- Home

- Garden Wildlife

- Arthropods

- Crustacea

- Pond crustaceans

Fish louse Argulus folicaeus Fish louse Argulus sp on stickleback

References

1. Holdich, D.M. and Sibley,P.J. (2009) ICS and NICS in Britain in the 2000s pp 13-33 in Crayfish Conservation in the British Isles, Proceedings of conference held in Leeds

2. Holdich, D.M., Palmer,M. and Sibley, P.J. (2009) The indigenous status of Austropotamobius pallipes (Lereboullet) in Britain. pp 1-11 in Crayfish Conservation in the British Isles, Proceedings of conference held in Leeds

3. Gouin N., Grandjean F., PainS., Souty-Grosset C. & Reynolds J. (2003) Origin and colonization history of the white-clawed crayfish, Austropotamobius pallipes, in Ireland. Heredity 91: 70–77

4. Maitland, P. S. 1977. A coded check-list of animals occurring in fresh water in the British Isles, Institute of Terrestrial Ecology, Edinburgh.

5. Ruiz, F., Abad, M., Bodergat, A.M. et al. Freshwater ostracods as environmental tracers. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 10, 1115–1128 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13762-013-0249-5

Other sources of information

Website

Simple guide to freshwater shrimp genera from the Freshwater Biological Association here.

Cladocera Interest Group guest blog

Books

Dobson,M. Pawley,S. Fletcher,M. & Powell, A. (2012) Guide to Freshwater Invertebrates Published by Freshwater Biological Association

Gledhill,T. Sutcliffe,D.W. & Williams, W.D. (1993) British Freshwater Crustacea Malacostraca. A Key with Ecological notes. Freshwater Biological Association Scientific Publications Volume: 52.

Harding, J.P.; Smith, W.A. (1974) A Key to the British Freshwater Cyclopid and Calanoid Copepods with ecological notes. 2nd edition Published by Freshwater Biological Association

Scourfield D.J. and Harding J.P. (1966) A Key to the British Freshwater Cladocera with notes on their ecology. Freshwater Biological Association Scientific Publications Volume: 5, 61pp

Page text drafted and compiled by Steve Head

Pond crustaceans

If you have a garden pond, you will almost certainly have populations of freshwater crustaceans, although they will not be as obvious as the dragonflies and other insects. All are small, and most are very small indeed - with the exception of freshwater crayfish, which are not found in typical garden ponds. There are more than 400 species of freshwater crustaceans in Britain and Ireland, classified in a number of Orders, but many, such as the tadpole shrimp and the fairy shrimp are very rare and only found in temporary ponds. We can only give a taste of their diversity here, but we know so little about crustaceans in garden ponds that it would be great if people did some citizen science and found out what is in their ponds. Full identification to species level is very tricky however.

Crayfish

There are seven introduced species of crayfish living wild in Britain1.Two species are common enough to consider here The supposedly native white-clawed crayfish Austropotamobius pallipes was actually introduced to England a little before 1500AD2,3, making it legally "indigenous" but not native. Populations in Ireland3 represent a second early introduction. Populations in Scotland2 are much more recent introductions. This species is rapidly declining, the principal reason being competition with, and fungal diseases caught from, the invasive North American signal crayfish Pacifastacus leniusculus. Unlike the indigenous species which prefers running water, the signal crayfish can inhabit ponds. This species is now legally prohibited from being bred or released in Europe, and if you have them in your pond you should consider temporarily draining it and removing the crayfish, which are excellent eating!

White-clawed crayfish Austropotamobius pallipes Signal crayfish Pacifastacus leniusculus

Note the white "signal" at the hinge of the claw.

Water slaters Asellidae

Water slaters are isopods, so in the same crustacean group as the woodlice. They are exclusively aquatic and don't swim effectively, preferring to wander around on the pond bottom and on dead leaves vegetation. They feed on debris and algae, and do no harm to other inhabitants. They are tolerant of stagnant muddy water.

The commonest species in Britain and Ireland is the two-spotted water slater Asellus aquaticus, up to 15mm long, with two cream coloured spots on the back of the head. The closely related Asellus meridianus is slightly smaller and the spots coalesce to a band.

_(Waterlouse)_-_(imago),_Elst_(Gld),_the_Netherlands.jpg)

