Garden Wildlife

Garden Wildlife

Bird biology – birds are special!

Birds are an extremely successful group of organisms. Among the vertebrates, fish are much the biggest group – but of course their sea and freshwater habitat covers 71% of the globe! Birds tie with reptiles in second place. They dominate British and Irish land-breeding vertebrates and are by far the biggest group of vertebrates in gardens.

Birds are warm blooded

This is one thing birds have in common with mammals. Both groups maintain a relatively constant body temperature, often higher or lower than the temperature of their surroundings, and this means a high metabolic rate which enables them to be more effficient, fast responding and fast moving. Birds usually run at a higher temperature than mammals. For example, humans operate in health at around 37°C, while birds tend to operate at around 41°C. If you ever hold a small bird in your hand it often feels warm.

The down feathers form a very efficient insulting layer outside the skin of birds and some birds also maintain a layer of fat under their skin which also acts to insulate their bodies. Penguins are a good example of this, but many nestling seabirds such as fulmars and other petrels do so as well. There was a long tradition of killing and extracting the fat of “muttonbirds” for domestic purposes and there is still a regulated commercial industry.

Garden birds may also build up large fat deposits as energy reserves for winter and for migration. Birds like blackcaps can double their body weight in fat prior to their autumn migration. This emphasises the importance of gardens as food resources for such birds.

