- Home

- Garden Wildlife

- Insects introduction

Introduction to Insects

The importance of insects

There are about a million described insect species, and it's estimated there may be 6 million or more as yet undescribed, accounting for more than half of all life on earth. They are dominant on land, abundant in freshwater, but hardly represented in the sea, where the related Crustacea take over.

We have over 24,000 species of insects in the UK, and even here in our highly studied country, there are probably many more to be found. Jennifer Owen found 1,992 insect species in her own garden, including some previously unknown to science

Basic insect structure

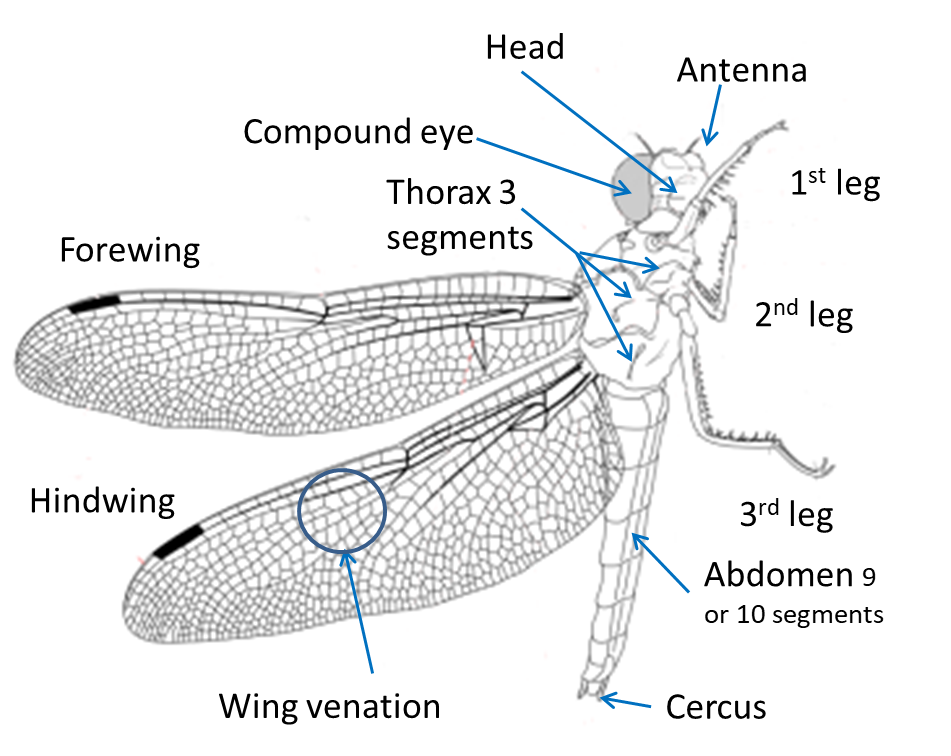

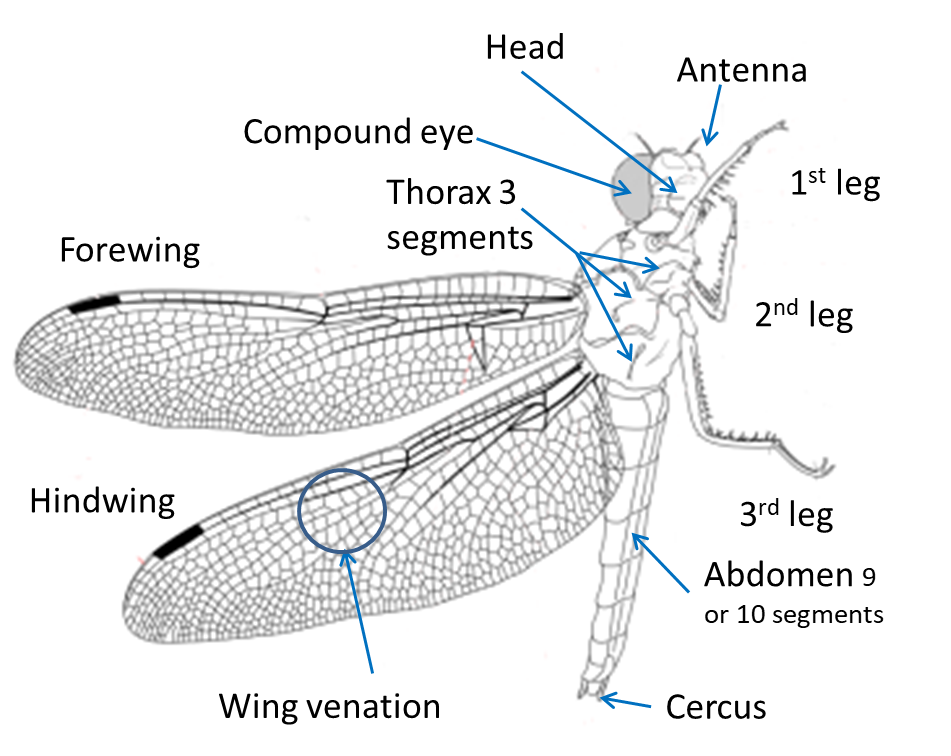

Like other arthropods adult insects are segmented animals, but in all of them the body is divided into three regions, the head (5-7 segments fused), the thorax (three segments, usually distinct) and the abdomen with 9-10 distinct segments. The head has one pair of antennae and a pair of compound eyes. Several modified limbs on the head serve as mouthparts. Adult insects have limbs on all three thoracic segments, and usually two pairs of wings, on the second and third thoracic segments. There are no limbs on the abdomen, but there may be structures called cerci on the end segment.

Almost none of these characteristics (except segmentation) are true for many insect larvae!

Insect life histories

All insects, like other arthropods, have to moult or shed their tough external skeleton or exoskeleton several times as they grow, a process called ecdysis, because unlike vertebrate skin or our internal skeleton, it can't grow with the rest of the animal. The growth stages between each ecdysis are called instars. There's little doubt that this process (called ecdysis) is dangerous, since the newly emerged insect is pretty helpless when it has just emerged from its old skin, before the new one hardens and becomes usable to walk, fly or swim.

On the other hand, insects take advantage of ecdysis by using it to create a change in the body form after successive moults. In many, there is change and growth in adult features such as wings, but this is not sudden, but becomes more noticeable with each successive moult. The juvenile body form gradually changes to that of the adult. This is called incomplete metamorphosis, although "gradual metamorphosis" might be a better term. The young stages, which resemble the adult, are callyed nymphs, or nymphal stages. This growth pattern is considered primitive, and is typical of the grasshoppers, cockroaches, stick insects, termites and true bugs. Just to be difficult, you will find the terms exopterygote or hemimetabolous used as well.