Common water slater Asellus aquaticus, views from above and the side

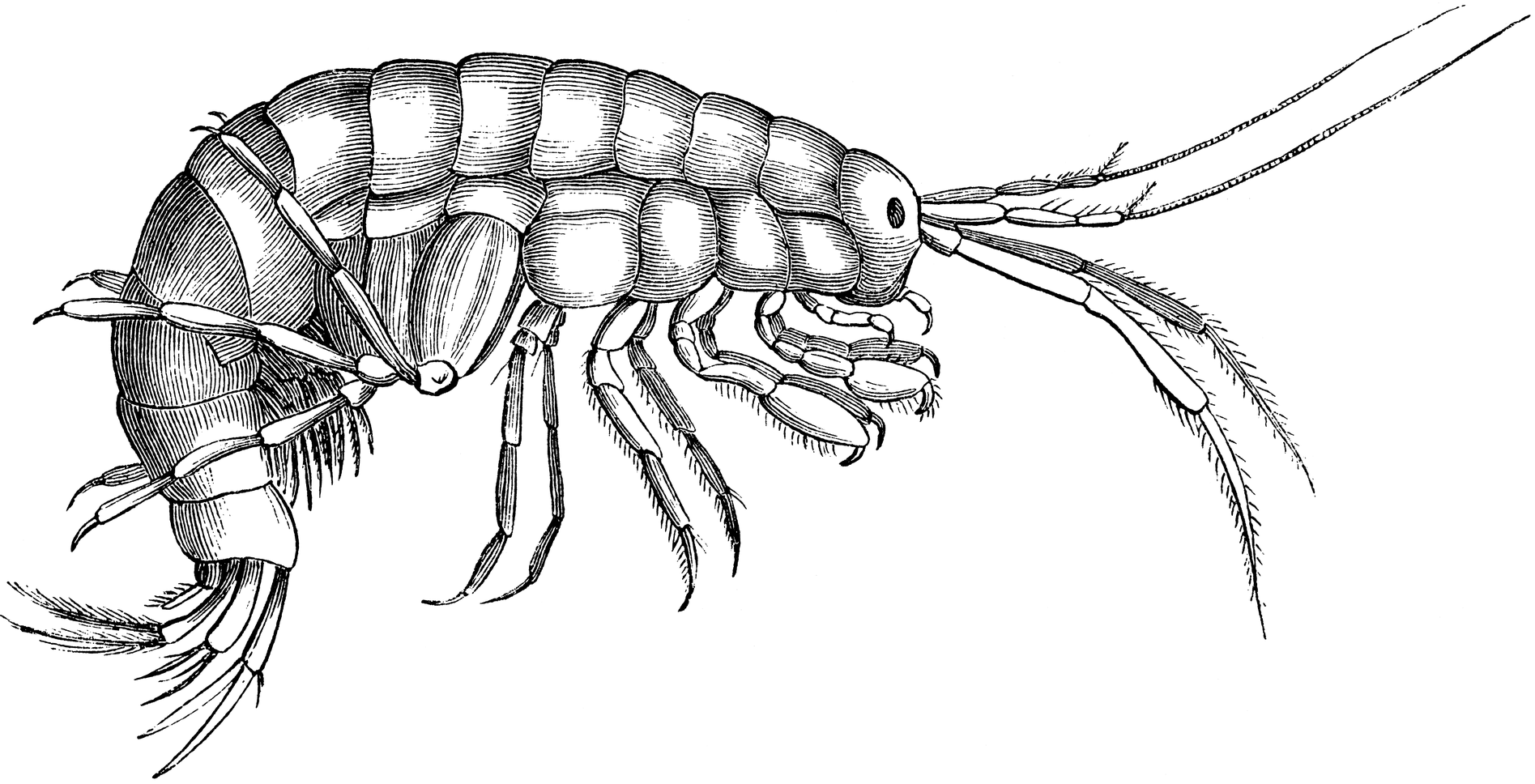

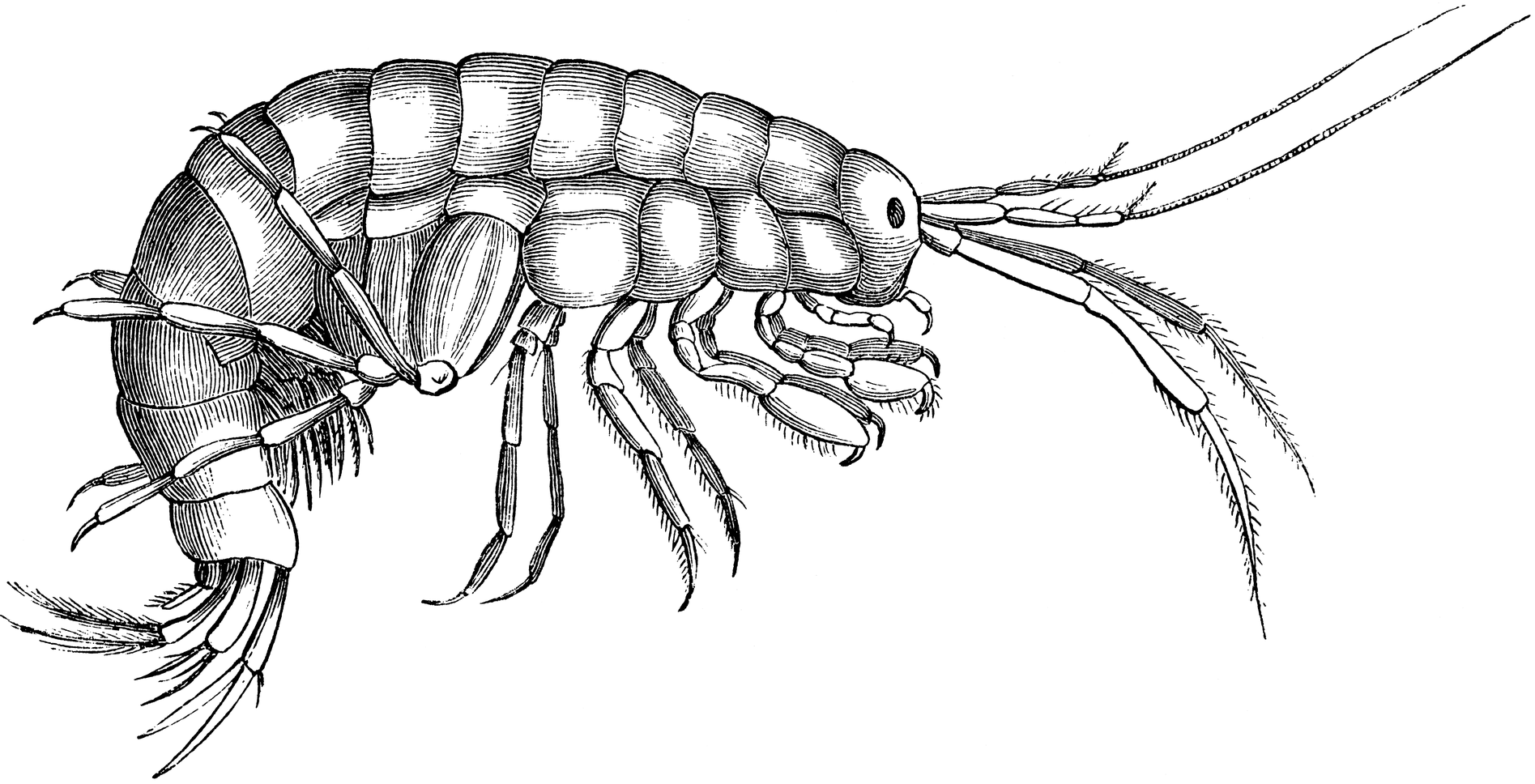

Freshwater shrimps are amphipods, related to the landhopper. There is only one species likely to be found in ponds, and that is Crangonyx pseudogracilis. This is actually an American species, first seen in Britain in 1936, and it has colonised southern England and continues to spread. It is tolerant of still water and low oxygen conditions. The family to which it belongs is most commonly found in caves where they are often blind and colourless. The other common freshwater shrimp is Gammarus pulex, but this needs high oxygen and flowing water, so is not likely to occur in most garden ponds, but might turn up if you have a stream or a spring in your garden.

The two shrimps appear similar, but Crangonyx is smaller (8mm), darker and walks upright. Gammarus is up to about 20mm, lighter in colour, and scoots around on its side.

Gammarus pulex Drawing, and swarm in a German stream. There seem to be no decent portrait photos of freshwater amphopods available!