Birds have complicated respiratory systems and hollow bones

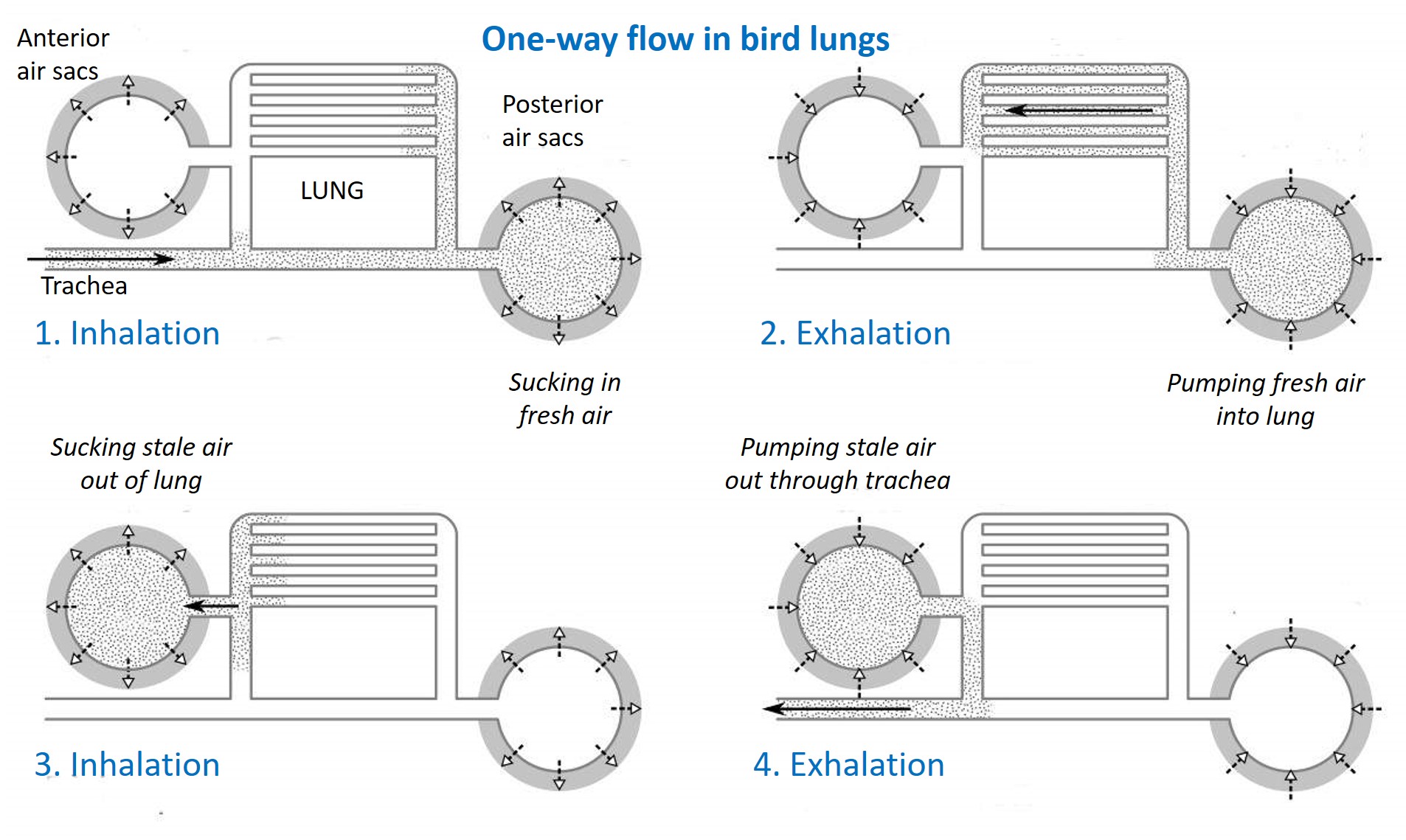

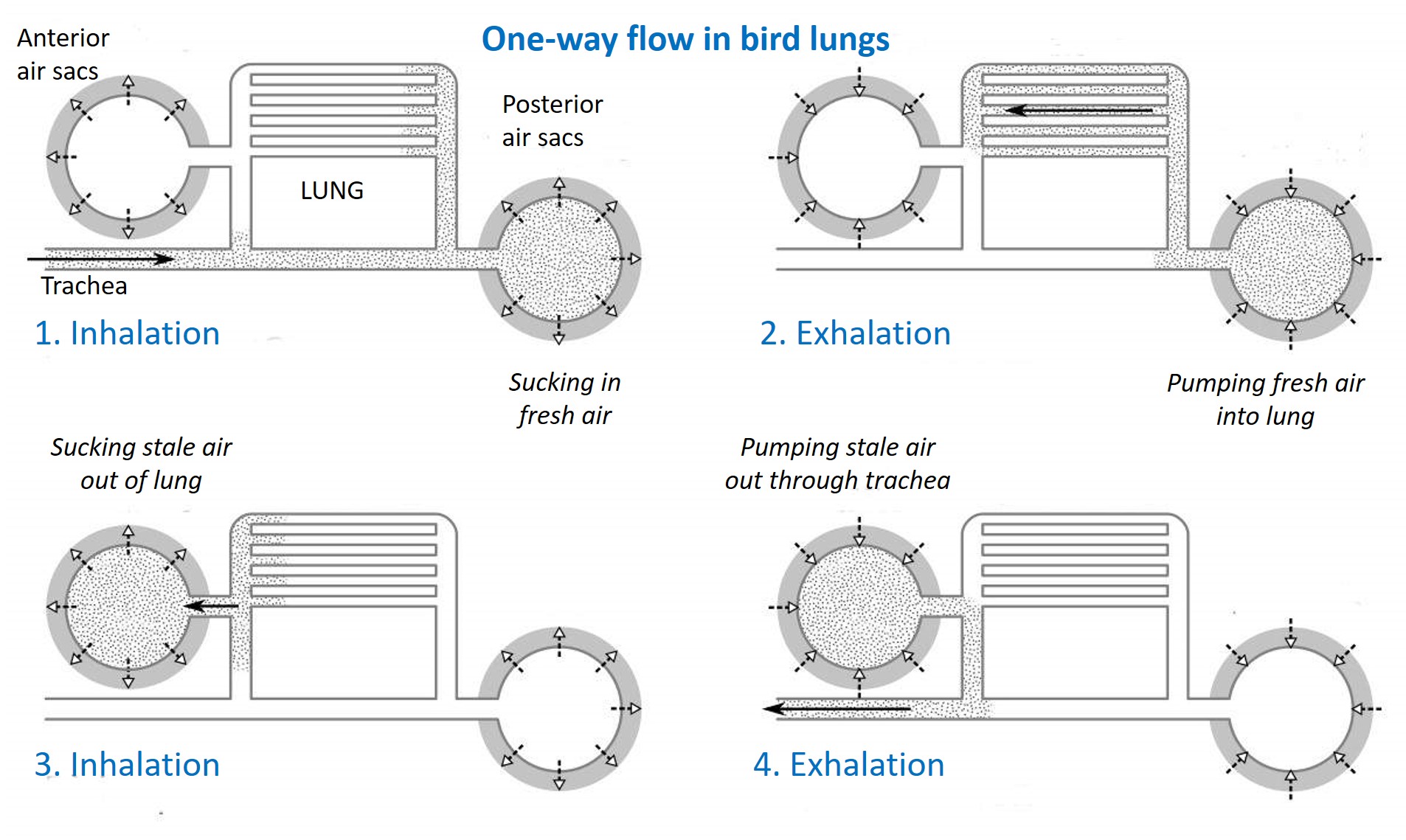

Linked to a high metabolic rate is high oxygen consumption and birds have a respiratory system that differs radically from that of mammals. Mammals have a single pathway in and out of their lungs, and air is exchanged at each breath by movements of the diaphragm and the rib cage – an inefficient ‘one-stroke’ breathing system where stale air always mixes with the fresh. Birds have a series of thin-walled air sacs connected to their lungs, which forms a much more efficient ‘two-stroke’ breathing system in which air always moves in one direction through a lung with "in and out" openings at both ends.

|

Group

|

Global species

|

UK species

|

UK native land breeding

|

In UK gardens

|

|

Birds

|

10,000

|

574

|

200

|

60+

|

|

Mammals

|

6,400

|

107

|

64

(18 are bats)

|

24

(5 bats)

|

|

Reptiles

|

10,000

|

6

|

6

|

3

|

|

Amphibia

|

6,000

|

7

|

7

|

5

|

|

Fish

|

25,000

|

340

|

-

|

-

|

Approximate numbers of vertebrate species

So why are birds so successful?

Flight – birds can fly!

Birds have wings for their front limbs, and their tail is short and used for steering and stabilising flight. This gives them huge advantages both for collecting food and evading being eaten, and in being able to migrate across the globe to track optimal weather and food availability.

The only downside is the need to keep relatively light (and so small) compared with non-flying land vertebrates.

The heaviest birds are all secondarily flightless. Flight is also one of the key advantages of the insects, and even in the mammals, the aerial bats are second only to the rodents in species diversity.

