- Home

- Garden Wildlife

- Flatworms

Flatworms (and nemerteans)

Flatworms are simple animals in the phylum Platyhelminthes. This group also contains the flukes and tape worms which are parasites that probably occur in gardens inside the bodies of birds and mammals, but which we aren't discussing further here. The garden flatworms are grouped into the traditional class Turbellaria or free-living flatworms, but this isn't a sound taxonomic grouping or clade. The native British and Irish flatworms can be divided into land-living and pond-living species, and there are important non-native species to consider as well.

Flatworms have a solid body and no circulatory system, which confines them to a small size and flat structure so that they can absorb enough oxygen through their skin. They have a mouth, but it isn't at the front of the body, instead about half way down on the underside, in the form of a slit through which a muscular pharynx can be everted. Most have no anus, discharging what material they need to get rid of back through the mouth. They have sophisticated excretory and nervous systems and can show fairly complex behaviour. They are mostly hermaphrodites using internal fertilisation.

Species in Britain and Ireland

Land flatworms

We have 4 native land species and at least 17 non-native species, mostly from the southern hemisphere. All are predators, often on earthworms or scavengers of dead animal material. They can be mistaken for slugs, and best distinguished by their lack of tentacles and patterning on the skin surface.

We have 3 native land flatworm species in the genus Microplana plus the uncommon Rynchodesmus sylvaticus. They all have a single pair of eyes at the front of their body, while the two common non-native species have large numbers of tiny eyes.

A South American invasive species, the Obama flatworm (Obama nungara), was first reported here in a plant pot in 2016 It is spreading across Europe and is already a problem in France. It has been found sporadically in Britain in garden centres. It is up to 7cm long with a brown or black upper surface, and a pale ventral surface. It eats earthworms and molluscs, and is considered extremely invasive, and a significant threat to soil ecosystems.

Our two commonest native land flatworms, Left: Microplana scharffi (2-5cm long) Right: Microplana terrestris which is 1-2cm long.

The non-native flatworms include two established species causing great concern because they are voracious predators of earthworms.

The Australian flatworm Australoplana sanguinea 2-8cm was first recorded in 1980 and is now widespread in southern England, Wales and Ireland. It is a distinctive bright orange colour and can be very abundant where it is found, in one Southport garden over 5,000 individuals in ten years1. It seems to reproduce largely by fission, shedding the rear section which then develops a new head.

The New Zealand flatworm Arthurdendyus triangulatus reaches 20cm length. It was first found here in Northern Ireland in the 1960's and is now common in gardens in Central and Southern Scotland, Northern England, and Northern Ireland. It seems to need cool conditions and can't cope with dry soil. When found, it is usually coiled up. It reproduces sexually and makes "shiny black egg capsules about the size of a large blackcurrant."1

It has been shown that these worms greatly reduce the abundance and diversity of earthworm species in a short time. The New Zealand flatworm is particularly dangerous for the deep-burrowing "anecic" worms like Lumbricus terrestris. This not only affects soil structure but is bad news for animals like moles that also eat earthworms.

Above: New Zealand flatworm Arthurdendyus triangulatus, head to the right. Below Left: the same species, in the coiled posture in which it is usually found hiding under stones. Right: Australian flatworm Australoplana sanguinea

Life cycle

Flatworms are hermaphrodite, but need another individual as a partner to reproduce sexually. They are internally fertilised, and lay eggs which hatch into tiny versions of their parents. In addition, many flatworms reproduce by cloning themselves, either splitting into two or budding off new individuals.

Role of flatworms in gardens

Native land and pond flatworms are natural garden beasts and cause no problems, but the non-native invaders are extremely voracious earthworm consumers which can cause damage to the soil structure and ecosystem. We don't know what their long term effects will be as they become more widely distributed, but there is some hope they will come into balance with their prey, but probably with far fewer earthworms left.