_female_underside.jpg)

You should be able to spot the three pairs of legs, both wings, the head, thorax and abdomen, the big eye and the antennae on this silver-spotted skipper butterfly

Adult insects nearly always have males and females, which can differ substantially in appearance, with some females even being flightless. A few, but very important insects such as aphids are fully or partially parthenogenetic, females reproducing for some or all of the year without males.

Why are insects so successful?

This is a classic undergraduate essay topic, and like so many isues in biology, there isn't a clear answer. Firstly, the arthropod body design is a major element, and other arthropods such as crustaceans and spiders are also very succesful. The apparent drawback of growth by ecdysis is probably a major advantage, allowing larvae and adults to exist without competing with one another for resources. Certainly, the most succesful insect orders have complete metamorphosis.

The insect exoskeleton is wonderfully adapted for life on land, and avoiding desiccation, being very watertight. Insects limit water loss from breathing by being able to close the spiracles that connect their internal breathing tubes to the outside. They also lose little water from excretion by dumping their nitrogen waste as insoluble uric acid.

The last obvious major factor in insect success is flight. There are some primitively flightless insect groups, but these are not rich in species. Some insects have become secondarily flightless, through parasitism (like fleas) or with flightless females, but these are the exceptions. The flying insects vastly outnumber the flightless ones, in the same way that the most successful land vertebrates (birds and bats) are also flying. Flight enable distribution over very large distances, allowing migration through the year as the weather changes, and being able to locate and lay eggs on rare host food plants.

Major groups in UK gardens

This website attempts to provide a working introduction, with references to take you further, into all the insect groups you are likely to find in the garden. We will concentrate most on the less popular groups, while butterflies for example are extremely well covered in many websites.

