_(14443845696).jpg)

Garden Wildlife

Garden Wildlife

Garden Gnomes

Early evolution of garden gnomes

Garden gnomes are not native to Britain and Ireland, but evolved comparatively recently in post-glacial Europe. They first came to note in the drawings of the French printmaker Jacques Callot (1592-1635). In 1616 he created a series of 21 etchings of "Grotesque Dwarves" which he called "Gobbi", which is an Italian term for hunchback.

Frontispiece of Callot's Gobbi prints. Callot's violin player

The classic German garden gnome was male, bearded, wearing a red pointy hat, and frequently in a reclining posture, smoking a pipe.

Colonisation of British and Irish gardens

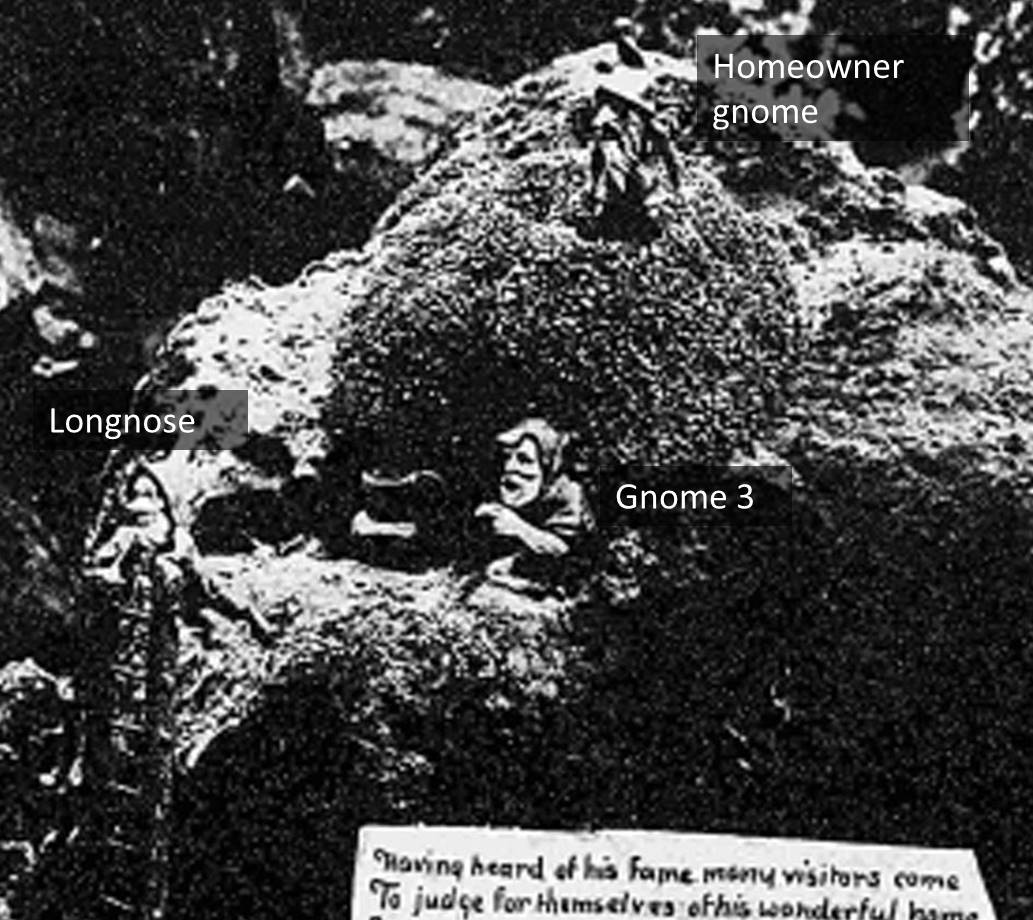

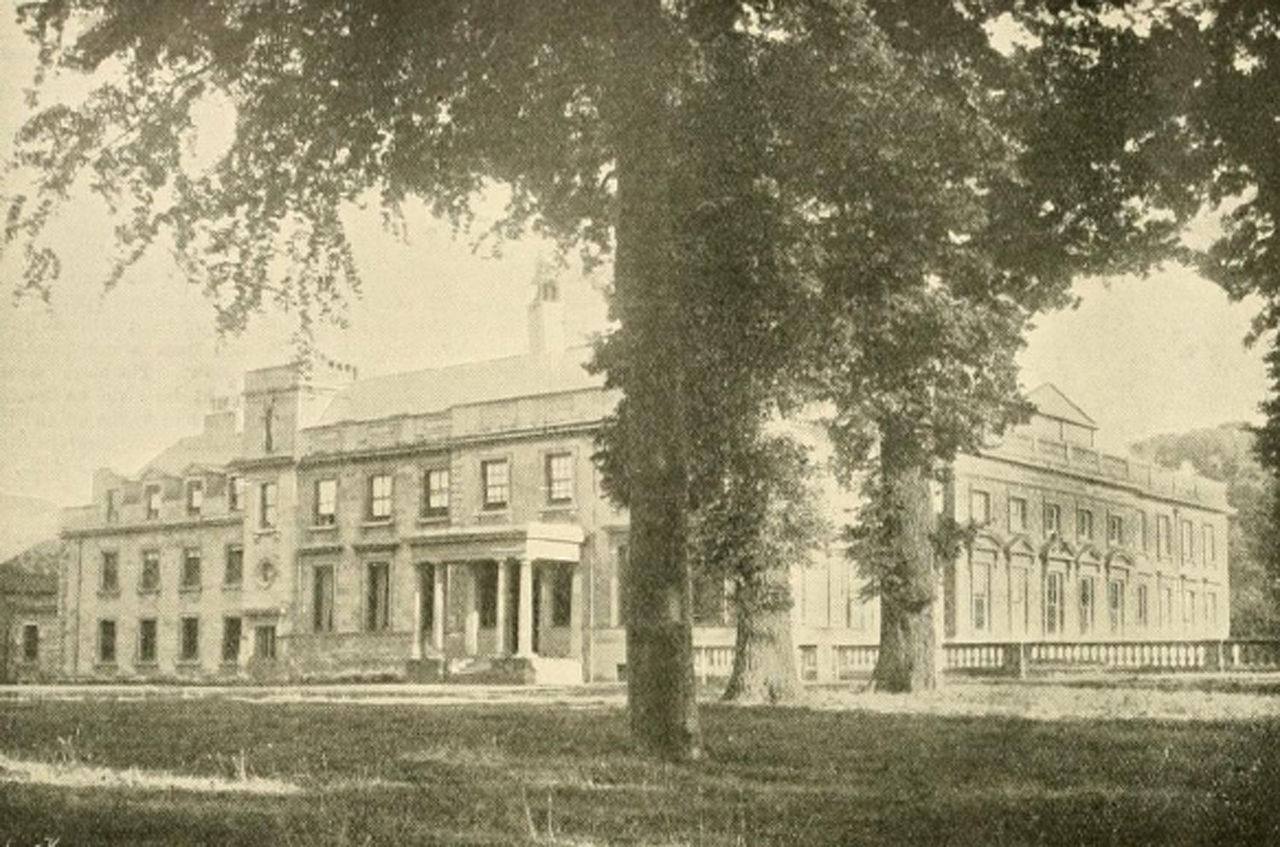

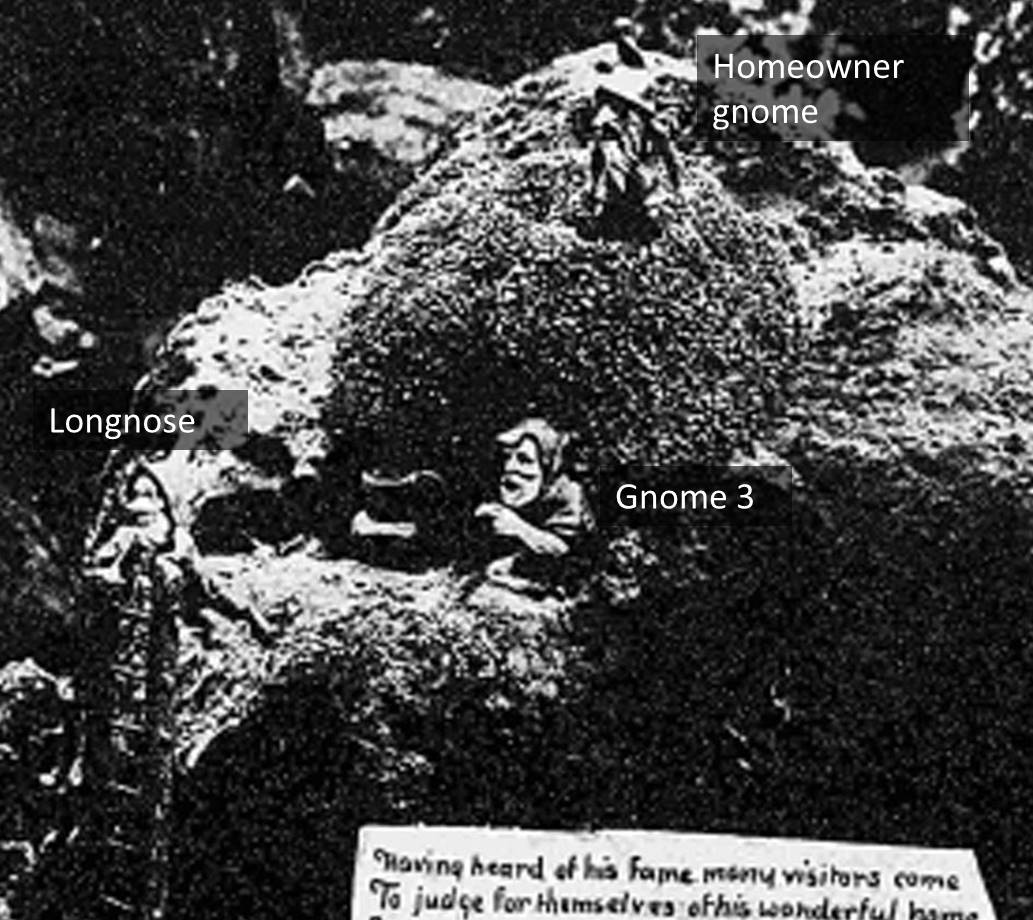

This can be pinpointed unusually accurately to 1874. From 1847, Sir Charles Isham, a Northamptonshire landowner and gardener constructed an exceptionally large rockery feature in his garden at Lamport Hall. In 1874 he imported 21 terracotta gartenzwerge made by Philip Griebel, and placed them in set-piece tableaux around the rockery, often with explanatory poems. After Sir Charles' death in 1903, the gnomes were not prized by his descendants, and now only one, nicknamed "Lampy" remains, allegedly insured for one million pounds.

