- Home

- Garden Wildlife

- Molluscs

- Garden slugs

Garden slugs

Garden slugs are all members of the air breathing "pulmonates" group of gastropods alongside their shelled compatriots the snails. In fact, all our slugs are descended from snails which have evolved to lose (or highly reduce) their shell. This has happened many times in evolution, and the various families of slugs are not all closely related to each other, except back through shelled snail ancestors.

Why be a slug?

Snails are well adapted to life on land. Their hard shell gives a useful degree of protection against predators, but it is especially important in protecting the snail from drying out in warm dry air. The mucus layer on the rest of the snail's body when out of the shell also helps, but this the only dessication protection available to slugs. There must be a good reason for losing the shell - since several lineages of slugs have done so, in the sea as well as on land. What are the advantages of losing the external shell? Here are Robert Cameron's suggestions, from his highly recommended book listed below:

• Shells are heavy, and slugs generally can move faster than snails (still not very fast!)

• Shells require a lot of calcium, which has to come from food. In chalky places this is easy, but where the soil is

acidic, calcium is hard to get and snails are much less common than slugs. Even when calcium is abundant, there

must still be some metabolic cost in making the shell.

• Losing the shell means the slug is entirely soft-bodied. and can squeeze through small apertures, and especially

between particles of soil, in a way impossible to snails. Instead of carrying a defensive home on their backs,

they can hide away in all sorts of confined spaces. Many land slugs are largely soil-living, and it seems the

main advantage of "sluggishness" is the greater ability to make use of small spaces.

Most slugs have very strong mucus-secreting powers, and in addition taste foul, so they are better defended than they appear.

The shell of snails was almost certainly the main reason why pulmonates were able to evolve to live on land, but slugs have become successful precisiely because - once adapted to land - they were able to ditch the shell. An exact parallel can be seen in the cephalopod molluscs They were able to become swimming predators by using their coiled shell for bouyancy - as in modern Nautilus and fossil ammonites. However, the modern cephalopods, especially the squid and octopus, have become even more successful through abandoning the bouyant shell, and maintaining their position in the water by other means.

Having said this many slugs do retain a vestige of an internal shell - a useful calcium store, and some such as Testacella have a very small external shell. Equally, especially in the tropics, there are many species of semi-slugs which are snails which have reduced their shell to a greater or lesser extent.

Slug anatomy

Golden shelled slug Testacella scutulum

Biology of slugs

Most slugs seek shelter in the soil or under logs and stones during cold weather but do not become dormant. They can be active throughout the year as long as temperatures are a few degrees above freezing point.

Role of slugs in gardens

Not all slugs are villains in the garden, and generally the smaller ones are the most damaging. Unlike snails, which are generally surface living, many slugs feed underground and are damaging for potatoes and other root crops. Many species feed on decaying plant material rather than growing plants.

Seedlings and very young plants are particularly at risk, and when they are strong enough to plant out they are at lower risk. There are many suggested repellents, but while some like eggshells or wool may work for a while, they cease to be effective after rain. Copper bands do seem to work, but cease to be so effective as they corrode. We do not recommend using slug pellets in the open garden, but there is every reason to use them in closed greenhouses or cold frames.

Slugs are cryptic, often distasteful and produce repellent mucus, so appear not to be as often eaten as snails. Slugs and their eggs are eaten by carabid beetles, some flies and probably many other taxa. It is less clear which vertebrates eat them, because tell-tale shells are not left behind as is the case with snails. Frogs and toads eat them, as do slowworms. Thrushes and blackbirds will take them, and jaw parts of Deroceras reticulatum have been found in starling droppings.