For completeness - nemertean worms

Another worm phylum exists in Britain and Ireland, the Nemertea. These are distantly related to flatworms, molluscs and annelids. They most resemble flatworms in general structure, but are more cyclindrical, with a circulatory system, anus and a unique eversible proboscis. Nearly all are marine (we have a number of species around our coasts) but a few are terrestrial/ freshwater. There are two (probably only one really) described native species of Prosoma, known from a few ponds and rivers, and two non-native species from the southern hemisphere, Antiponemertes pantini and Argonemertes dendyi which has been recorded sporadically in damp woodland. It is conceivable that A. dendyi may find their way into gardens, but these small (15mm) worms do not seem to pose any threat to our fauna, unlike the non-native invasive flatworms.

Invasive flatworm Obama nungara. On the right one is eating an earthworm, and the pale everted pharynx is visible wrapped around the head of the worm.

What to do if you find an invasive flatworm in your garden

Report the find to the GB non-native species secretariat on their website. There isn't much you can do to get rid of them once they have arrived. If you put down black plastic sheets you may find the worms congregate underneath and can be removed. Prevention is better than cure, and the most likely way to introduce them to your garden is through buying plants imported with soil from overseas. You could also do Buglife's flatworm survey to see what species you can find in your garden.

Pond flatworms

In addition to the terrrestrial species we have 13 species which live in freshwater, mostly in clean flowing water, but some can live in ponds. They are small (12-20mm) slow moving and inconspicuous. Some feed on decaying material, but generally they are predators on small invertebrates. The species most likely to be seen in garden ponds are Dendrocoelum lacteum, Polycelis nigra and Schmidtea polychroa.

Above left: Dendrocoelum lacteum recognisable by its milky colour. Above right: Schmidtea polychroa (once Dugesia polychroa). Left: Polycelis nigra.

Our two commonest native land flatworms, Left: Microplana scharffi (2-5cm long) Right: Microplana terrestris which is 1-2cm long.

The non-native flatworms include two established species causing great concern because they are voracious predators of earthworms.

The Australian flatworm Australoplana sanguinea 2-8cm was first recorded in 1980 and is now widespread in southern England, Wales and Ireland. It is a distinctive bright orange colour and can be very abundant where it is found, in one Southport garden over 5,000 individuals in ten years1. It seems to reproduce largely by fission, shedding the rear section which then develops a new head.

The New Zealand flatworm Arthurdendyus triangulatus reaches 20cm length. It was first found here in Northern Ireland in the 1960's and is now common in gardens in Central and Southern Scotland, Northern England, and Northern Ireland. It seems to need cool conditions and can't cope with dry soil. When found, it is usually coiled up. It reproduces sexually and makes "shiny black egg capsules about the size of a large blackcurrant."1

It has been shown that these worms greatly reduce the abundance and diversity of earthworm species in a short time. The New Zealand flatworm is particularly dangerous for the deep-burrowing "anecic" worms like Lumbricus terrestris. This not only affects soil structure but is bad news for animals like moles that also eat earthworms.

Flatworms (and nemerteans)

Flatworms are simple animals in the phylum Platyhelminthes. This group also contains the flukes and tape worms which are parasites that probably occur in gardens inside the bodies of birds and mammals, but which we aren't discussing further here. The garden flatworms are grouped into the traditional class Turbellaria or free-living flatworms, but this isn't a sound taxonomic grouping or clade. The native British and Irish flatworms can be divided into land-living and pond-living species, and there are important non-native species to consider as well.

Flatworms have a solid body and no circulatory system, which confines them to a small size and flat structure so that they can absorb enough oxygen through their skin. They have a mouth, but it isn't at the front of the body, instead about half way down on the underside, in the form of a slit through which a muscular pharynx can be everted. Most have no anus, discharging what material they need to get rid of back through the mouth. They have sophisticated excretory and nervous systems and can show fairly complex behaviour. They are mostly hermaphrodites using internal fertilisation.

Species in Britain and Ireland

Land flatworms

We have 4 native land species and at least 17 non-native species, mostly from the southern hemisphere. All are predators, often on earthworms or scavengers of dead animal material. They can be mistaken for slugs, and best distinguished by their lack of tentacles and patterning on the skin surface.