Water fleas Order Cladocera

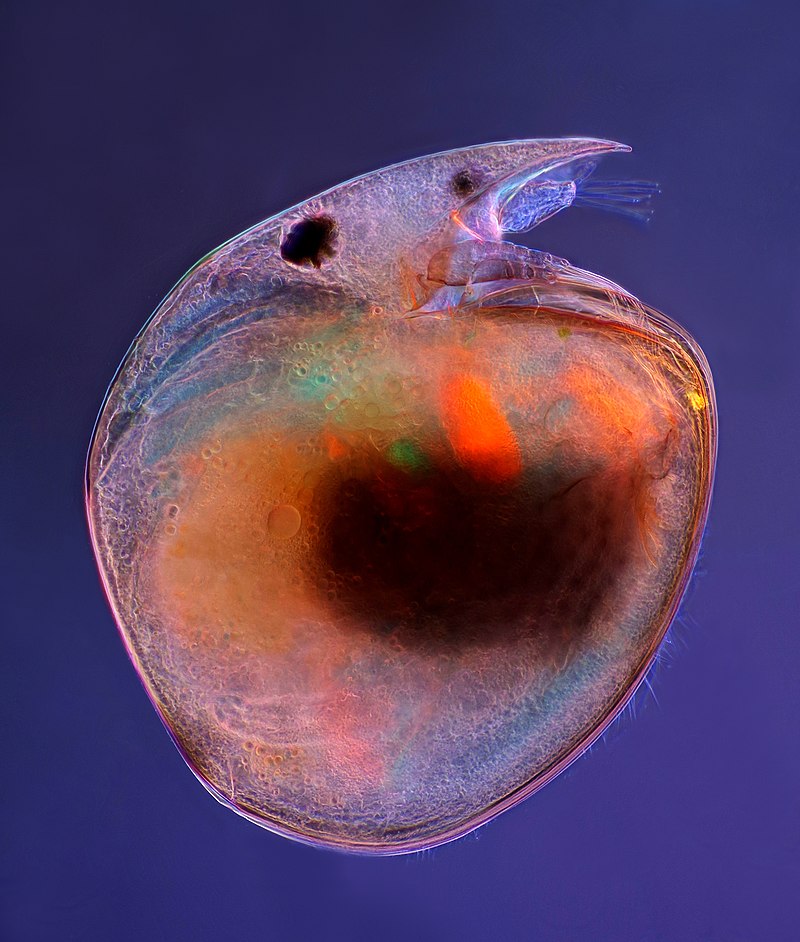

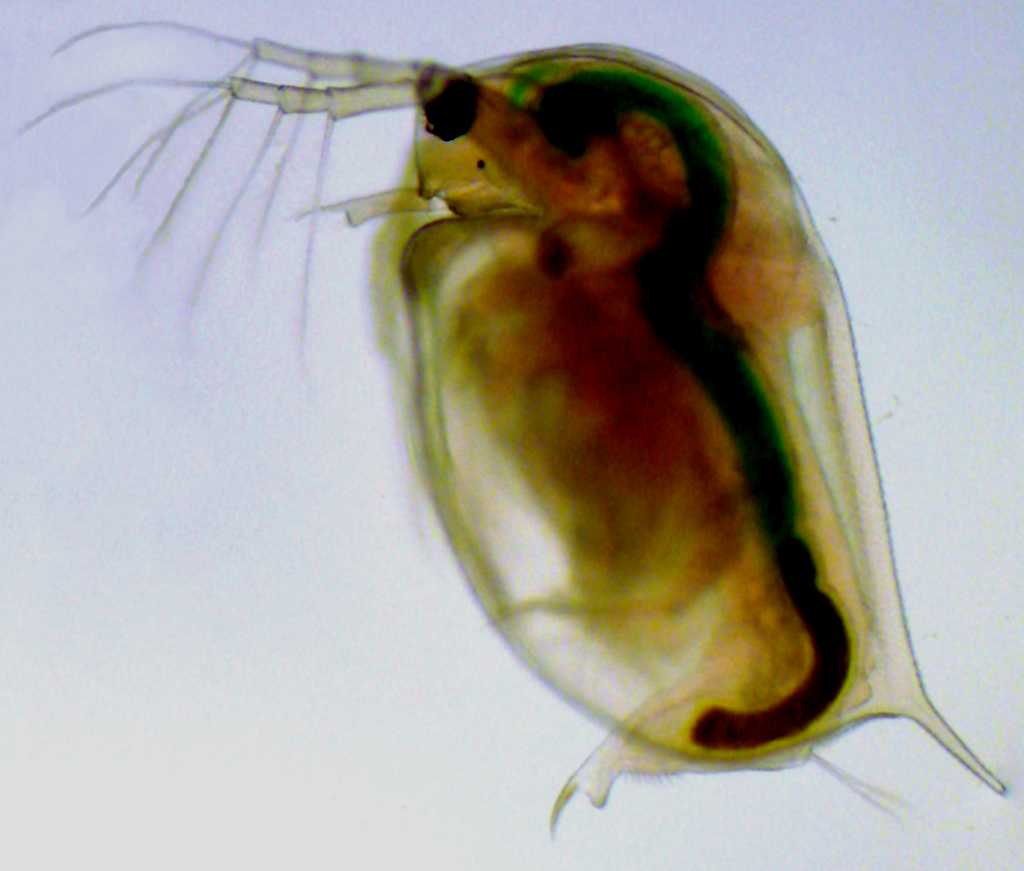

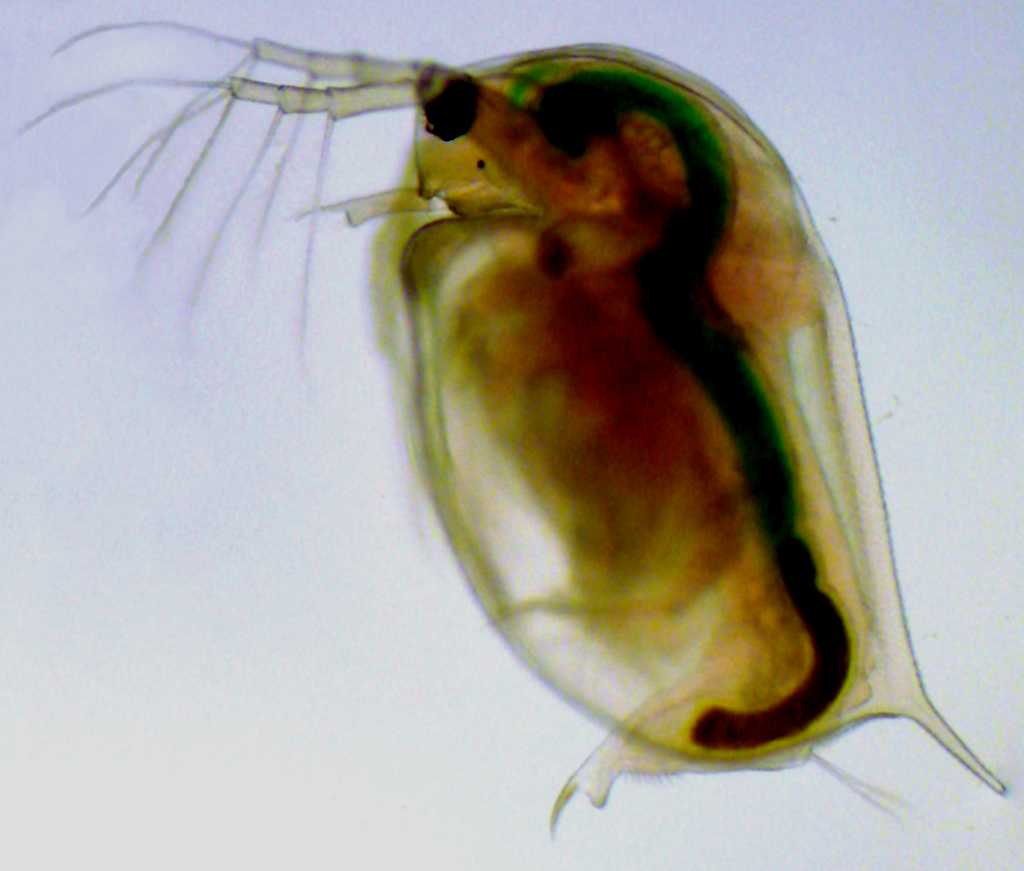

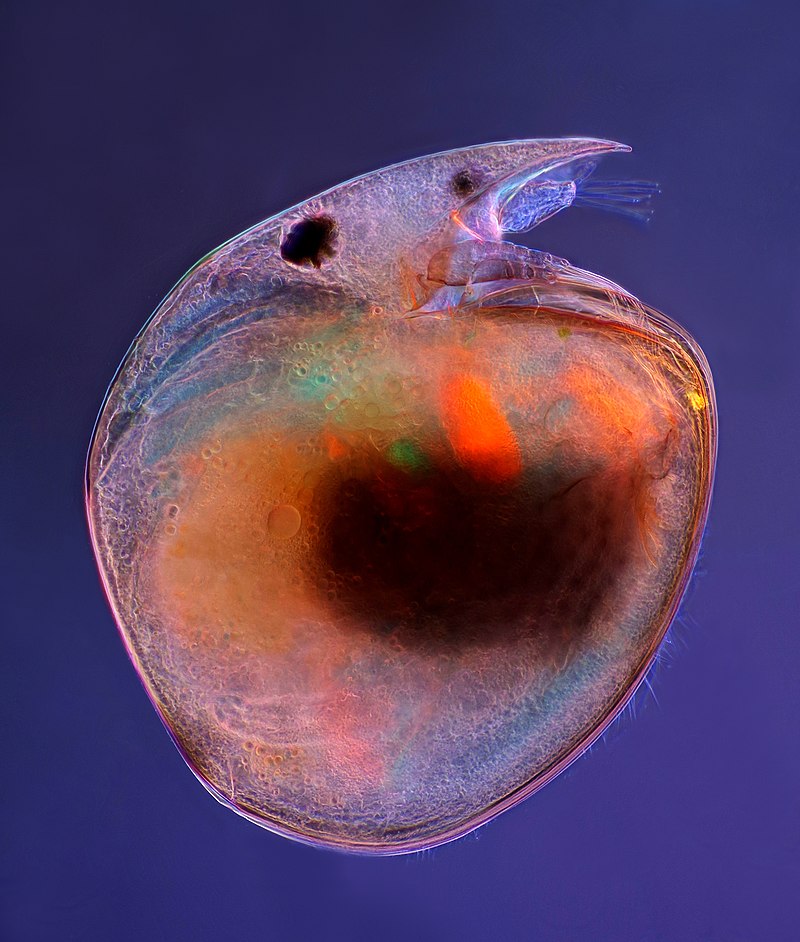

We have over 90 species of water fleas in 8 families in Britain and Ireland. Most are only 0.5 - 4mm long, with a rounded body mostly enclosed in a folded carapace, and a prominent single round eye. They have small limbs used for feeding within the carapace, and a pair of large second antennae which they use to swim in a jery fashion, and which can make them look as if they have their hands up facing a bank robber. They breed parthenogenetically through most of the year, and as winter approaches males appear which fertilise special overwintering embryos held in pouches made by the mother called ephippia. These are highly resistant having been known to survive 700 years in sediment, and can be transported on feathers or in the fur of mammals. Water fleas feed on phytoplankton, detritus and bacteria, and are a very important component in the freshwater food chain, the main food of young dragonflies and small fish. The best known genus is Daphnia with several species. We illustrate only four genera here but they would repay study since we know so little about cladocerans in garden ponds.

Left: female Daphnia pulex with on its "back" a winter-onset ephippium holding overwintering embryos. Above left: the much smaller male, produced only at the end of the year. It has larger first antennae than the female, which can be seen just below the eye.

Above right, female Daphnia longispina with asexual eggs - note the longer spine at the rear of the carapace.

Left to right: Water flea Simocephalus sp. with eggs Very small water flea Chydorus, Water flea Bosmina sp. (large) and Sida crystallina (very small)