Insects are most conveniently addressed within Orders, and then at the level of Family

The key orders are:

Coleoptera: Beetles

Hemiptera: True Bugs

Hymenoptera: Bees wasps and ants

Lepidoptera: Butterflies and moths

- but there are lots more which you can find through the menu system.

Further information

Website

Amateur Entomologists' Society Key to the orders of British adult insects

Books

Paul D. Brock 2014 A Comprehensive Guide to Insects of Britain & Ireland. Publisher Nature Bureau

Richard Lewington 2008 Guide to Garden Wildlife. British Wildlife Publishing

Michael Chinery 1993 Insects of Britain & Northern Europe Collins Field Guide

Page drafted and edited by Steve Head, reviewed by Andrew Salisbury

![Photo: Dick Culbert from Gibsons, B.C., Canada [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](images/Schistocerca_gregaria_(21530461886).jpg)

This shows an adult and two nymphs of the desert locust Schistocerca gregaria. The nymph on the right is one stage earlier (and smaller) than the one on the left, and its wings are hardly visible. The older nymph has the beginnings of wings appearing on top of its thorax.

Desert locusts are quite often recorded in Britain, but they will be escapees from captivity.

The majority of British insects have a different growth pattern, in which there are radical shape changes between the juvenile stages (called larvae) and the adult insect. This allows the ecology of the larva and adult to be completely different, with the larval stages centred on feeding and growing, while the main role of the adults is to mate, reproduce and disperse. Butterflies for example hatch from an egg, undergo up to 7 instars as caterpillars without much shape change but huge body growth. Then then moult into a pupa, which is a resting, immobile stage, during which the entire body is rebuilt internally to grow the final adult form. This is termed complete metamorphosis, or again to be awkward, holometabolous or endopterygote development.

![Photo: Muséum de Toulouse [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]](images/Pieris_brassicae_(caterpillar).jpg)

![Photo: Olbertz (talk) 15:46, 5 September 2008 (UTC) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)], from Wikimedia Commons](images/Couple_of_Pieris_brassicae_6277.jpg)

Large white butterfly life stages clockwise from top left.

Cluster of eggs on a brassica leaf

Caterpillar larva on a brassica flower head

Pupa or chrysalis, note the silk patch the abdomen is anchored on, and the silk strap holding it to the substrate.

Adult female (above) and male

Introduction to Insects

By Steve Head reviewed by Andrew Salisbury

The importance of insects

There are about a million described insect species, and it's estimated there may be 6 million or more as yet undescribed, accounting for more than half of all life on earth. They are dominant on land, abundant in freshwater, but hardly represented in the sea, where the related Crustacea take over.

We have over 24,000 species of insects in the UK, and even here in our highly studied country there are probably many more to be found. Jennifer Owen found 1,992 insect species in her own garden, including some previously unknown to science

Basic insect structure

Basic insect structure

Like other arthropods adult insects are segmented animals, but in all of them the body is divided into three regions, the head (5-7 segments fused), the thorax (three segments, usually distinct) and the abdomen with 9-10 distinct segments. The head has one pair of antennae and a pair of compound eyes. Several modified limbs on the head serve as mouthparts. Adult insects have limbs on all three thoracic segments, and usually two pairs of wings, on the second and third thoracic segments. There are no limbs on the abdomen, but there may be structures called cerci on the end segment.

Almost none of these characteristics (except segmentation) are true for many insect larvae!

_female_underside.jpg)

You should be able to spot the three pairs of legs, both wings, the head, thorax and abdomen, the big eye and the antennae on this silver-spotted skipper butterfly

Insect life histories

All insects, like other arthropods, have to moult or shed their tough external skeleton or exoskeleton several times as they grow, a process called ecdysis, because unlike vertebrate skin or our internal skeleton, it can't grow with the rest of the animal. The growth stages between each ecdysis are called instars. There's little doubt that this process (called ecdysis) is dangerous, since the newly emerged insect is pretty helpless when it has just emerged from its old skin, before the new one hardens and becomes usable to walk, fly or swim.