We have 3 native land flatworm species in the genus Microplana plus the uncommon Rynchodesmus sylvaticus. They all have a single pair of eyes at the front of their body, while the two common non-native species have large numbers of tiny eyes.

Above: New Zealand flatworm Arthurdendyus triangulatus, head to the right. Below Left: the same species, in the coiled posture in which it is usually found hiding under stones. Right: Australian flatworm Australoplana sanguinea

A South American invasive species, the Obama flatworm (Obama nungara), was first reported here in a plant pot in 2016 It is spreading across Europe and is already a problem in France. It has been found sporadically in Britain in garden centres. It is up to 7cm long with a brown or black upper surface, and a pale ventral surface. It eats earthworms and molluscs, and is considered extremely invasive, and a significant threat to soil ecosystems.

Invasive flatworm Obama nungara. On the right one is eating an earthworm, and the pale everted pharynx is visible wrapped around the head of the worm.

What to do if you find an invasive flatworm in your garden

Report the find to the GB non-native species secretariat on their website. There isn't much you can do to get rid of them once they have arrived. If you put down black plastic sheets you may find the worms congregate underneath and can be removed. Prevention is better than cure, and the most likely way to introduce them to your garden is through buying plants imported with soil from overseas. You could also do Buglife's flatworm survey to see what species you can find in your garden.

Pond flatworms

In addition to the terrrestrial species we have 13 species which live in freshwater, mostly in clean flowing water, but some can live in ponds. They are small (12-20mm) slow moving and inconspicuous. Some feed on decaying material, but generally they are predators on small invertebrates. The species most likely to be seen in garden ponds are Dendrocoelum lacteum, Polycelis nigra and Schmidtea polychroa.

Pond flatworms. Top: Dendrocoelum lacteum recognisable by its milky colour. Above: Schmidtea polychroa (once Dugesia polychroa). Below: Polycelis nigra.

Life cycle

Flatworms are hermaphrodite, but need another individual as a partner to reproduce sexually. They are internally fertilised, and lay eggs which hatch into tiny versions of their parents. In addition, many flatworms reproduce by cloning themselves, either splitting into two or budding off new individuals.

Role of flatworms in gardens

Native land and pond flatworms are natural garden beasts and cause no problems, but the non-native invaders are extremely voracious earthworm consumers which can cause damage to the soil structure and ecosystem. We don't know what their long term effects will be as they become more widely distributed, but there is some hope they will come into balance with their prey, but probably with far fewer earthworms left.