Other sources of information

Website

Website of the Conchological Society of Great Britain and Ireland

Brian Eversham's guide to identifying land snails on NatureSpot

CABI information on Spanish slug

Books

Cameron, R. (2016) Slugs and Snails. New Naturalist Series Harper Collins London

Rowson, B., Turner, J., Anderson, R. & Symondson, B. (2014) Slugs of Britain and Ireland. A Field Studies Council AIDGAP key

Page drafted by Andrew Halstead, reviewed by Andrew Salisbury, extended and compiled by Steve Head

Species in Britain and Ireland

We have 46 species of slugs in Britain, belonging to seven families. Jennifer Owen recorded 7 species in her study, while slug-specialist Robert Cameron found 22 in his Sheffield garden. For convenience we can divide the slugs into three groups, the round-backed slugs, which belong in the genus Arion in the family Arionidae, the keeled slugs (in the families Agriolimacidae, Boettgerillidae, Milacidae, and Limacidae) and the shelled slugs in the genus Testacella in the family Testacellidae

Round-backed slugs

These slugs have their pneumostome near the front of the mantle, and can contract under threat to a slimy hemispherical blob which must be very difficult to attack. There are up to 15 species of Arion in Britain and Ireland, and Jennifer Owen recorded four in her garden. The largest species is the large black slug, Arion ater which grows to 15cm (when fully extended). Pale when young, it is generally jet black when mature, and it looks for all the world like a large piece of well licked liquorice. Another species, Arion rufus, is also common and is almost identical to A. ater anatomically, but is rusty-brown or red, but colour isn't always a reliable character. These big slugs are mainly eaters of dead and dying vegetation, and rarely a problem in the garden. The southern garden slug, Arion hortensis is much more of a problem. It is up to 35mm long, dark grey-black above and with an orange coloured sole to its foot. Arion distinctus is very similar but with gold speckles on the tubercles on its back. The rusty false-keeled slug Arion fasciatus is up to 40mm long, yellow-brown and with a pale sole.

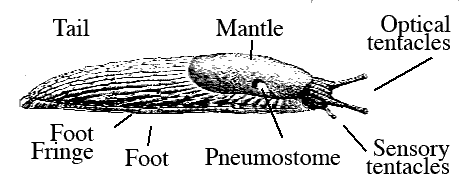

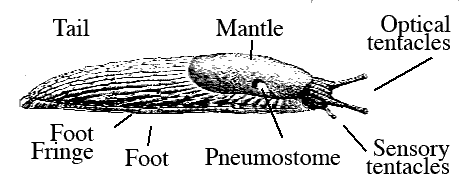

Externally, most of the slug body is its locomotory foot, very much the same as that of snails. Without a shell, the mantle forms the "back" of the slug behind the head, and under it lies the respiratory mantle cavity. Air is exchanged in and out of this lung via the pneumostome, and its position is a marker for slug identification. The round-backed slugs have (as in this picture) the pneumostome on the right side towards the front of the mantle. In keeled slugs it is towards the rear.

Large black slug Arion ater. Left: typical shiny black form - showing the pneumostome very clearly, Top right: Red form probably Arion rufus. Bottom right: A. ater contracted to a defensive blob

Above: Left: Garden slug Arion hortensis Right: Slug Arion distinctus

Left: Slug Arion fasciatus

The highly invasive Spanish slug Arion vulgaris, grows to 12cm length and is very variable in colour. It is a non-native species that has recently been identified as widespread in the east of England where it was first recorded in 1954. It is probably native to France and northern Spain but has colonised all of Europe and is now in North America. It is considered a significant agricultural and ecological threat.

Spanish slug Arion vulgaris in its typical reddish colour, and fully extended. It can occasionally be found with a dark almost black colour.

Keeled slugs

Of the British and Irish slugs, keeled slugs, Sowerby's slug Tandonia sowerbyi and the Budapest slug Tandonia budapestensis have the longest keels. They are medium sized slugs that mainly feed underground and are a serious pest on potatoes and arable fields.

Budapest slug Tandonia budapestensis Drawing of Sowerby's slug Tandonia sowerbyi

Other common garden slugs include the grey garden slug, Deroceras reticulatum which has a netted appearance from its skin tubercles, and a short rear keel. It is about 5cm long, and exudes a milky mucus when disturbed. It is probably the most destructive and disliked of slugs in the garden - where they are abundant. The yellow slug Limacus flavus is larger at 10cm long. It has blueish tentacles and isn't a pest, feeding mainly on detritus.

