitta virens , with its head to the left and obvious parapodia on each side. Right: isolated parapodium fro a diffrent species showing its two lobes, dorsal and ventral, and the long chitin bristles used in swimming and walking.

Polychaetes can locomote slowly just using their parapodia like legs. As they go faster, their body starts to wiggle sideways, until when swimming the whole worm is thrashing in a sinusoidal motion from side to side.

While many polychaetes move like this, there are also many sessile species. They stay in one place, usually inside some form of burrow or tube. Many of these have spectacular body structures for filtering seawater, like this peacock worm which is projecting its fan of tentacles out of the top of its mud and mucus tube.

Typical oligochaetes. Left, earthworm Lumbricus terrestris showing the clitellum near the head (to the right). Right: tiny white worms in the family Enchytraeidae.

Subclass Hirudinea

This contains the leeches, which are really highly modified oligochaetes, and the two subclassed are now put together into the class Clitellata because they share a clitellum which isn't present in the polychaetes, which shed their eggs and sperm into the sea.There are about 700 known leech species.

Leeches have lost external signs of segmentation, and evolved suckers at each end of their body. They can swim (badly) by wiggling like polychaetes, but more often by making looping movements, holding on with the rear sucker, and extending the whole body forward before then gripping with the head end and contracting the body to bring it forward.

Most leeches live in freshwater, but some live in damp rainforests on land, and a few live in the sea.Most leeches are parasites which feed on the blood of vertebrate hosts, but about a quarter (including most British and Irish species) are predators of small pond animals. Parasitic leeches have three sharp teeth in their mouth, which leave a characteristic Y shaped wound on the unfortunate host. The medicinal leech, illustrated below, is very rare in Britain and absent from Ireland, and isn't found in garden ponds. Thankfully.

Annelid worms

The segmented worms belong to the phylum Annelida, which contains over 22,000 species globally, found in the sea, on land and in freshwater. There are three main groups, and a couple of odd groups previously in different phyla are now classed with them. All annelids are segmented and in many of them this is very obvious, as the long thin body seems made up of rings stuck together. They have a gloriously wide range of feeding strategies and mechanisms, especially those that live in the sea. Two of the three main groups, the earthworms and leeches are found in gardens. The third and probably ancestral group, the polychaetes, is almost entirely marine.

Class Polychaeta

The 10,000 species of polychaetes comprise by far the most varied group of annelids, and indeed the others are considered to be derived from polychaete ancestors. They are characterised by having fleshy parapodia laterally on each segment, that work like legs when crawling and paddles when swimming. These parapodia carry long bristles called chaeta, which give the name to the group. The chaetae are stiff and made of chitin. Many polychaetes are hunting predators, with jaws within an eversible pharynx, and have complex heads with eyes and sendory tentacles.

Left: Large hunting polychaete Alitta virens , with its head to the left and obvious parapodia on each side. Right: isolated parapodium fro a diffrent species showing its two lobes, dorsal and ventral, and the long chitin bristles used in swimming and walking.

Polychaetes can locomote slowly just using their parapodia like legs. As they go faster, their body starts to wiggle sideways, until when swimming the whole worm is thrashing in a sinusoidal motion from side to side.

While many polychaetes move like this, there are also many sessile species. They stay in one place, usually inside some form of burrow or tube. Many of these have spectacular body structures for filtering seawater, like this peacock worm which is projecting its fan of tentacles out of the top of its mud and mucus tube.

Subclass Oligochaeta

The oligochaetes consist of earthworms and their relatives, globally about 10,000 species. They have elongate tubular segmented bodies with obvious lines or rings around the body that indicate the segments, but lack the parapodia of their polychaete relatives. All that remains of these are small retractable chaetae grouped in four sets of pairs on each segment, These allow the worm to get a grip on the soil surface or on its burrow wall and are important for locomotion and burrowing. How this works is shown in the diagram below

Front Rear

The worm's segments are shown as boxes, either short and wide, or long and thin depending on muscle contraction. The segments are sealed off from each other so can change shape uniquely. Circular muscles running around the segment contract to make it longer and thinner, while longitudinal muscles running from front to back in the segment make it shorter and fatter allowing it to grip the substrate with the chaetae.

At A. the worm is at rest. At B. the front 3 segments extend, with chaetae withdrawn. At C., the first segment shortens and widens, with chaetae extended to grip the substrate beyond where the worm's head was in A.

In C.,D., and E. the anterior segments shorten successively, and pull the posterior segments forward until at F. the most posterior segments are in motion.

At G. the move is complete and the whole worm is one unit forward. Note that as you watch the animal, the peristaltic wave is passing backwards while the worm is moving forwards. In reality, many more segments are moving at once and the extension with each wave of contraction is much greater

With upwards of 150 segments, worms can exert quite a considerable force, and their head can become narrow and pointed to push through the soil.

Oligochaetes live in soil, rotting material and some live in water. They are hermaphrodites, with complex mating behaviour, and adults can be recognised from a pale and often swollen structure called the clitellum between the fourteenth and seventeenth segments back from the head. It is used to secrete the mucus cocoon in whih their eggs are laid.

Typical oligochaetes. Left, earthworm Lumbricus terrestris showing the clitellum near the head (to the right). Right: tiny white worms in the family Enchytraeidae.

Subclass Hirudinea

This contains the leeches, which are really highly modified oligochaetes, and the two subclassed are now put together into the class Clitellata because they share a clitellum which isn't present in the polychaetes, which shed their eggs and sperm into the sea.There are about 700 known leech species

Leeches have lost external signs of segmentation, and evolved suckers at each end of their body. They can swim (badly) by wiggling like polychaetes, but more often by making looping movements, holding on with the rear sucker, and extending the whole body forward before then gripping with the head end and contracting the body to bring it forward.

Most leeches live in freshwater, but some live in damp rainforests on land, and a few live in the sea. Most leeches are parasites which feed on the blood of vertebrate hosts, but about a quarter (including most British and Irish species) are predators of small pond animals. Parasitic leeches have three sharp teeth in their mouth, which leave a characteristic Y shaped wound on the unfortunate host. The medicinal leech, illustrated below, is very rare in Britain and absent from Ireland, and isn't found in garden ponds. Thankfully.

Left: Dozens of medicinal leeches Hirudo medicinalis swarming over waders in a well vegetated pond in Lower Saxony, Germany. Right: The partly healed Mercedes-logo mark left on human skin after a leech has fed. The wound usually keeps bleeding for a long time, because the leeches secrete hirudin, which is an anticoagulant.

Other sources of information

Websites

Annelid Resources website

Website of the Earthworm Society of Britain

Page drafted and compiled by Steve Head