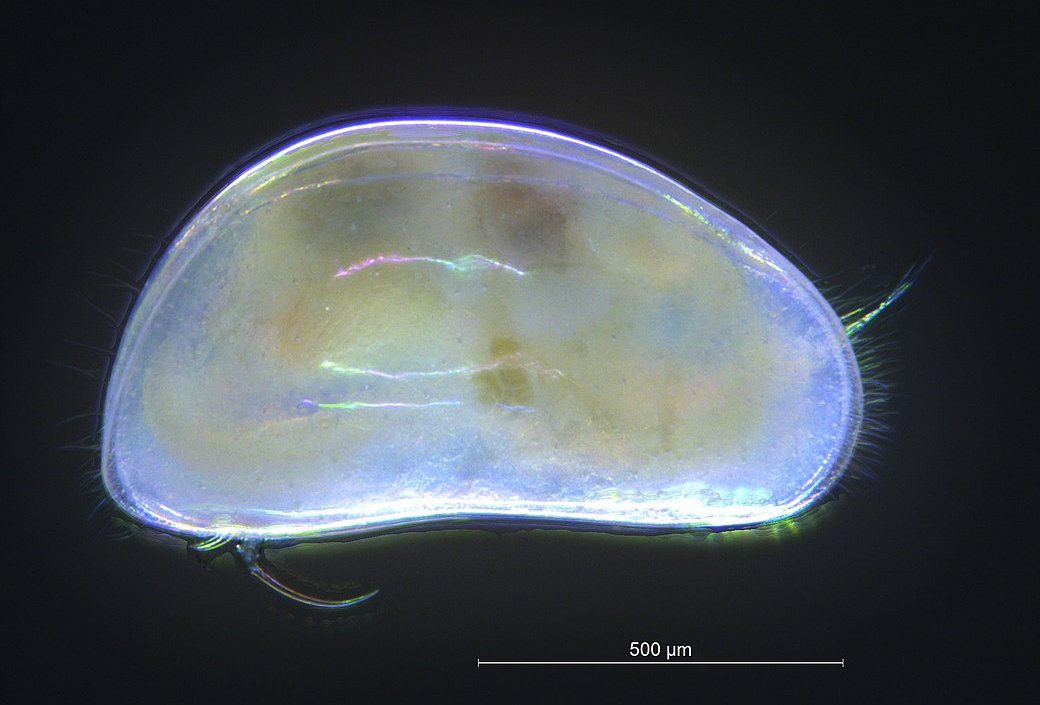

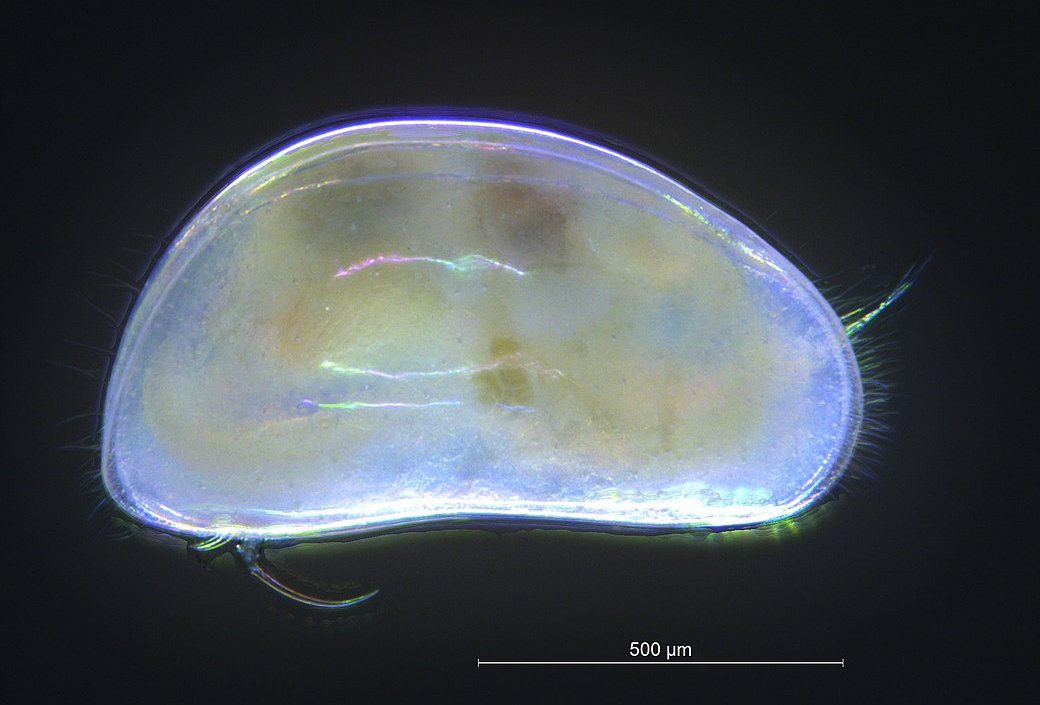

Seed shrimps Ostracoda

This entry is pretty speculative, because we haven't yet found any records of ostracods from garden ponds, but given their abundance in a variety of habitats, it may well be that nobody has really looked for them. It would be great if readers could check their own ponds and see if they can find any. Since writing this page, I have checked my own pond - and - YES! it has lots of ostracods - superficially like Cypria ophthalmica below.

Ostracods are a bit remniscent of cladocerans, but the carapace covers the entire body like the shell of a bivalve, and which can be closed for protection in the same way. Only the large second antennae poke outside the carapce, and the tip of the abdomen. They are very small, mostly less than 2mm in length. They are often found scuttling over vegetation or the substrate, feeding on detritus and plant material. Others swim, but not usually in open water, and feed on plankton. Seed shrimps are common in marine environments too, and are very abundant and important fossils, dating back to the Ordovician period about 400 million years ago.

There are 87 species in Britain and Ireland4. Many freshwater ostracods favour margins of larger water bodies, springs and temporary ponds, but some species are known to tolerate the low oxygen conditions characteristic of smaller ponds. These include Candona candida, Paracyprideis fennica, Cypria opthalmica and Heterocypris incongruens which tolerate temporary low oxygen. Heterocypris sorbyana and Candona neglecta are tolerant of more prolonged low oxygen conditions5.

.png)

Above left: Ostracod Candona candida prominently white in colour.

Above right: Cypria ophthalmica

Left: Unidentified ostracods moving over the bottom of a puddle in a wood in Scotland.

Copepods are another class of very small crustacea (0.25 to 3mm), but they are abundant and extremely important members of marine and freshwater food chains, and may outnumber insects in total population number. Most are planktonic or benthic, and recognised by the long first antennae used for swimming, single midline eye, cylindrical body and forked "tail" When they swim, they move in a jerking fashion as the antennae beat. Other copepods are parasitic on fish and one species the anchor worm Lernaea cyprinacea, may turn up on goldfish if you have them in your pond.