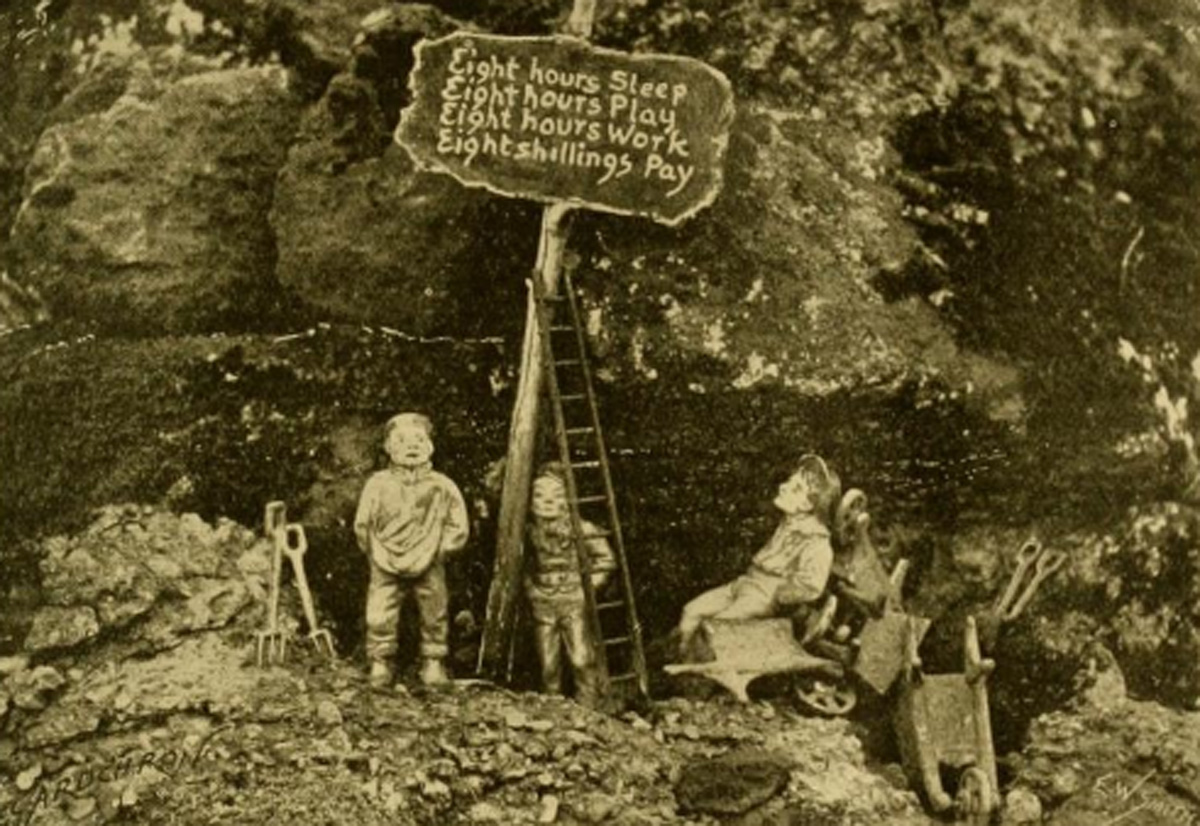

Lamport Hall in 1898 Sir Charles Isham walking in the grounds in 1898

The gnome rockery at Lamport Hall Replica of "Lampy", Lamport's last surviving gnome

Full text below these three gnomes:

Having heard of his fame many visitors come

To judge for themselves of his wonderful home.

Just now there are two, he's too kind to complain

Yet he doubtless alone would prefer to remain.

The one is all active, the other looks on

Whilst owner is wishing them both to be gone.

If Longnose don't mind with his lumbering ladder,

He'll soon come to grief. Now what could be sadder?