The worm slug Boettgerilla pallens is only 4cm when extended and thin and worm-like, adapted to a largely subterranean life. Introduced and spreading since 1972, it isn't a pest and even eats eggs of other slugs.

Shell-bearing slugs

This last group contains only three species in Britain and Ireland. The only garden species the golden-shelled slug Testacella scutulum is now considered to have included a second species Testacella sp "tenuipenis". They are instantly recognisable from the small posterior external oval shell, and a marked groove on either side of the body. Testacella is common and up to 10cm long, but is rarely seen, since it lives in the soil, predating earthworms and other slugs.

Above: the pesky gray or netted garden slug Deroceras reticulatum Right: Yellow slug Limacus flavus

Below: Worm slug Boettgerilla pallens

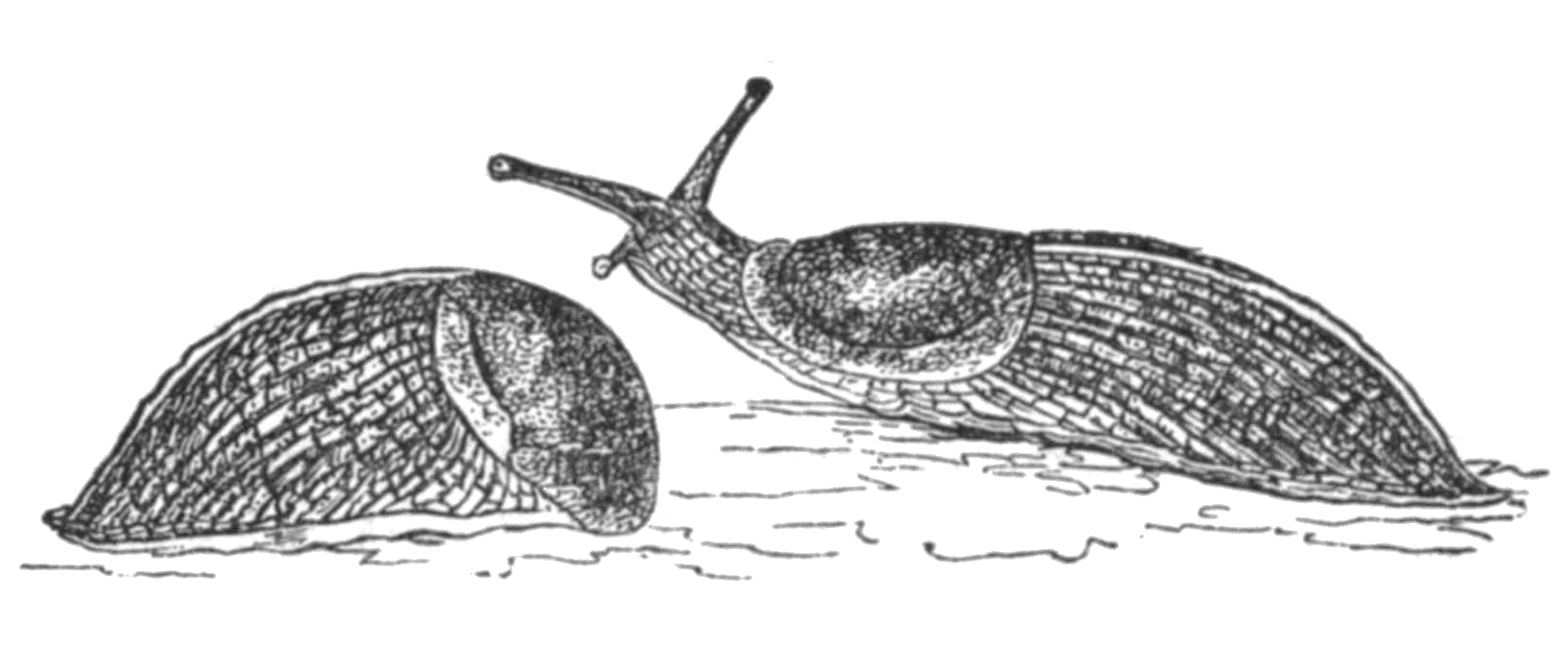