Feathers

These are unique to birds. They were present in bird’s dinosaur ancestors and probably evolved from reptilian scales as insulation. They create an extraordinarily light and effective wing aerofoil. Feathers are often involved in signalling between birds and also act as part of their camouflage when they hide from predators. Feathers have a bewildering array of colours and patterns. Browns, yellows and reds tend to be colours caused by pigments within the feather, mainly derived from melanin (like the colours in human skin), or from carotenes (often absorbed from colourful foods). Blues and greens tend to be ‘structural’ colours, formed by interference with light on grids of fine microscopic structures within the feather rather than pigments embedded within it.

The properties of feathers depend on their careful preservation and physical arrangement at a near microscopic level. Birds spend a lot of time maintaining their feathers by preening, dusting and bathing.

There are several different types of feather in modern birds. All feathers have a central shaft or rachis and vanes or downy fibres.

Flight feathers have a strong rachis and asymmetrical vanes, the leading edge shorter than the trailing edge creating an aerofoil shape giving extra lift.

These feathers form the lifting, propelling and steering surfaces of wings and tail, and are strong enough to maintain their shape during the stresses of flight.

Contour feathers are smaller and have a more symmetrical structure than flight feathers but retain the rachis and the closely linked vanes.

Contour feathers form an aerodynamically smooth outer covering to the body and limbs and carry most of the plumage pattern. They are fluffy at the base for insulation.