On the other hand, insects take advantage of ecdysis by using it to create a change in the body form after successive moults. In many, there is change and growth in adult features such as wings, but this is not sudden, but becomes more noticeable with each successive moult. The juvenile body form gradually changes to that of the adult. This is called incomplete metamorphosis, although "gradual metamorphosis" might be a better term. The young stages, which resemble the adult, are callyed nymphs, or nymphal stages. This growth pattern is considered primitive, and is typical of the grasshoppers, cockroaches, stick insects, termites and true bugs. Just to be difficult, you will find the terms exopterygote or hemimetabolous used as well.

![Photo: Dick Culbert from Gibsons, B.C., Canada [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](images/Schistocerca_gregaria_(21530461886).jpg)

This shows an adult and two nymphs of the desert locust Schistocerca gregaria. The nymph on the right is one stage earlier (and smaller) than the one on the left, and its wings are hardly visible. The older nymph has the beginnings of wings appearing on top of its thorax.

Desert locusts are quite often recorded in Britain, but they will be escapees from captivity.

The majority of British insects have a different growth pattern, in which there are radical shape changes between the juvenile stages (called larvae) and the adult insect. This allows the ecology of the larva and adult to be completely different, with the larval stages centred on feeding and growing, while the main role of the adults is to mate, reproduce and disperse. Butterflies for example hatch from an egg, undergo up to 7 instars as caterpillars without much shape change but huge body growth. Then then moult into a pupa, which is a resting, immobile stage, during which the entire body is rebuilt internally to grow the final adult form. This is termed complete metamorphosis, or again to be awkward, holometabolous or endopterygote development.

![Photo: Muséum de Toulouse [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]](images/Pieris_brassicae_(caterpillar).jpg)

![Photo: Olbertz (talk) 15:46, 5 September 2008 (UTC) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)], from Wikimedia Commons](images/Couple_of_Pieris_brassicae_6277.jpg)

Large white butterfly life stages clockwise from top left. Cluster of eggs on a brassica leaf; Caterpillar larva on a brassica flower head; Pupa or chrysalis, note the silk patch the abdomen is anchored on, and the silk strap holding it to the substrate. Adult female (above) and male

Adult insects nearly always have males and females, which can differ substantially in appearance, with some females even being flightless. A few, but very important insects such as aphids are fully or partially parthenogenetic, females reproducing for some or all of the year without males.

Why are insects so successful?

This is a classic undergraduate essay topic, and like so many isues in biology, there isn't a clear answer. Firstly, the arthropod body design is a major element, and other arthropods such as crustaceans and spiders are also very succesful. The apparent drawback of growth by ecdysis is probably a major advantage, allowing larvae and adults to exist without competing with one another for resources. Certainly, the most succesful insect orders have complete metamorphosis.

The insect exoskeleton is wonderfully adapted for life on land, and avoiding desiccation, being very watertight. Insects limit water loss from breathing by being able to close the spiracles that connect their internal breathing tubes to the outside. They also lose little water from excretion by dumping their nitrogen waste as insoluble uric acid.

The last obvious major factor in insect success is flight. There are some primitively flightless insect groups, but these are not rich in species. Some insects have become secondarily flightless, through parasitism (like fleas) or with flightless females, but these are the exceptions. The flying insects vastly outnumber the flightless ones, in the same way that the most successful land vertebrates (birds and bats) are also flying. Flight enable distribution over very large distances, allowing migration through the year as the weather changes, and being able to locate and lay eggs on rare host food plants.

Major groups in UK gardens

This website attempts to provide a working introduction, with references to take you further, into all the insect groups you are likely to find in the garden. We will concentrate most on the less popular groups, while butterflies for example are extremely well covered in many websites.

The key orders are:

Hemiptera: True Bugs

Diptera: Flies

Hymenoptera: Bees wasps and ants

Lepidoptera: Butterflies and moths

- but there are lots more which you can find through the menu system.

Further information

Website

Amateur Entomologists' Society Key to the orders of British adult insects

Books

Paul D. Brock 2014 A Comprehensive Guide to Insects of Britain & Ireland. Publisher Nature Bureau

Richard Lewington 2008 Guide to Garden Wildlife. British Wildlife Publishing

Michael Chinery 1993 Insects of Britain & Northern Europe Collins Field Guide