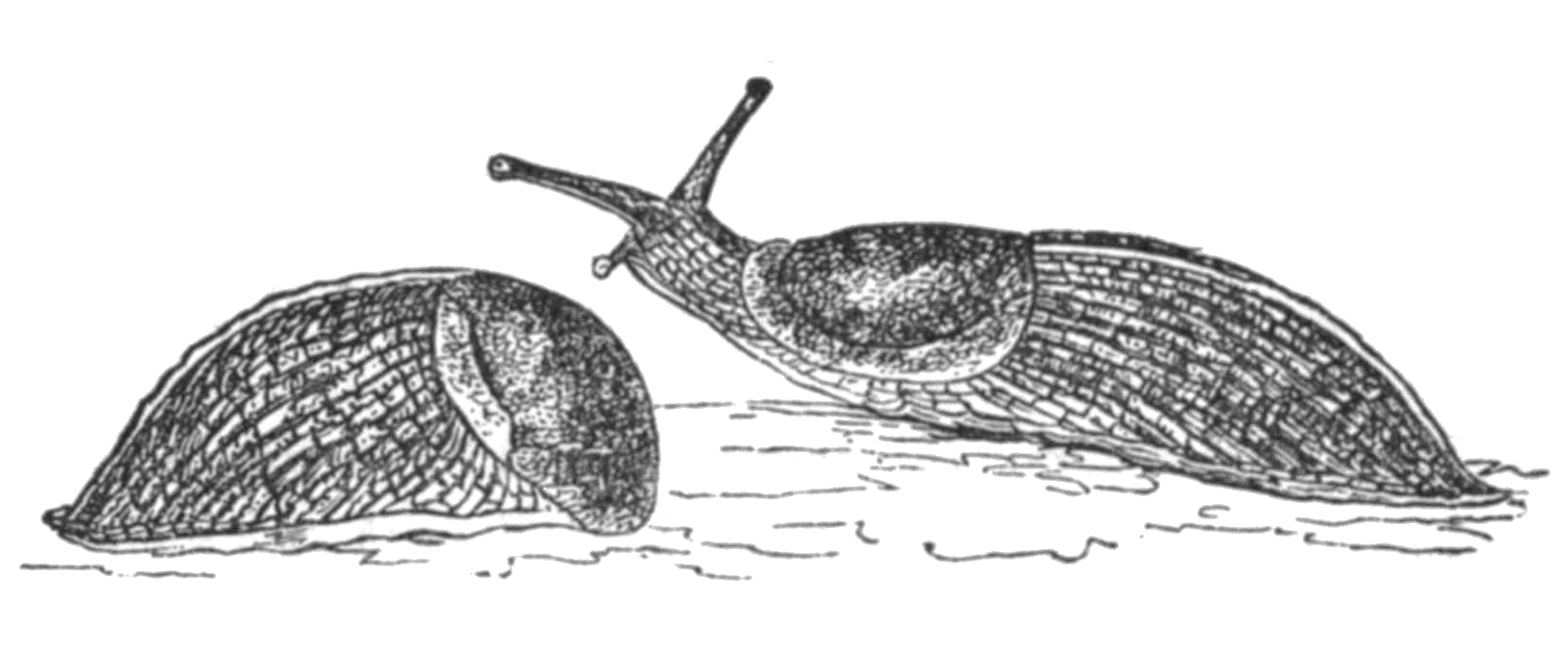

The great grey or leopard slug Limax maximus, is up to 15cm or more long. Named from its black spotted marking, it is also not damaging, feeding on fungi and rotting material. Its spectacular suspended mating ritual is discussed in our Mollusc introduction page.

Leopard slug.

Below: Like many slugs the leopard slug has a thin 13mm internal shell only visible on dissection. It probably serves as a calcium reserve

Garden slugs

Garden slugs are all members of the air breathing "pulmonates" group of gastropods alongside their shelled compatriots the snails. In fact, all our slugs are descended from snails which have evolved to lose (or highly reduce) their shell. This has happened many times in evolution, and the various families of slugs are not all closely related to each other, except back through shelled snail ancestors.