Down feathers have the vanes replaced by separated downy fibres which act as padding and insulation, and bulk out the body of the bird under the contour feathers. When you pluck a bird there are so many down feathers! The underlying body hardly resembles the outer shape of the clothed bird.

This insulation means birds can survive in extremely cold environments – think Penguins in Antarctica, and ducks on a cold lake.

Beaks (bills)

The jaws of birds are extended by horny structures which we recognise as beaks or bills. They are primarily for feeding, but also enable birds to carry out delicate manipulation of their environment and body. Watch a bird feeding, watch it preening, watch it gathering nest material. The bill is an amazingly versatile organ and makes up in very large part for the lack of hands/paws or whatever on their forelimbs.

The shape of a bird’s bill is linked closely to their diet and other aspects of their behaviour. This provides a major clue when it comes to identifying and understanding more about birds in the garden. For instance the wren has a fine pointed bill, linked to its diet of tiny insects, while the greenfinch has a robust shorter bill linked to a diet of harder bulky seeds and the sparrowhawk has a powerful hooked bill for tearing meat.

_(14568723138).jpg)

Eggs and nests

Birds lay eggs, with hard shells, and look after them in nests. Eggs are attractive and interesting objects and in the past they were widely collected, with devastating effects on some populations of less abundant species. This is now illegal in the UK where bird nests and eggs are protected from human interference by law.

Eggs are highly edible and all sorts of creatures (including other birds and humans) seek them out as part of their diet. Nestlings are also easy food for many predators. Hence most birds are very secretive in their nesting habits.

Birds are warm blooded.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Most garden bird species build characteristic nests of some complexity. The blackbird nest is a typical cup nest of twigs, while the long-tailed tit nest is a more enclosed spherical affair built of moss and spiderweb. There are many variations!

Because of the one-way flow of air through the lungs, the blood supply in bird lungs is very much more efficient at extracting oxygen than that in mammal lungs (it is a counter-current exchanger, for the engineers among you). Oxygen-breathing mountaineers struggling step by step up Everest can watch birds effortlessly flying past at the same altitude.

The air sacs also penetrate many of the bones, making them hollow and much lighter than mammal bones ideal for flight.

Flying, walking and swimming

Birds are good movers. Different species of bird have different ‘styles’ of flight. Smaller, lighter birds like finches and sparrows tend to have short bursts of wing beats, interspersed with ‘ballistic’ glides with wings closed which reduces the air resistance against their light bodies. Larger birds like crows and pigeons can glide but tend to use powered flight when getting about over middle distances. Larger birds often use rising air thermals and glide on outstretched wings, circling to very high altitudes.

Birds have different modes of walking. Pied wagtails tend to walk left-right-left-right as we do. Others like dunnocks hop using both feet simultaneously. Blackbirds do both, walking about on the lawn and then hopping when they pounce on prey. Blue tits cling onto branches and clamber around upside down and sideways whilst seeking food among the buds and twigs. Smaller garden birds tend to be good at perching on small branches with their feet wrapped round for support. Their long claws make this easier.

Many birds are good at swimming above and even below the surface. Swimming is not something you see birds doing in most gardens, although many garden birds like to bathe when water is available. There is evidence that water can restore the shape of battered feathers which may account for this love of bathing.

Migration

Because they can fly many birds are able to move very long distances. This is obvious in our winter, when many birds leave and head south for equatorial regions, and birds of the Arctic move into our temperate areas where the cold is less severe. You might wonder why birds fly north to us to breed - it’s because temperate regions have a huge burst of insect and plant food available in spring and summer just right for feeding chicks. Bird ringing and modern tracking devices show some enormous feats of travel – one bar tailed godwit has been observed flying from Alaska to New Zealand non-stop.

In UK gardens some of our familiar birds leave for the south during winter while some are joined by or replaced by others of the same species from further north. Winter changes the feeding patterns of many of our birds. The tits tend to assemble in flocks and move through gardens en masse, so you may have ten of them there for a short period, and none for the rest of the day.