For completeness - nemertean worms

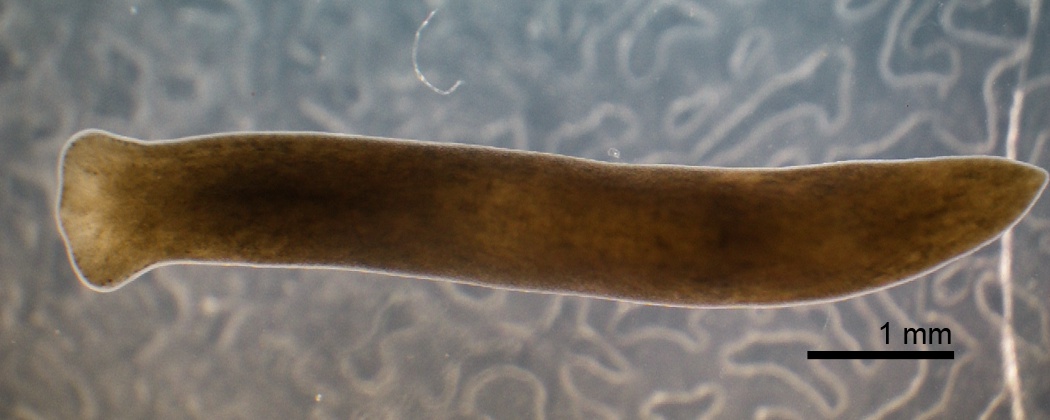

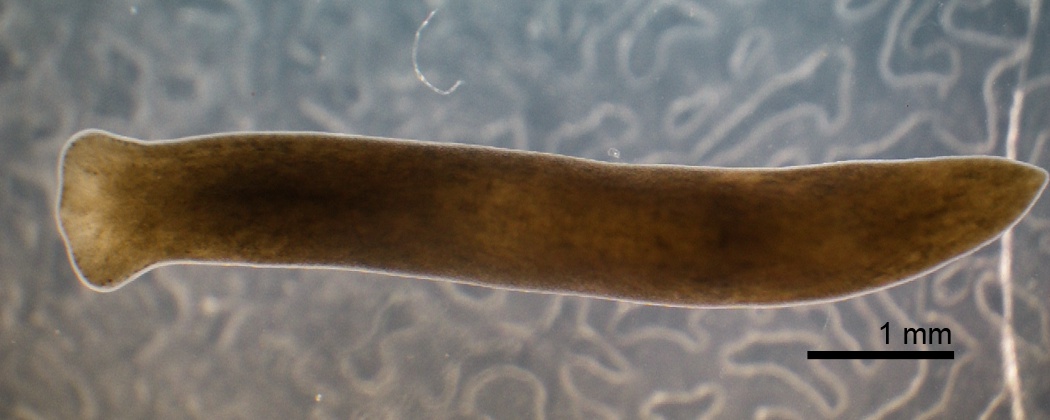

Another worm phylum exists in Britain and Ireland, the Nemertea. These are distantly related to flatworms, molluscs and annelids. They most resemble flatworms in general structure, but are more cyclindrical, with a circulatory system, anus and a unique eversible proboscis. Nearly all are marine (we have a number of species around our coasts) but a few are terrestrial/ freshwater. There are two (probably only one really) described native species of Prosoma, known from a few ponds and rivers, and two non-native species from the southern hemisphere, Antiponemertes pantini and Argonemertes dendyi which has been recorded sporadically in damp woodland. It is conceivable that A. dendyi may find their way into gardens, but these small (15mm) worms do not seem to pose any threat to our fauna, unlike the non-native invasive flatworms.

Reference:

1. Jones, H.D. 2005. Identification: British land flatworms. British Wildlife 16(3): 189-194.

Other sources of information

Websites

Non-native Species Secretariat ID information on non-native flatworms

Buglife Non-native Land Flatworms guide

Invasive Species Compendium on Obama nungara

Freshwater Flatworm Recording Scheme

Books and monographs

Ball, T. and Reynoldson, T.B. (1983) British Planarians #19 in the Synopses of the British Fauna. Cambridge University Press (Out of print)

Reynoldson, T.B. and Young, J.O. (2000) A Key to the Freshwater Triclads of Britain and Ireland, with Notes on their Ecology. Freshwater Biological Association

Jones, H.D. 2005. Identification: British land flatworms. British Wildlife 16(3): 189-194.

Gibson, R. (1972) Nemerteans. Hutchinson University Library

Page drafted and compiled by Steve Head

Argonemertes dendyi found in leaf litter near Camborne, Cornwall in 2016

Argonemertes dendyi found in leaf litter near Camborne, Cornwall in 2016

Reference:

1. Jones, H.D. 2005. Identification: British land flatworms. British Wildlife 16(3): 189-194.

Other sources of information

Websites

Buglife Non-native Land Flatworms guide

Invasive Species Compendium on Obama nungara

Freshwater Flatworm Recording Scheme

Books and monographs

Ball, T. and Reynoldson, T.B. (1983) British Planarians #19 in the Synopses of the British Fauna. Cambridge University Press (Out of print)

Reynoldson, T.B. and Young, J.O. (2000) A Key to the Freshwater Triclads of Britain and Ireland, with Notes on their Ecology. Freshwater Biological Association

Jones, H.D. 2005. Identification: British land flatworms. British Wildlife 16(3): 189-194.

Gibson, R. (1972) Nemerteans. Hutchinson University Library

Page drafted and compiled by Steve Head