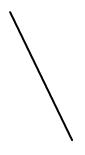

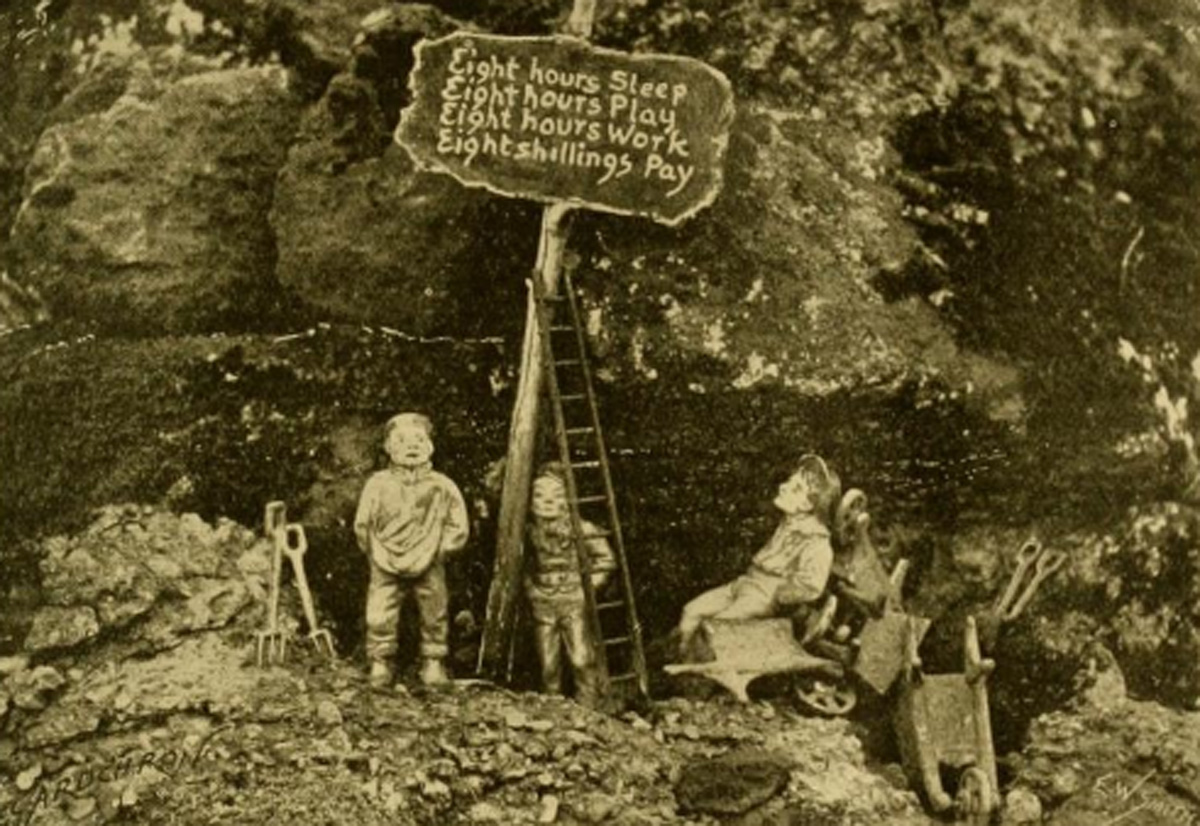

"Gnomes on Strike" The sign reads:

Eight hours Sleep

Eight hours Play

Eight hours Work

Eight shillings Pay

Conservation status

Garden gnomes are not yet listed in the IUCN Red Data Book, and in some countries it would appear that they are flourishing. It has been estimated that the German population of gartenzwerge is of the order of 25 million, nearly twice as many as pet cats, and approaching one for every three humans.

In Britain and Ireland however, the population of garden gnomes is estimated at only 5 million and recruitment to the national population has fallen by 50% since 2006, raising talk of endangered species status and potential local extinction. The decline would appear to be due to hostility on the part of the gardens' human owners, some 94% of a recent sample saying gnomes were "naff" and they would never allow one in their garden. This is despite the RHS allowing two gnomes to appear at the 2013 centenary Chelsea Flower Show. Like many aspects of gardening, fashion is the key, and it is to be hoped that gardeners will come round to welcoming garden gnomes again in due course.

Britain's first gnome reserve has opened within 4 acres near Bideford in Devon. There is an international NGO which specialises in giving gnomes the opportunity of study trips overseas.

Garden-scale conservation projects are quite common, the photo below is of one which has created a whole ecosystem in Dunster within Exmoor National Park.

Species in Britain and Ireland

The taxonomy of garden gnomes is in a state of hopeless disarray. They all appear to be humanoid primates, but the wide diversity of size and activity leads to suspicion that several species may be involved. Certainly the earlier gnomes had an almost exclusively silicon-based (ceramic) body plan, although rare cellulose and lignin-based (wooden) gnomes were recorded. In recent years the majority of gnomes have been grown from complex long-chain organic materials (plastic).

It may be that all gnomes are of a single but very variable species, with some regional diversity. We have mentioned the classic German gnome, some Irish gnomes are also distinctive, with green tall hats and shamrocks, suggesting interbreeding with leprachauns. No DNA studies have yet been conducted to resolve this impasse.

Biology and life cycle of garden gnomes

It is assumed that, like humans, gnomes are essentially omnivorous. Some are encountered with spades or rakes, engaged in vegetable production, while fishing gnomes were once a common site.

For many years the life cycle of gnomes was very unclear. Garden gnomes were invariably male, and their long white beards suggested they were old and largely at the end of their reproductive life. There was no evidence of immature or juvenile gnomes, and especially no sightings of female gnomes. It was generally assumed that such goings-on took place in private, and probably in underground dwellings.