Garden bird ecology

Ecologically, birds fall into three main categories, although most garden birds are pretty much generalists in this respect. Often they will prey on insects during the spring and summer, and nuts, seeds and fruit in autumn and winter.

Carnivores: This brings to mind birds of prey, and the one that turns up most frequently in UK gardens is the sparrowhawk. This will catch and eat smaller birds sing a sneak attack strategy, hopping over hedges and walls without warning. Big ones tend to be female, and they can handle woodpigeons with a bit of luck. Smaller ones tend to be male, and naturally they eat smaller birds.

However, many of the smaller garden birds are also carnivores (or actually insectivores – i.e. they eat whole little creatures rather than bits of big ones). Wren and blackbird are good examples of these, although blackbirds also eat berries in winter. Blue tits slaughter many baby moths to feed their young.

Herbivores: The herbivores are well represented by greenfinch and goldfinch. They eat seeds and nuts primarily and other plant items (like spring buds) at other times of year, House sparrow adults are mainly seed eating, but they use insect food as protein-rich high-energy nutrition for their chicks, demonstrating another blurring of the ecological boundaries.

Scavengers: The various crows tend to be scavengers of dead meat, killed by other things (e.g. roadkill, cat kill, sparrowhawk leftovers) – hence the name “carrion crow”. If you live in some parts of the UK red kites might also be part of your garden birdlife – people put out meat scraps for these determined scavengers.

Page written by Roy Smith and compiled by Steve Head

Air is sucked into the body by muscles acting on the bones of the thorax, into the rear air sacs.

When the bird breathes out, this air from the rear air sacs is squeezed through the lungs and on the next intake of breath it is sucked into the front end air sacs.

Next time the bird breathes out, this stale air from the front sacs is squeezed back out of the trachea.

Bird biology – birds are special!

Birds are an extremely successful group of organisms. Among the vertebrates, fish are much the biggest group – but of course their sea and freshwater habitat covers 71% of the globe! Birds tie with reptiles in second place. They dominate British and Irish land-breeding vertebrates and are by far the biggest group of vertebrates in gardens.

|

Group

|

Global species

|

UK species

|

UK native land breeding

|

In UK gardens

|

|

Birds

|

10,000

|

574

|

200

|

60+

|

|

Mammals

|

6,400

|

107

|

64

(18 are bats)

|

24

(5 bats)

|

|

Reptiles

|

10,000

|

6

|

6

|

3

|

|

Amphibia

|

6,000

|

7

|

7

|

5

|

|

Fish

|

25,000

|

340

|

-

|

-

|

Approximate numbers of vertebrate species

So why are birds so successful?

Flight – birds can fly!

Birds have wings for their front limbs, and their tail is short and used for steering and stabilising flight. This gives them huge advantages both for collecting food and evading being eaten, and in being able to migrate across the globe to track optimal weather and food availability.

The only downside is the need to keep relatively light (and so small) compared with non-flying land vertebrates.

The heaviest birds are all secondarily flightless. Flight is also one of the key advantages of the insects, and even in the mammals, the aerial bats are second only to the rodents in species diversity.

Feathers

These are unique to birds. They were present in bird’s dinosaur ancestors and probably evolved from reptilian scales as insulation. They create an extraordinarily light and effective wing aerofoil. Feathers are often involved in signalling between birds and also act as part of their camouflage when they hide from predators. Feathers have a bewildering array of colours and patterns. Browns, yellows and reds tend to be colours caused by pigments within the feather, mainly derived from melanin (like the colours in human skin), or from carotenes (often absorbed from colourful foods). Blues and greens tend to be ‘structural’ colours, formed by interference with light on grids of fine microscopic structures within the feather rather than pigments embedded within it.

The properties of feathers depend on their careful preservation and physical arrangement at a near microscopic level. Birds spend a lot of time maintaining their feathers by preening, dusting and bathing.