There are two groups of free-living copepods in small ponds. The best known genus is Cyclops (in the Cyclopoidea) which has both planktonic and bottom living species, and is easily recognised by the twin egg-sacs of the female. There are about 100 species in NW Europe, and very hard to tell apart. Copepods in the Order Harpacticoidea do not swim, but move around on plants or the pond bottom. Canthocamptus is a representative genus - there are about 200 species, and we know nothing about their diversity in garden ponds!

Left: Copepod Cyclops female with egg sacs and male with grasping antennae used in mating. Centre: harpacticoid copepod Canthocamptus sp. Right: Parasitic copepod Lernaea cyprinacea - highly modified and worm-like. Note the "anchors" at the head used to hold onto the host.

Fish lice Branchiura

Fish lice are parasites on fish, amphibians and some invertebrates and grow up to 10mm in length. They have a very flattened and saucer-shaped carapace, with four pairs of swiming legs beneath which allows them to swim and move over the surface of their host. They have two prominent eyes, and two large suckers behind the head. They feed on blood and are a common problem for keepers of koi and other fish, and they may also occur in ordinary ponds with or without fish - but we know little of them in garden ponds. The commonest species is Argulus foliaceus.

.jpg)

Pond crustaceans

If you have a garden pond, you will almost certainly have populations of freshwater crustaceans, although they will not be as obvious as the dragonflies and other insects. All are small, and most are very small indeed - with the exception of freshwater crayfish, which are not found in typical garden ponds. There are more than 400 species of freshwater crustaceans in Britain and Ireland, classified in a number of Orders, but many, such as the tadpole shrimp and the fairy shrimp are very rare and only found in temporary ponds. We can only give a taste of their diversity here, but we know so little about crustaceans in garden ponds that it would be great if people did some citizen science and found out what is in their ponds. Full identification to species level is very tricky however.

Crayfish

There are seven introduced species of crayfish living wild in Britain1.Two species are common enough to consider here The supposedly native white-clawed crayfish Austropotamobius pallipes was actually introduced to England a little before 1500AD2,3, making it legally "indigenous" but not native. Populations in Ireland3 represent a second early introduction. Populations in Scotland2 are much more recent introductions. This species is rapidly declining, the principal reason being competition with, and fungal diseases caught from, the invasive North American signal crayfish Pacifastacus leniusculus. Unlike the indigenous species which prefers running water, the signal crayfish can inhabit ponds. This species is now legally prohibited from being bred or released in Europe, and if you have them in your pond you should consider temporarily draining it and removing the crayfish, which are excellent eating!

Left: white-clawed crayfish Austropotamobius pallipes Right: Signal crayfish Pacifastacus leniusculus Note the white "signal" at the hinge of the claw.

Water slaters Asellidae

Water slaters are isopods, so in the same crustacean group as the woodlice. They are exclusively aquatic and don't swim effectively, preferring to wander around on the pond bottom and on dead leaves vegetation. They feed on debris and algae, and do no harm to other inhabitants. They are tolerant of stagnant muddy water.

The commonest species in Britain and Ireland is the two-spotted water slater Asellus aquaticus, up to 15mm long, with two cream coloured spots on the back of the head. The closely related Asellus meridianus is slightly smaller and the spots coalesce to a band.

_(Waterlouse)_-_(imago),_Elst_(Gld),_the_Netherlands.jpg)

Common water slater Asellus aquaticus, views from above and the side

Freshwater shrimps are amphipods, related to the landhopper. There is only one species likely to be found in ponds, and that is Crangonyx pseudogracilis. This is actually an American species, first seen in Britain in 1936, and it has colonised southern England and continues to spread. It is tolerant of still water and low oxygen conditions. The family to which it belongs is most commonly found in caves where they are often blind and colourless. The other common freshwater shrimp is Gammarus pulex, but this needs high oxygen and flowing water, so is not likely to occur in most garden ponds, but might turn up if you have a stream or a spring in your garden.

The two shrimps appear similar, but Crangonyx is smaller (8mm), darker and walks upright. Gammarus is up to about 20mm, lighter in colour, and scoots around on its side.

Gammarus pulex Drawing, and swarm in a German stream. There seem to be no decent portrait photos of freshwater amphopods available!

We have over 90 species of water fleas in 8 families in Britain and Ireland. Most are only 0.5 - 4mm long, with a rounded body mostly enclosed in a folded carapace, and a prominent single round eye. They have small limbs used for feeding within the carapace, and a pair of large second antennae which they use to swim in a jery fashion, and which can make them look as if they have their hands up facing a bank robber. They breed parthenogenetically through most of the year, and as winter approaches males appear which fertilise special overwintering embryos held in pouches made by the mother called ephippia. These are highly resistant having been known to survive 700 years in sediment, and can be transported on feathers or in the fur of mammals. Water fleas feed on phytoplankton, detritus and bacteria, and are a very important component in the freshwater food chain, the main food of young dragonflies and small fish. The best known genus is Daphnia with several species. We illustrate only four genera here but they would repay study since we know so little about cladocerans in garden ponds.

Left: female Daphnia pulex with on its "back" a winter-onset ephippium holding overwintering embryos. centret: the much smaller male, produced only at the end of the year. It has larger first antennae than the female, which can be seen just below the eye.

Above right, female Daphnia longispina with asexual eggs - note the longer spine at the rear of the carapace.