More recently, demonstrably female garden gnomes have been seen in gardens, suggesting the process of emancipation among gnomes has followed, with some time delay, that of female humans in society.

Female gnomes. Left a teenage female gnome. Right a family of gnomes. This photograph provides some of the first evidence that male gnomes are born with long white beards and big noses, so the old gnomes of many earlier records may in fact have been younger than realised at the time.

Role of gnomes in gardens

There is little evidence of any negative impact gnomes have on other garden biodiversity. No cases have been reported of traditional fishing gnomes actually catching any fish. On the positive side, larger gnomes left undisturbed in situ can provide useful shelter underneath for small invertebrates, notably spiders and woodlice. In recent years some worrying trends have occurred, with gnomes showing anti-social behaviour, especially "mooning" or "flashing" at visitors, riding powerful motor-bikes, pretending to be zombies and practicing at being urban guerillas.

![Censored from: Photo by Norbert Kaiser [CC BY-SA 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5)]](images/censored.jpg)

Reference

1. Entry for "Gnome" Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (2002)

Other sources of information

Website

Wikipedia Garden Gnomes

Garden Gnome Liberation Front

Gnome Conservation Society (Italian)

Books

Wil Huygen (1977) Gnomes (originally in Dutch as "Leven en werken van de kabouter")

Web page drafted and edited by an anonymous Gartenzwerge in Oxfordshire

Callot's caricatures were widely circulated, and in England inspired several porcelain factories to create small novelty figures called "Grotesque Dwarves" or "Mansion House Dwarves". This image is of a Chelsea Porcelain factory example made between 1750 and 1752.

Meanwhile, in Switzerland and Germany, wooden and ceramic (respectively) statuettes were made during the nineteenth century, and these garden novelties were linked with traditional folk lore stories of "little folk". The German name for these gnomes is "Gartenzwerge". Baehr and Maresch of Dresden had them in stock in 1841.

It has been suggested that the word "gnome" in English came from the catalogue description of their products as "Gnomen-Figuren" (miniature figurines), but the word first was recorded in English in 1630-16691.

Garden Gnomes

Early evolution of garden gnomes

Garden gnomes are not native to Britain and Ireland, but evolved comparatively recently in post-glacial Europe. They first came to note in the drawings of the French printmaker Jacques Callot (1592-1635). In 1616 he created a series of 21 etchings of "Grotesque Dwarves" which he called "Gobbi", which is an Italian term for hunchback.

Frontispiece of Callot's Gobbi prints. Callot's violin player

Callot's caricatures were widely circulated, and in England inspired several porcelain factories to create small novelty figures called "Grotesque Dwarves" or "Mansion House Dwarves". This image is of a Chelsea Porcelain factory example made between 1750 and 1752.

Meanwhile, in Switzerland and Germany, wooden and ceramic (respectively) statuettes were made during the nineteenth century, and these garden novelties were linked with traditional folk lore stories of "little folk". The German name for these gnomes is "Gartenzwerge". Baehr and Maresch of Dresden had them in stock in 1841.

It has been suggested that the word "gnome" in English came from the catalogue description of their products as "Gnomen-Figuren" (miniature figurines), but the word first was recorded in English in 1630-16691.

The classic German garden gnome was male, bearded, wearing a red pointy hat, and frequently in a reclining posture, smoking a pipe.

Colonisation of British and Irish gardens

This can be pinpointed unusually accurately to 1874. From 1847, Sir Charles Isham, a Northamptonshire landowner and gardener constructed an exceptionally large rockery feature in his garden at Lamport Hall. In 1874 he imported 21 terracotta gartenzwerge made by Philip Griebel, and placed them in set-piece tableaux around the rockery, often with explanatory poems. After Sir Charles' death in 1903, the gnomes were not prized by his descendants, and now only one, nicknamed "Lampy" remains, allegedly insured for one million pounds.

Lamport Hall in 1898 Sir Charles Isham walking in the grounds in 1898

The gnome rockery at Lamport Hall Replica of "Lampy", Lamport's last

surviving gnome

"Gnomes on Strike" The sign reads:

Eight hours Sleep

Eight hours Play

Eight hours Work

Eight shillings Pay

Original text below these three gnomes:

Having heard of his fame many visitors come

To judge for themselves of his wonderful home.