There are several different types of feather in modern birds. All feathers have a central shaft or rachis and vanes or downy fibres.

Flight feathers have a strong rachis and asymmetrical vanes, the leading edge shorter than the trailing edge creating an aerofoil shape givings and tail, and are strong enough to maintain their shape during the stresses of flight. ng extra lift.

These feathers form the lifting, propelling and steering surfaces of wings and tail, and are strong enough to maintain their shape during the stresses of flight.

Contour feathers are smaller and have a more symmetrical structure than flight feathers but retain the rachis and the closely linked vanes.

Contour feathers form an aerodynamically smooth outer covering to the body and limbs and carry most of the plumage pattern. They are fluffy at the base for insulation.

Down feathers have the vanes replaced by separated downy fibres which act as padding and insulation, and bulk out the body of the bird under the contour feathers. The underlying body hardly resembles the outer shape of the clothed bird.

This insulation means birds can survive in extremely cold environments – think Penguins in Antarctica, and ducks on a cold lake. When you pluck a bird there are so many down feathers!

Beaks (bills)

The jaws of birds are extended by horny structures which we recognise as beaks or bills. They are primarily for feeding, but also enable birds to carry out delicate manipulation of their environment and body. Watch a bird feeding, watch it preening, watch it gathering nest material. The bill is an amazingly versatile organ and makes up in very large part for the lack of hands/paws or whatever on their forelimbs.

The shape of a bird’s bill is linked closely to their diet and other aspects of their behaviour. This provides a major clue when it comes to identifying and understanding more about birds in the garden. For instance the wren has a fine pointed bill, linked to its diet of tiny insects, while the greenfinch has a robust shorter bill linked to a diet of harder bulky seeds and the sparrowhawk has a powerful hooked bill for tearing meat.

_(14568723138).jpg)

Eggs and nests

Birds lay eggs, with hard shells, and look after them in nests. Eggs are attractive and interesting objects and in the past they were widely collected, with devastating effects on some populations of less abundant species. This is now illegal in the UK where bird nests and eggs are protected from human interference by law.

Most garden bird species build characteristic nests of some complexity. The blackbird nest is a typical cup nest of twigs, while the long-tailed tit nest is a more enclosed spherical affair built of moss and spiderweb. There are many variations!

.jpg)

.jpg)

Birds are warm blooded

This is one thing birds have in common with mammals. Both groups maintain a relatively constant body temperature, often higher or lower than the temperature of their surroundings, and this means a high metabolic rate which enables them to be more effficient, fast responding and fast moving. Birds usually run at a higher temperature than mammals. For example, humans operate in health at around 37°C, while birds tend to operate at around 41°C. If you ever hold a small bird in your hand it often feels warm.

The down feathers form a very efficient insulting layer outside the skin of birds and some birds also maintain a layer of fat under their skin which also acts to insulate their bodies. Penguins are a good example of this, but many nestling seabirds such as fulmars and other petrels do so as well. There was a long tradition of killing and extracting the fat of “muttonbirds” for domestic purposes and there is still a regulated commercial industry.

Garden birds may also build up large fat deposits as energy reserves for winter and for migration. Birds like blackcaps can double their body weight in fat prior to their autumn migration. This emphasises the importance of gardens as food resources for such birds.

Birds have complicated respiratory systems and hollow bones

Linked to a high metabolic rate is high oxygen consumption and birds have a respiratory system that differs radically from that of mammals. Mammals have a single pathway in and out of their lungs, and air is exchanged at each breath by movements of the diaphragm and the rib cage – an inefficient ‘one-stroke’ breathing system where stale air always mixes with the fresh. Birds have a series of thin-walled air sacs connected to their lungs, which forms a much more efficient ‘two-stroke’ breathing system in which air always moves in one direction through a lung with "in and out" openings at both ends.

Air is sucked into the body by muscles acting on the bones of the thorax, into the rear air sacs.

When the bird breathes out, this air from the rear air sacs is squeezed through the lungs and on the next intake of breath it is sucked into the front end air sacs.