Why be a slug?

Snails are well adapted to life on land. Their hard shell gives a useful degree of protection against predators, but it is especially important in protecting the snail from drying out in warm dry air. The mucus layer on the rest of the snail's body when out of the shell also helps, but this the only dessication protection available to slugs. There must be a good reason for losing the shell - since several lineages of slugs have done so, in the sea as well as on land. What are the advantages of losing the external shell? Here are Robert Cameron's suggestions, from his highly recommended book listed below:

• Shells are heavy, and slugs generally can move faster than snails (still not very

fast!)

• Shells require a lot of calcium, which has to come from food. In chalky places

this is easy, but where the soil is acidic, calcium is hard to get and snails are

much less common than slugs. Even when calcium is abundant, there must still

be some metabolic cost in making the shell.

• Losing the shell means the slug is entirely soft-bodied. and can squeeze

through small apertures, and especially between particles of soil, in a way

impossible for snails. Instead of carrying a defensive home on their backs, they

can hide away in all sorts of confined spaces. Many land slugs are largely

soil-living, and it seems the main advantage of "sluggishness" is the greater

ability to make use of small spaces.

Most slugs have very strong mucus-secreting powers, and in addition taste foul, so they are better defended than they appear.

The shell of snails was almost certainly the main reason why pulmonates were able to evolve to live on land, but slugs have become successful precisiely because - once adapted to land - they were able to ditch the shell. An exact parallel can be seen in the cephalopod molluscs They were able to become swimming predators by using their coiled shell for bouyancy - as in modern Nautilus and fossil ammonites. However, the modern cephalopods, especially the squid and octopus, have become even more successful through abandoning the bouyant shell, and maintaining their position in the water by other means.

Having said this many slugs do retain a vestige of an internal shell - a useful calcium store, and some such as Testacella have a very small external shell. Equally, especially in the tropics, there are many species of semi-slugs which are snails which have reduced their shell to a greater or lesser extent.

Slug anatomy

Externally, most of the slug body is its locomotory foot, very much the same as that of snails. Without a shell, the mantle forms the "back" of the slug behind the head, and under it lies the respiratory mantle cavity. Air is exchanged in and out of this lung via the pneumostome, and its position is a marker for slug identification. The round-backed slugs have (as in this picture) the pneumostome on the right side towards the front of the mantle. In keeled slugs it is towards the rear.

Species in Britain and Ireland

We have 46 species of slugs in Britain, belonging to seven families. Jennifer Owen recorded 7 species in her study, while slug-specialist Robert Cameron found 22 in his Sheffield garden. For convenience we can divide the slugs into three groups, the round-backed slugs, which belong in the genus Arion in the family Arionidae, the keeled slugs (in the families Agriolimacidae, Boettgerillidae, Milacidae, and Limacidae) and the shelled slugs in the genus Testacella in the family Testacellidae

Round-backed slugs

These slugs have their pneumostome near the front of the mantle, and can contract under threat to a slimy hemispherical blob which must be very difficult to attack. There are up to 15 species of Arion in Britain and Ireland, and Jennifer Owen recorded four in her garden. The largest species is the large black slug, Arion ater which grows to 15cm (when fully extended). Pale when young, it is generally jet black when mature, and it looks for all the world like a large piece of well licked liquorice. Another species, Arion rufus, is also common and is almost identical to A. ater anatomically, but is rusty-brown or red, but colour isn't always a reliable character. These big slugs are mainly eaters of dead and dying vegetation, and rarely a problem in the garden. The southern garden slug, Arion hortensis is much more of a problem. It is up to 35mm long, dark grey-black above and with an orange coloured sole to its foot. Arion distinctus is very similar but with gold speckles on the tubercles on its back. The rusty false-keeled slug Arion fasciatus is up to 40mm long, yellow-brown and with a pale sole.