Just now there are two, he's too kind to complain

Yet he doubtless alone would prefer to remain.

The one is all active, the other looks on

Whilst owner is wishing them both to be gone.

If Longnose don't mind with his lumbering ladder,

He'll soon come to grief. Now what could be sadder?

Species in Britain and Ireland

The taxonomy of garden gnomes is in a state of hopeless disarray. They all appear to be humanoid primates, but the wide diversity of size and activity leads to suspicion that several species may be involved. Certainly the earlier gnomes had an almost exclusively silicon-based (ceramic) body plan, although rare cellulose and lignin-based (wooden) gnomes were recorded. In recent years the majority of gnomes have been grown from complex long-chain organic materials (plastic).

It may be that all gnomes are of a single but very variable species, with some regional diversity. We have mentioned the classic German gnome, some Irish gnomes are also distinctive, with green tall hats and shamrocks, suggesting interbreeding with leprachauns. No DNA studies have yet been conducted to resolve this impasse.

Biology and life cycle of garden gnomes

It is assumed that, like humans, gnomes are essentially omnivorous. Some are encountered with spades or rakes, engaged in vegetable production, while fishing gnomes were once a common site.

For many years the life cycle of gnomes was very unclear. Garden gnomes were invariably male, and their long white beards suggested they were old and largely at the end of their reproductive life. There was no evidence of immature or juvenile gnomes, and especially no sightings of female gnomes. It was generally assumed that such goings-on took place in private, and probably in underground dwellings.

More recently, demonstrably female garden gnomes have been seen in gardens, suggesting the process of emancipation among gnomes has followed, with some time delay, that of female humans in society.

![Censored from: Photo by Norbert Kaiser [CC BY-SA 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5)]](images/censored.jpg)

_(14443845696).jpg)

Female gnomes. Left a teenage female gnome. Right a family of gnomes. This photograph provides some of the first evidence that male gnomes are born with long white beards and big noses, so the old gnomes of many earlier records may in fact have been younger than realised at the time.

Role of gnomes in gardens

There is little evidence of any negative impact gnomes have on other garden biodiversity. No cases have been reported of traditional fishing gnomes actually catching any fish. On the positive side, larger gnomes left undisturbed in situ can provide useful shelter underneath for small invertebrates, notably spiders and woodlice. In recent years some worrying trends have occurred, with gnomes showing anti-social behaviour, especially "mooning" or "flashing" at visitors, riding powerful motor-bikes, pretending to be zombies and practicing at being urban guerillas.

Conservation status

Garden gnomes are not yet listed in the IUCN Red Data Book, and in some countries it would appear that they are flourishing. It has been estimated that the German population of gartenzwerge is of the order of 25 million, nearly twice as many as pet cats, and approaching one for every three humans.

In Britain and Ireland however, the population of garden gnomes is estimated at only 5 million and recruitment to the national population has fallen by 50% since 2006, raising talk of endangered species status and potential local extinction. The decline would appear to be due to hostility on the part of the gardens' human owners, some 94% of a recent sample saying gnomes were "naff" and they would never allow one in their garden. This is despite the RHS allowing two gnomes to appear at the 2013 centenary Chelsea Flower Show. Like many aspects of gardening, fashion is the key, and it is to be hoped that gardeners will come round to welcoming garden gnomes again in due course.

Britain's first gnome reserve has opened within 4 acres near Bideford in Devon. There is an international NGO which specialises in giving gnomes the opportunity of study trips overseas.

Garden-scale conservation projects are quite common, the photo below is of one which has created a whole ecosystem in Dunster within Exmoor National Park.

Reference

1. Entry for "Gnome" Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (2002)

Other sources of information

Website

Wikipedia Garden Gnomes

Garden Gnome Liberation Front

Books

Wil Huygen (1977) Gnomes (originally in Dutch as "Leven en werken van de kabouter")

Web page drafted and edited by an anonymous Gartenzwerge in Oxfordshire