Next time the bird breathes out, this stale air from the front sacs is squeezed back out of the trachea.

Because of the one-way flow of air through the lungs, the blood supply in bird lungs is very much more efficient at extracting oxygen than that in mammal lungs (it is a counter-current exchanger, for the engineers among you). Oxygen-breathing mountaineers struggling step by step up Everest can watch birds effortlessly flying past at the same altitude.

The air sacs also penetrate many of the bones, making them hollow and much lighter than mammal bones ideal for flight.

Flying, walking and swimming

Birds are good movers. Different species of bird have different ‘styles’ of flight. Smaller, lighter birds like finches and sparrows tend to have short bursts of wing beats, interspersed with ‘ballistic’ glides with wings closed which reduces the air resistance against their light bodies. Larger birds like crows and pigeons can glide but tend to use powered flight when getting about over middle distances. Larger birds often use rising air thermals and glide on outstretched wings, circling to very high altitudes.

Birds have different modes of walking. Pied wagtails tend to walk left-right-left-right as we do. Others like dunnocks hop using both feet simultaneously. Blackbirds do both, walking about on the lawn and then hopping when they pounce on prey. Blue tits cling onto branches and clamber around upside down and sideways whilst seeking food among the buds and twigs. Smaller garden birds tend to be good at perching on small branches with their feet wrapped round for support. Their long claws make this easier.

Many birds are good at swimming above and even below the surface. Swimming is not something you see birds doing in most gardens, although many garden birds like to bathe when water is available. There is evidence that water can restore the shape of battered feathers which may account for this love of bathing.

Migration

Because they can fly many birds are able to move very long distances. This is obvious in our winter, when many birds leave and head south for equatorial regions, and birds of the Arctic move into our temperate areas where the cold is less severe. You might wonder why birds fly north to us to breed - it’s because temperate regions have a huge burst of insect and plant food available in spring and summer just right for feeding chicks. Bird ringing and modern tracking devices show some enormous feats of travel – one bar tailed godwit has been observed flying from Alaska to New Zealand non-stop.

In UK gardens some of our familiar birds leave for the south during winter while some are joined by or replaced by others of the same species from further north. Winter changes the feeding patterns of many of our birds. The tits tend to assemble in flocks and move through gardens en masse, so you may have ten of them there for a short period, and none for the rest of the day.

Garden bird ecology

Ecologically, birds fall into three main categories, although most garden birds are pretty much generalists in this respect. Often they will prey on insects during the spring and summer, and nuts, seeds and fruit in autumn and winter.

Carnivores: This brings to mind birds of prey, and the one that turns up most frequently in UK gardens is the sparrowhawk. This will catch and eat smaller birds sing a sneak attack strategy, hopping over hedges and walls without warning. Big ones tend to be female, and they can handle woodpigeons with a bit of luck. Smaller ones tend to be male, and naturally they eat smaller birds.

However, many of the smaller garden birds are also carnivores (or actually insectivores – i.e. they eat whole little creatures rather than bits of big ones). Wren and blackbird are good examples of these, although blackbirds also eat berries in winter. Blue tits slaughter many baby moths to feed their young.

Herbivores: The herbivores are well represented by greenfinch and goldfinch. They eat seeds and nuts primarily and other plant items (like spring buds) at other times of year, House sparrow adults are mainly seed eating, but they use insect food as protein-rich high-energy nutrition for their chicks, demonstrating another blurring of the ecological boundaries.

Scavengers: The various crows tend to be scavengers of dead meat, killed by other things (e.g. roadkill, cat kill, sparrowhawk leftovers) – hence the name “carrion crow”. If you live in some parts of the UK red kites might also be part of your garden birdlife – people put out meat scraps for these determined scavengers.

Residents and visitors

Page written by Roy Smith and compiled by Steve Head

Eggs are highly edible and all sorts of creatures (including other birds and humans) seek them out as part of their diet. Nestlings are also easy food for many predators. Hence most birds are very secretive in their nesting habits.