Large black slug Arion ater. Left: typical shiny black form - showing the pneumostome very clearly, Top right: Red form probably Arion rufus. Bottom right: A. ater contracted to a defensive blob

Above: Left: Garden slug Arion hortensis Right: Slug Arion distinctus

Below: Slug Arion fasciatus

The highly invasive Spanish slug Arion vulgaris, grows to 12cm length and is very variable in colour. It is a non-native species that has recently been identified as widespread in the east of England where it was first recorded in 1954. It is probably native to France and northern Spain but has colonised all of Europe and is now in North America. It is considered a significant agricultural and ecological threat.

Spanish slug Arion vulgaris in its typical reddish colour, and fully extended. It can occasionally be found with a dark almost black colour.

Keeled slugs

Of the British and Irish slugs, keeled slugs, Sowerby's slug Tandonia sowerbyi and the Budapest slug Tandonia budapestensis have the longest keels. They are medium sized slugs that mainly feed underground and are a serious pest on potatoes and arable fields.

Budapest slug Tandonia budapestensis Sowerby's slug Tandonia sowerbyi

Other common garden slugs include the grey garden slug, Deroceras reticulatum which has a netted appearance from its skin tubercles, and a short rear keel. It is about 5cm long, and exudes a milky mucus when disturbed. It is probably the most destructive and disliked of slugs in the garden - where they are abundant. The yellow slug Limacus flavus is larger at 10cm long. It has blueish tentacles and isn't a pest, feeding mainly on detritus.

The worm slug Boettgerilla pallens is only 4cm when extended and thin and worm-like, adapted to a largely subterranean life. Introduced and spreading since 1972, it isn't a pest and even eats eggs of other slugs.

Shell-bearing slugs

This last group contains only three species in Britain and Ireland. The only garden species the golden-shelled slug Testacella scutulum is now considered to have included a second species Testacella sp "tenuipenis". They are instantly recognisable from the small posterior external oval shell, and a marked groove on either side of the body. Testacella is common and up to 10cm long, but is rarely seen, since it lives in the soil, predating earthworms and other slugs.

Above: Leopard slug Limax maximus

Right:Like many slugs the leopard slug has a thin 13mm internal shell only visible on dissection. It probably serves as a calcium reserve

The great grey or leopard slug Limax maximus, is up to 15cm or more long. Named from its black spotted marking, it is also not damaging, feeding on fungi and rotting material. Its spectacular suspended mating ritual is discussed in our Mollusc introduction page.

Above: the pesky gray or netted garden slug Deroceras reticulatum Right: Yellow slug Limacus flavus

Below: Worm slug Boettgerilla pallens

Golden shelled slug Testacella scutulum

Biology of slugs

Most slugs seek shelter in the soil or under logs and stones during cold weather but do not become dormant. They can be active throughout the year as long as temperatures are a few degrees above freezing point.

Role of slugs in gardens

Not all slugs are villains in the garden, and generally the smaller ones are the most damaging. Unlike snails, which are generally surface living, many slugs feed underground and are damaging for potatoes and other root crops. Many species feed on decaying plant material rather than growing plants.

Seedlings and very young plants are particularly at risk, and when they are strong enough to plant out they are at lower risk. There are many suggested repellents, but while some like eggshells or wool may work for a while, they cease to be effective after rain. Copper bands do seem to work, but cease to be so effective as they corrode. We do not recommend using slug pellets in the open garden, but there is every reason to use them in closed greenhouses or cold frames.

Slugs are cryptic, often distasteful and produce repellent mucus, so appear not to be as often eaten as snails. Slugs and their eggs are eaten by carabid beetles, some flies and probably many other taxa. It is less clear which vertebrates eat them, because tell-tale shells are not left behind as is the case with snails. Frogs and toads eat them, as do slowworms. Thrushes and blackbirds will take them, and jaw parts of Deroceras reticulatum have been found in starling droppings.

Other sources of information

Website

Brian Eversham's guide to identifying land snails on NatureSpot

CABI information on Spanish slug

Books

Cameron, R. (2016) Slugs and Snails. New Naturalist Series Harper Collins London

Rowson, B., Turner, J., Anderson, R. & Symondson, B. (2014) Slugs of Britain and Ireland. A Field Studies Council AIDGAP key

Page drafted by Andrew Halstead, reviewed by Andrew Salisbury, extended and compiled by Steve Head