Left to right: Water flea Simocephalus sp. with eggs Very small water flea Chydorus, Water flea Bosmina sp. (large) and Sida crystallina (very small)

Seed shrimps Ostracoda

This entry is pretty speculative, because we haven't yet found any records of ostracods from garden ponds, but given their abundance in a variety of habitats, it may well be that nobody has really looked for them. It would be great if readers could check their own ponds and see if they can find any. Since writing this page, I have checked my own pond - and - YES! it has lots of ostracods - superficially like Cypria ophthalmica below.

Ostracods are a bit remniscent of cladocerans, but the carapace covers the entire body like the shell of a bivalve, and which can be closed for protection in the same way. Only the large second antennae poke outside the carapce, and the tip of the abdomen. They are very small, mostly less than 2mm in length. They are often found scuttling over vegetation or the substrate, feeding on detritus and plant material. Others swim, but not usually in open water, and feed on plankton. Seed shrimps are common in marine environments too, and are very abundant and important fossils, dating back to the Ordovician period about 400 million years ago.

There are 87 species in Britain and Ireland4. Many freshwater ostracods favour margins of larger water bodies, springs and temporary ponds, but some species are known to tolerate the low oxygen conditions characteristic of smaller ponds. These include Candona candida, Paracyprideis fennica, Cypria opthalmica and Heterocypris incongruens which tolerate temporary low oxygen. Heterocypris sorbyana and Candona neglecta are tolerant of more prolonged low oxygen conditions5.

.png)

Above left: Ostracod Candona candida prominently white in colour.

Above right: Cypria ophthalmica

Left: Unidentified ostracods moving over the bottom of a puddle in a wood in Scotland.

Copepods are another class of very small crustacea (0.25 to 3mm), but they are abundant and extremely important members of marine and freshwater food chains, and may outnumber insects in total population number. Most are planktonic or benthic, and recognised by the long first antennae used for swimming, single midline eye, cylindrical body and forked "tail" When they swim, they move in a jerking fashion as the antennae beat. Other copepods are parasitic on fish and one species the anchor worm Lernaea cyprinacea, may turn up on goldfish if you have them in your pond.

There are two groups of free-living copepods in small ponds. The best known genus is Cyclops (in the Cyclopoidea) which has both planktonic and bottom living species, and is easily recognised by the twin egg-sacs of the female. There are about 100 species in NW Europe, and very hard to tell apart. Copepods in the Order Harpacticoidea do not swim, but move around on plants or the pond bottom. Canthocamptus is a representative genus - there are about 200 species, and we know nothing about their diversity in garden ponds!

Left: Copepod Cyclops female with egg sacs and male with grasping antennae used in mating. Centre: harpacticoid copepod Canthocamptus sp. Right: Parasitic copepod Lernaea cyprinacea - highly modified and worm-like. Note the "anchors" at the head used to hold onto the host.

Fish lice Branchiura

Fish lice are parasites on fish, amphibians and some invertebrates and grow up to 10mm in length. They have a very flattened and saucer-shaped carapace, with four pairs of swiming legs beneath which allows them to swim and move over the surface of their host. They have two prominent eyes, and two large suckers behind the head. They feed on blood and are a common problem for keepers of koi and other fish, and they may also occur in ordinary ponds with or without fish - but we know little of them in garden ponds. The commonest species is Argulus foliaceus.

.jpg)

Fish louse Argulus folicaeus Fish louse Argulus sp on stickleback

References

1. Holdich, D.M. and Sibley,P.J. (2009) ICS and NICS in Britain in the 2000s pp 13-33 in Crayfish Conservation in the British Isles, Proceedings of conference held in Leeds

2. Holdich, D.M., Palmer,M. and Sibley, P.J. (2009) The indigenous status of Austropotamobius pallipes (Lereboullet) in Britain. pp 1-11 in Crayfish Conservation in the British Isles, Proceedings of conference held in Leeds

3. Gouin N., Grandjean F., PainS., Souty-Grosset C. & Reynolds J. (2003) Origin and colonization history of the white-clawed crayfish, Austropotamobius pallipes, in Ireland. Heredity 91: 70–77

4. Maitland, P. S. 1977. A coded check-list of animals occurring in fresh water in the British Isles, Institute of Terrestrial Ecology, Edinburgh.

5. Ruiz, F., Abad, M., Bodergat, A.M. et al. Freshwater ostracods as environmental tracers. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 10, 1115–1128 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13762-013-0249-5

Other sources of information

Website

Cladocera Interest Group guest blog

Books

Dobson,M. Pawley,S. Fletcher,M. & Powell, A. (2012) Guide to Freshwater Invertebrates Published by Freshwater Biological Association

Gledhill,T. Sutcliffe,D.W. & Williams, W.D. (1993) British Freshwater Crustacea Malacostraca. A Key with Ecological notes. Freshwater Biological Association Scientific Publications Volume: 52.

Harding, J.P.; Smith, W.A. (1974) A Key to the British Freshwater Cyclopid and Calanoid Copepods with ecological notes. 2nd edition Published by Freshwater Biological Association

Scourfield D.J. and Harding J.P. (1966) A Key to the British Freshwater Cladocera with notes on their ecology. Freshwater Biological Association Scientific Publications Volume: 5, 61pp

Page text drafted and compiled by Steve Head